3000

Paravascular Fluid Dynamics Reveal Arterial Stiffness Assessed using Dynamic Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (dDWI)1Indiana University, School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, United States, 2Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering Department, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neurofluids, Aging

We recently developped a novel technique, dynamic diffusion-weighted imaging (dDWI), for measuring paravascular cerebrospinal fluid (pCSF) dynamics. In this work, we evaluated the time shifts between the pulsation-driven pCSF waves (measured by dDWI) and finger pulse waves (measured by scanner’s built-in finger pulse oximeter) to calculate brain-finger pulse wave travel time. Our preliminary results of an aging cohort support that the dDWI-derived brain-finger TimeDelay can be a surrogate for arterial stiffness. This method can be used as an add-on analysis to the recently developed dDWI framework to offer information about the participant’s vascular conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Paravascular cerebrospinal fluid (pCSF) surrounding the cerebral arteries is pulsatile and moves in synchrony with the pressure waves of the vessel wall. Whether such pulsatile pCSF can infer intracranial pulse wave propagation - a property tightly related to arterial stiffness - is unknown and has never been explored. Our recently developed technique, dynamic diffusion-weighted imaging (dDWI), captures pulsatile pCSF dynamics in the human brain and can potentially explore this idea (Wen et al, 2022). In this study, we aim to explore whether the pulsatile pCSF can provide a valuable pathway for assessing intracranial arterial integrity.METHODS

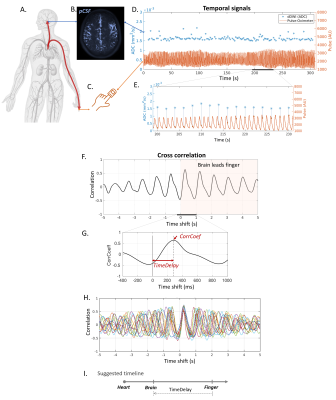

dDWI acquisition: dDWI applied a lower b-value of 150s/mm2 to sensitize to the slow flow of pCSF while suppressing the fast flow of adjacent arteries, as demonstrated in our recent work (Wen et al, 2022). Additional imaging parameters are: voxel size=1.8×1.8×4mm3, repetition time/echo time=1999ms/48.6ms, 24 slices, three cardinal diffusion encoding directions (x/y/z) with each diffusion direction repeated 50 times. Ten b=0s/mm2 were collected to calculate the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC). The total acquisition time was 5 minutes and 40 seconds. The scanner’s built-in wireless fingertip pulse oximeter was attached to the participant’s left index finger and was recorded continuously throughout the experiment.Brain-finger TimeDelay quantification: We evaluated the time shifts between pCSF waves (measured by dDWI) and finger pulse waves (measured by scanner’s built-in finger pulse oximeter [FPO]) to calculate brain-finger pulse wave travel time (Figure 1A-F). Voxel-wise brain-finger travel time was extracted based on cross-correlations between dDWI and FPO signals. The cross-correlation revealed that the pulse arrived at pCSF (brain) first and at the finger later (Figure 1G-I). The cross-correlation further showed strong and consistent correlations between pCSF pulse and finger pulse (Figure 1H, CorrCoeff=0.66±0.07 [mean±std]). TimeDelay was used to describe the brain-finger travel time.

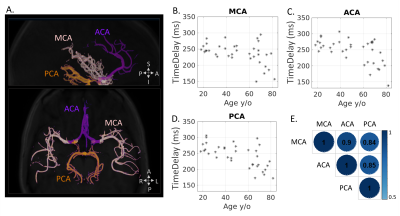

Regional TimeDelay quantification in three major cerebral arteries: To examine regional TimeDelay patterns, TimeDelay was quantified in pCSF regions along three major cerebral arteries, including middle cerebral arteries (MCA), anterior cerebral arteries (ACA), and posterior cerebral arteries (PCA) (Figure 2A). These arteries were identified using a cerebral artery atlas (Dunas et al., 2017).

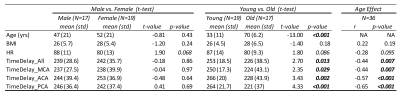

Human data collection and analysis: Two sets of analyses were conducted to evaluate the clinical relevance of TimeDelay. Firstly, we applied the framework to 36 participants aged 18-82 y/o (19 younger <50 y/o and 17 older ≥ 50 y/o) to study the age effect of TimeDelay. In the second analysis, we evaluated the association of TimeDelay with clinical variables in 15 older participants, including hypertension, blood pressure, and hippocampus-sensitive neurocognitive tests (i.e., Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test immediate (RAVLT_lm) and delayed (RVALT_Del) recall, and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)).

RESULTS

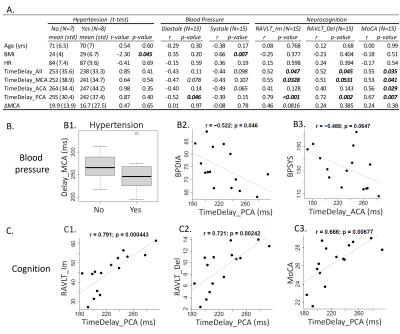

TimeDelay showed age effect: Brain-wide TimeDelay was significantly lower with advanced age (Person r=-0.44, p=0.007), with a mean±standard deviation being 253±19ms in young participants (18-50 y/o) and 236±39ms in the old (50-82 y/o) (Figure 3). Regional TimeDelay along three cerebral arteries showed all showed strong age effects (Figure 2A-E). The shorter TimeDelay in the older participants corresponds to faster pulse wave propagation and higher arterial stiffness.TimeDelay showed associations with hypertension, blood pressure, and cognition: Older participants with hypertension and higher blood pressure tended to have shorter TimeDelay, corroborating its relevance to arterial stiffness (Figure 4AB). TimeDelay was significantly associated with neurocognitive tests even after removing the age effect. Specifically, participants with shorter TimeDelay had lower (worse) RAVLT_Im, lower (worse) RAVLT_Del, and lower (worse) MoCA scores (Figure 4A, right panel). Of note, TimeDelay in PCA had the largest effect size with all neurocognitive tests, with Pearson’s r being 0.79, 0.72, and 0.67, respectively (Figure 4C [C1-C3]).

DISCUSSION

We introduced a novel approach for measuring pulse wave propagation through pulsatile pCSF fluctuations. The cross-correlation revealed a strong and consistent correlation between pCSF pulse and finger pulse (mean CorrCoeff=0.66), supporting arterial pulsation as a major driver for pCSF flow dynamics. Our preliminary data of the aging cohort support that the brain-finger TimeDelay can be a surrogate for arterial stiffness. Our data further highlighted a strong and consistent association between hippocampus-sensitive neurocognitive tests and regional TimeDelay in PCA. This finding aligned with the hippocampus vascularization supplied by short branches arising immediately from PCA and supported the hypothesis of cognitive decline due to hippocampal vascular dysfunction. This finding encourages future large-scale studies to evaluate the value of PCA TimeDelay in assessing hippocampal vascular dysfunction. Overall, our results demonstrated the feasibility of measuring pulse wave propagation through pCSF within the brain. The proposed TimeDelay calculation can be used as an add-on analytical method to the recently developed dDWI framework to offer information about the participant’s cerebral vascular integrity.Acknowledgements

The authors thank Mario Dzemidzic from Indiana University for the valuable feedback. This research was funded, in part, by multiple grants from the National Institute of Health, including R01 AG053993 and R01 NS112303, P30 AG010133, R01 AG019771, R01 AG057739, K01 AG049050, R01 AG061788, and R01 AG068193.References

Wen Q, Tong Y, Zhou X, Dzemidzic M, Ho CY, Wu YC. Assessing pulsatile waveforms of paravascular cerebrospinal fluid dynamics within the glymphatic pathways using dynamic diffusion-weighted imaging (dDWI). Neuroimage 2022; 260: 119464.

Dunas T, Wahlin A, Ambarki K, Zarrinkoob L, Malm J, Eklund A. A Stereotactic Probabilistic Atlas for the Major Cerebral Arteries. Neuroinformatics 2017; 15(1): 101-10.

Figures