3017

Changes in brain pulsatility associated with heart rate elevation using amplified MRI and phase-contrast MRI1GE Healthcare, Gisborne, New Zealand, 2Auckland Bioengineering Institute, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 3Mātai Medical Research Institute, Gisborne, New Zealand, 4University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 5Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences & Centre for Brain Research, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 6Ngai Tāmanuhiri, Rongowhakaata, Ngāti Porou, Tūranganui-a-Kiwa, Tūranganui-a-Kiwa, Tairāwhiti, New Zealand, 7Sports Performance Research Institute New Zealand, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Neuroscience, Brain motion, image analysis

Cardiac pulsatility is a key driver of brain pulsatility. However, changes in brain pulsatility in response to changes in heart rate have been sparsely studied. Using a combination of amplified MRI and phase-contrast MRI, brain parenchyma motion, blood flow, and CSF flow were measured and assessed during rhythmic hand-grip exercise to help understand the role of heart rate on brain physiology. This approach opens opportunities for probing the role of heart rate, brain fluid, and motion flow in various pathologies that affect the brain.INTRODUCTION

Cardiac pulsatility is a key driver of brain pulsatility [1-6]. Cardiac-gated phase-contrast (PC-MRI) acquisitions are regularly applied for measuring cerebrovascular (blood) and cerebrospinal (CSF) flow. Additionally, brain motion and pulsation have been studied recently using a technique called amplified MRI (aMRI) [7-9]. Heart rate is fundamental to these acquisitions. Studying effects of changes in heart rate during natural (i.e. due to caffeine consumption) and induced elevations (i.e. physical exercise) allows investigation and interpretation of inter- and intra- subject variabilities. Despite these important considerations, changes in brain pulsatility in response to elevations in heart rate have been sparsely studied. In this work, we measured brain motion using 3D aMRI [8-9], and blood and CSF flow using PC-MRI [1-2,10], to help understand the role of heart rate elevation in brain physiology.Methods

Study design: A rhythmic hand grip exercise (RHG) [1] was employed as physiological load to investigate brain pulsatility at elevated heart rates. Participants underwent MRI scanning in a randomized cross-over design between lying supine and RHG conditions with a 15-minute break between conditions. Participants abstained from caffeine consumption and strenuous exercise prior to scan. During RHG, participants continuously squeezed and released a silicone ring (at a cadence of 2:2 seconds) corresponding to 40% of their maximum grip strength for ten minutes. The RHG condition was intended to raise heart rate to a steady state ~10 beats per minute above the resting condition.MRI acquisition: Under ethics approval, 6 healthy adults (4 Female/2 Male) underwent MRI scanning at baseline and during RHG. All scans were acquired on a 3T MRI scanner (GE SIGNA Premier; General Electric, MI, USA; AIRTM 48-channel head coil). Three scans were acquired:

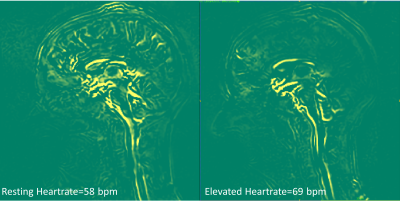

- Brain motion: cine 3D bSSFP [11,12] (the base acquisition for aMRI, 20 cardiac phases, near isotropic resolution of 1.0x1.0x1.3mm, 116 slices, 2:30min scan).

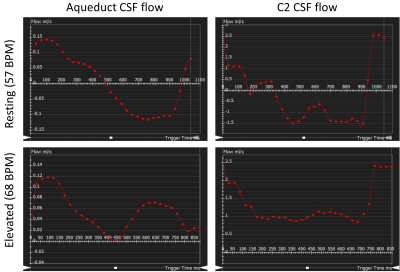

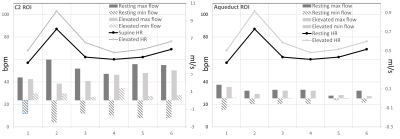

- CSF flow: single-slice 2D cine PC-MRI positioned perpendicular to the direction of flow at the aqueduct of Sylvius and at the level of the C2/C3 subarachnoid space (venc = 9cm/s, 30 cardiac phases, resolution 0.7x0.7x5mm,1.4 px/mm).

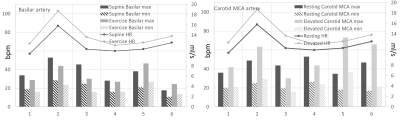

- Blood flow: 4D PC-MRI (venc=80 cm/s, 20 cardiac phases, resolution 0.86x0.86x1.5 mm, 2:07 min scan time).

Results

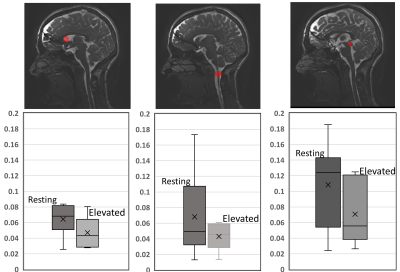

Overall, with an elevated heart rate, a decrease in CSF maximum flow was observed at the C2 and aqueduct locations (Figs. 1-2). Also, CSF flow was positive during systole and diastole. Deceleration of CSF flow was observed but there was no regurgitation like those seen in the resting heart rate measurements. Except for subject 4, all subjects showed (Fig. 3) an increase in carotid MCA net flow and a decrease in venous net flow with elevated heart rate. Subjects 1 to 4 showed a decrease in basilar stroke volume with elevated heart rate. For all subjects, compared to resting heart rate, an overall reduced cardiac-induced brain motion was observed with elevated heart rate (Figs. 4-5).Discussion

In this study, a higher heart rate caused an overall decrease in brain parenchyma motion based on aMRI. This effect is likely due to the rapidly changing blood flow combined with reduced CSF flow. Interestingly, the extent of heart rate elevation, and percentage change in CSF flow and brain parenchyma motion were variable among our cohort. Changes in brain pulsatility from exercise results in complex physiological processes simultaneously. Tarumi et al. [1] showed that RHG increased blood stroke volume in the internal carotid artery and vertebral artery and decreased CSF stroke volume in the aqueduct. We observed a similar increase in the carotid MCA flow and a consistent decrease in CSF flow. Apart from the obvious benefits of understanding the role of exercise on brain physiology, this work has revealed an important relationship between the heart rate and brain motion not well-defined previously. However, our work did not investigate potentially confounding effects from breathing and different band pass frequencies of aMRI. We also did not investigate the effects of possible sudden changes in heart rate during exercise. These are topics for further investigation.Conclusion

We detected changes in brain motion between rest and elevated heart rate conditions using a combination of PC-MRI blood/CSF flow imaging and aMRI to detect brain parenchyma motion. This study has revealed an important relationship between the heart rate and brain motion not well-defined previously. The approach here may open opportunities for probing the role of heart rate, brain fluid, and motion flow in various pathologies that affect the brain.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Royal Society of New Zealand Marsden Fund, Trust Tairāwhiti, JN & HB Williams Foundation, and the Kānoa - Regional Economic Development & Investment Unit, New Zealand. We are grateful to Mātai Ngā Māngai Māori for their guidance and to our research participants for dedicating their time toward this study. We would like to acknowledge the support of GE Healthcare.References

1. Tarumi T, Yamabe T, Fukuie M, Zhu DC, Zhang R, Ogoh S, Sugawara J. Brain blood and cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics during rhythmic handgrip exercise in young healthy men and women. J Physiol. 2021;599:1799-1813.

2. Enzmann DR, Pelc NJ. Brain motion: measurement with phase-contrast MR imaging. Radiology. 1992;185:653-660.

3. Poncelet BP, Wedeen VJ, Weisskoff RM, Cohen MS. Brain parenchyma motion: measurement with cine echo-planar MR imaging. Radiology. 1992;185:645-651.

4. Feinberg DA, Mark AS. Human brain motion and cerebrospinal fluid circulation demonstrated with MR velocity imaging. Radiology 1987;163:793–799.

5. Alperin N, Vikingstad EM, Gomez-Anson B, Levin DN. Hemodynamically independent analysis of cerebrospinal fluid and brain motion observed with dynamic phase contrast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:741-754.

6. Hirsch S, Klatt D, Freimann F, Scheel M, Braun J, Sack I. In vivo measurement of volumetric strain in the human brain induced by arterial pulsation and harmonic waves. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:671-683.

7. Holdsworth SJ, Rahimi MS, Ni W, Zaharchuk G, Moseley ME. Amplified magnetic resonance imaging (aMRI): Amplified MRI (aMRI). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;75(6):2245–2254. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26142

8. Terem I, Ni W, Goubran M, Rahimi MS, Zaharchuk G, Yeom K, Moseley M, Kurt M, Holdsworth SJ. Revealing sub-voxel motions of brain tissue using phase-based amplified MRI (aMRI): Terem et al. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2018;80(6), 2549–2559. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.27236

9. Terem I, Dang L, Champagne A, Abderezaei J, Pionteck A, Almadan Z, Lydon AM, Kurt M, Scadeng M, Holdsworth SJ. 3D amplified MRI (aMRI). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2021;86(3):1674–1686.

10. Abderezaei J, Pionteck A, Terem I, Dang L, Scadeng M, Morgenstern P, Shrivastava R, Holdsworth SJ, Yang Y, Kurt M. Development, calibration, and testing of 3D amplified MRI (aMRI) for the quantification of intrinsic brain motion. Brain Multiphysics. 2021;100022.

11. Nayler GL, Firmin DN, Longmore DB. Blood flow imaging by cine magnetic resonance. J Comput Assist Tomogr .1986;10:715–722.

12. Carr HY. Steady-state free precession in nuclear magnetic resonance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1958;112:1693-1701.

13. Oppelt A, Graumann R, Barfuss H, Fischer H, Hartl W, Shajor W: FISP - a new fast MRI sequence. Electromedica. 1986;54:15-18.

Figures