3006

Investigation of the ALDH2 genetic polymorphism effect in alcohol-related glymphatic dysfunction using DTI-ALPS1Department of Radiology, Graduate School of Medicine, Juntendo university, Tokyo, Japan, 2Department of Radiology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan, 3Faculty of Health Data Science, Juntendo University, Chiba, Japan, 4Sportology Center, Graduate School of Medicine, Juntendo university, Tokyo, Japan, 5Department of Metabolism & Endocrinology, Graduate School of Medicine, Juntendo university, Tokyo, Japan, 6Graduate School of Health and Sports Science, Juntendo University, Chiba, Japan, 7Department of Innovative Biomedical Visualization, Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya University, Aichi, Japan, 8Department of Radiology, Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya University, Aichi, Japan

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Glymphatic system, DTI-ALPS

Excessive alcohol intake seriously damages the brain. Previous animal studies reported that the glymphatic system, which is a brain waste clearance system via the cerebral spinal fluid, is affected by chronic high alcohol consumption. Glymphatic dysfunction is related to cognitive impairment. The changes of diffusivity along the perivascular space (ALPS) indices associated with heavy, moderate, and no‑alcohol intake and executive function with or without aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) rs671 polymorphism was evaluated. The present study revealed the glymphatic function and executive function decline in heavy drinkers. Furthermore, ALDH2 rs671 variants may increase vulnerability to alcohol-induced glymphatic dysfunction.Introduction

Long-term excessive alcohol consumption can affect the central nervous system and cause cognitive decline1. The glymphatic system hypothesis was recently proposed as a brain clearance system2 and glymphatic dysfunction is associated with amyloid-β accumulation and cognitive impairment3. Previous animal studies indicated that chronic heavy drinking might cause glymphatic dysfunction and increase the risk of dementia4. However, the human involvement in alcohol consumption is still unclear. This study aimed to evaluate the glymphatic function associated with alcohol consumption by diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS)5. Furthermore, the effect of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) genetic polymorphism on glymphatic function was compared.Materials and Methods

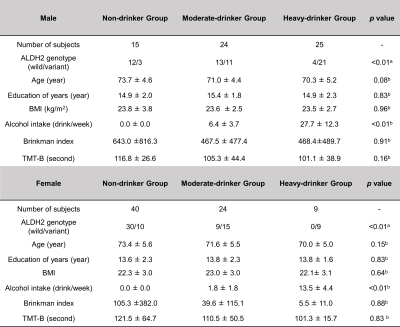

Study participantsIn this study, 137 community-dwelling Japanese older adults were enrolled from the Bunkyo Health study cohort6. Current alcohol consumption was assessed by a brief-type self-administered diet history questionnaire7. The subjects were divided into heavy-drinker (25 males and 9 females), moderate-drinker (24 males and 24 females), and non-drinker (15 males and 40 females) (Fig. 1). “Heavy drinking” was defined as >14 drinks (196 g) a week for men and >7 drinks (98 g) for women according to the US Federal Dietary guidelines8. ALDH2 rs671 genetic polymorphisms were analyzed with GG-type subjects as the ALDH2 wild-type group and GA- and AA-type subjects as the ALDH2 variants group. In this cohort, only the ALDH2 gene rs671 polymorphism was available for genetic data on alcohol metabolism.

MRI acquisition

MAGNETOM Prisma 3T MRI scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a 64-channel head coil was used to acquire all diffusion weighted images (DWI). Whole brain DWI were acquired using multislice echo-planar imaging along 64 diffusion gradient directions in the anterior–posterior direction at a b-value = 1000 s/mm2 with one nondiffusion-weighted (b = 0) volume using the following parameters: TR/TE = 3300/70 ms, matrix size = 130 × 130, resolution = 1.8 × 1.8 mm, slice thickness = 1.8 mm, FOV = 229 × 229 mm, and acquisition time = 7 min 29 s.

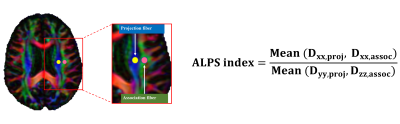

Analysis ALPS index

DWI data were analyzed using FSL version 6.0. A validated semi-automated pipeline was used to calculate the ALPS index9. In brief, a 5-mm diameter spherical regions of interest (ROIs) in the projection and association areas was placed (Fig. 2) using a color-coded FA map at the lateral ventricle body level. The x-, y-, and z-axis diffusivity values in the ROIs were obtained for each individual. In the lateral ventricular plane, medullary vessels run in the right–left (x-axis) direction. Perivascular spaces are oriented along the x-axis and white matter fibers (projection or association fiber) run orthogonally to the x-axis at that level. To estimate the perivascular space diffusivity, the ALPS index was calculated as the average x-axis diffusivity ratio of the projection (Dxxproj) and the association region (Dxxassoc) to the average y-axis diffusivity of the projection region (Dyyproj) and the average z-axis diffusivity of the association region (Dzzassoc) 5. (Fig. 2) Finally, the ALPS index was calculated by averaging the left and right sides.

Statistical analysis

A general linear model analysis was performed to compare the ALPS indices of the heavy-drinker, moderate-drinker, and non-drinker groups, including age, years of education, handedness, body mass index and the Brinkman index as covariates. Pairwise comparisons of groups were performed using Tukey's tests. In addition, the correlations between the ALPS indices and the time of the trail-making test part B (TMT-B) for drinking subjects after adjusting for age, years of education, handedness, body mass index and the Brinkman index was estimated. Analysis was divided between men and women, with and without ALDH2 variants. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.12.

Results

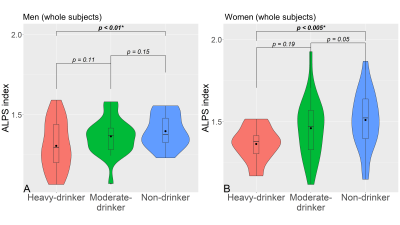

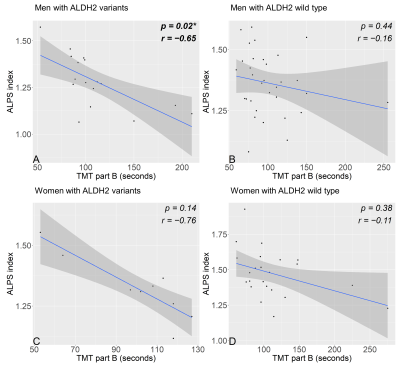

The male and female heavy-drinker groups had significantly lower ALPS indices than the non-drinker groups (Fig. 3). In men with ALDH2 variants, the heavy drinkers' ALPS index was significantly lower than in the other groups and also significantly lower in moderate drinkers than in non-drinkers. While there was no significant difference in ALDH2 wild-type men. In ALDH2 wild-type women, heavy drinkers had significantly lower ALPS indices than the moderate and non-drinker groups. While in women with ALDH2 variants, the ALPS index of moderate drinkers was significantly lower than non-drinkers (Fig. 4). In only drinking men, a significant negative correlation between the ALPS index and the TMT-B time (Fig. 5) was found.Discussion

This study showed significantly lower ALPS indices in heavy-drinker groups than in non-drinker groups in men and women. This means that in the heavy drinkers’ brains, there is a relative decrease in diffusivity along the perivascular space. The previous animal study reported that chronic alcohol exposure caused fluorescent tracer influx suppression along the cortical vessel4. Therefore, the ALPS index reduction could reflect alcohol-induced glymphatic dysfunction. Furthermore, male drinkers with ALDH2 variants were found to have decreased ALPS indices and a significantly negative correlation with executive function. Previous reports indicated chronic alcohol exposure caused amyloid-β accumulation in the brain of mice harboring ALDH2 variants10. ALDH2 genetic variant may cause executive function impairment in subjects due to alcohol-induced glymphatic dysfunction.Conclusion

This study suggested that heavy-drinking older adults have a decreased ALPS index and the ALDH2 genetic variant may increase vulnerability to alcohol-induced glymphatic dysfunction.Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI; Grant Numbers: 19K17244 and 18H02772), Brain/MINDS Beyond program (grant no. JP19dm0307101) of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), AMED under grant number JP21wm0425006, a Grant-in-Aid for Special Research in Subsidies for ordinary expenses of private schools from The Promotion and Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan, and the Juntendo Research Branding Project.References

1. Sabia S, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: 23 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. BMJ 2018;362:k2927.

2. Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid beta. Sci Transl Med 2012;4(147):147ra111.

3. Rasmussen MK, Mestre H, Nedergaard M. The glymphatic pathway in neurological disorders. The Lancet Neurology 2018;17(11):1016-1024.

4. Lundgaard I, Wang W, Eberhardt A, et al. Beneficial effects of low alcohol exposure, but adverse effects of high alcohol intake on glymphatic function. Scientific Reports 2018;8(1).

5. Taoka T, Masutani Y, Kawai H, et al. Evaluation of glymphatic system activity with the diffusion MR technique: diffusion tensor image analysis along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) in Alzheimer's disease cases. Japanese Journal of Radiology 2017;35(4):172-178.

6. Someya Y, Tamura Y, Kaga H, et al. Skeletal muscle function and need for long-term care of urban elderly people in Japan (the Bunkyo Health Study): a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2019;9(9):e031584.

7. Kobayashi S, Murakami K, Sasaki S, et al. Comparison of relative validity of food group intakes estimated by comprehensive and brief-type self-administered diet history questionnaires against 16 d dietary records in Japanese adults. Public Health Nutrition 2011;14(7):1200-1211.

8. Snetselaar LG, de Jesus JM, DeSilva DM, et al. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025: Understanding the Scientific Process, Guidelines, and Key Recommendations. Nutr Today 2021;56(6):287-295.

9. Kikuta J, Kamagata K, Takabayashi K, et al. An Investigation of Water Diffusivity Changes along the Perivascular Space in Elderly Subjects with Hypertension. American Journal of Neuroradiology 2022;43(1):48-55.

10. Joshi AU, Van Wassenhove LD, Logas KR, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 activity and aldehydic load contribute to neuroinflammation and Alzheimer's disease related pathology. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019;7(1).

Figures

Fig. 1 Demographic characters of subjects

Statistical analyses are performed using Fisher's exact test (a) and Kruskal–Wallis test (b).

Abbreviation: Aldehyde dehydrogenase 2, ALDH2 BMI, body mass index; TMT-B, Trail making test part B

Fig. 3 The violin plot of the ALPS index in men and women subjects divided by alcohol consumption

(A) represents the results of the three-group comparison for all men and (B) shows all women subjects.

Fig. 4 The ALPS index violin plot in men and women divided by alcohol consumption and ALDH2 genetic polymorphism

(A), (C) indicates the three-group comparison results of men and women with ALDH2 variants and (B), (D) shows men and women subjects without ALDH2 variants.

Fig. 5 The correlation scatter plot between the ALPS index and the score of Trail-making test part B and male and female drinking subjects divided ALDH2 genetic polymorphism

(A) indicates a significant negative correlation between the ALPS index and TMT-B in male drinking subjects with ALDH2 variants. (B) shows no significant correlation between the ALPS index and TMT-B in male drinking subjects with ALDH2 wild type. (C), (D) demonstrate no significant negative correlation between the ALPS index and TMT-B in female drinking subjects with or without ALDH2 polymorphism.