2970

Changes of uterine morphology and endometrial T2 signal intensity in endometrial fibrosis1Department of Radiology, Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, Nanjing, China, 2Philips Healthcare, Shanghai, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Uterus, MR Value, Endometrial fibrosis; Magnetic resonance imaging; Noninvasive evaluation

Uterine morphology and endometrial T2 signal intensity can evaluate endometrial fibrosisPurpose

Accurate and non-invasive assessment of endometrial fibrosis helps clinicians to carry out timely anti-fibrotic treatment and evaluation of treatment effects. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has high soft tissue resolution and non-invasiveness and has been widely used to assess uterine morphological changes and tumors. We aimed to investigate the value of uterine morphological parameters and endometrial T2 signal intensity (T2-SI) in evaluating endometrial fibrosis.Methods

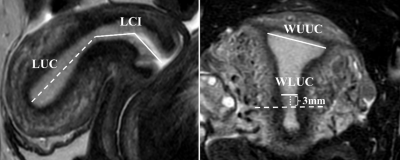

This study prospectively enrolled 64 patients with endometrial fibrosis diagnosed by hysteroscope (age range, 27-43 years; mean age, 33 years) and 46 healthy women (age range, 24-38 years; mean age, 28 years). MRI scans of all participants were performed on 3.0-T scanner (Ingenia, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands). The subjects were in the supine position, head-first orientation, and image acquisition was performed using a 16-channel phased array body coil. All participants were asked to empty their bladders before MRI scans to reduce beating artifacts. The MRI sequence included sagittal T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) of the uterus and coronal fat-suppressed T2WI of the uterus, with a total scan time of about 6 minutes and 11 seconds. The sequence parameters were as follows: repetition time/echo time=1700~5000ms/100ms, matrix=200×167, slice thickness=3 mm, slice spacing=0.3 mm, number of slices = 18, Field of view = 120 mm × 120 mm, voxel size = 0.60 mm × 0.72 mm. The length of uterine cavity (LUC), length of cervix and isthmus (LCI), width of upper uterine cavity (WUUC), width of lower uterine cavity (WLUC) and T2-SI of endometrium and adjacent subcutaneous fat were measured by a radiologist with nine years of experience in pelvic MRI reading who was blinded to clinical information on all subjects. The length of uterus (LU, the sum of LUC and LCI) and normalized endometrial T2-SI (nT2-SI, T2-SI of endometrium/T2-SI of adjacent subcutaneous fat) were calculated. The differences in uterine morphological parameters and endometrial nT2-SI between patients with endometrial fibrosis and healthy women were compared by independent t-test. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used to evaluate the efficacy of uterine morphological parameters and endometrial nT2-SI in diagnosing endometrial fibrosis.Results

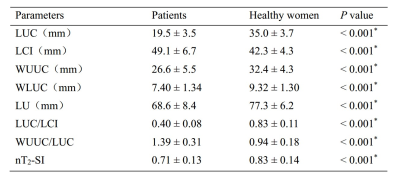

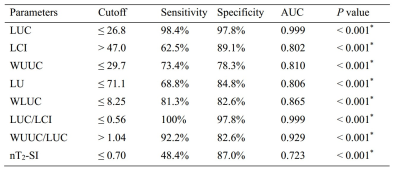

LUC (19.5 ± 3.5 mm vs. 35.0 ± 3.7 mm), WUUC (26.6 ± 5.5 mm vs. 32.4 ± 4.3 mm), WLUC (7.40 ± 1.34 mm vs. 9.32 ± 1.30 mm), LU (68.6 ± 8.4 mm vs. 77.3 ± 6.2 mm), LUC/LCI (0.40 ± 0.08 vs. 0.83 ± 0.11) and endometrial nT2-SI (0.71 ± 0.13 vs. 0.83 ± 0.14) in patients with endometrial fibrosis were significantly lower than that in healthy women, while LCI (49.1 ± 6.7 vs. 42.3 ± 4.3) and WUC/LUC (1.39 ± 0.31 vs. 0.94 ± 0.18) in patients with endometrial fibrosis were significantly higher than that in healthy women. Uterine morphological parameters have high accuracy in the diagnosis of endometrial fibrosis, and LUC and LUC/LCI show the highest accuracy in diagnosing endometrial fibrosis with an AUC of 0.999.Conclusions

As a noninvasive biomarker, uterine morphological parameters and endometrial nT2-SI can be used to evaluate endometrial fibrosis, which is helpful for clinicians to diagnose endometrial fibrosis and carry out anti-fibrosis therapy timely and to undergo dynamic follow-ups of therapeutic effect. This study is based on commonly used clinical magnetic resonance sequences, which is convenient for clinical promotion.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Song M, Zhao G, Sun H, et al. circPTPN12/miR-21-5 p/Np63alpha pathway contributes to human endometrial fibrosis. Elife. 2021;10: e65735.

2. Foix A, Bruno RO, Davison T, Lema B. The pathology of postcurettage intrauterine adhesions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1966;96(7):1027-1033.

3. Deans R, Abbott J. Review of intrauterine adhesions. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(5):555-569.

4. Azizi R, Aghebati-Maleki L, Nouri M, Marofi F, Negargar S, Yousefi M. Stem cell therapy in Asherman syndrome and thin endometrium: Stem cell- based therapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;102:333-343.

5. Jiang P, Tang X, Wang H, et al. Collagen-binding basic fibroblast growth factor improves functional remodeling of scarred endometrium in uterine infertile women: a pilot study. Sci China Life Sci. 2019;62(12):1617-1629.

6. Grimbizis GF, Gordts S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, et al. The ESHRE/ESGE consensus on the classification of female genital tract congenital anomalies. Hum Reprod[J]. 2013;28(8):2032-2044. 10. Munro SK, Farquhar CM, Mitchell MD, Ponnampalam AP. Epigenetic regulation of endometrium during the menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16(5):297-310.

7. Delong ER, Delong DM, Clarkepearson DI. Comparing the Areas under 2 or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves - a Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837-845.

Figures