2966

A two-perfusion IVIM model to account for both villous and trophoblast perfusion in the human placenta1Physics, CNR Institute for Complex Systems (ISC), Rome, Italy, 2Physics, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy, 3Radiological, Oncological and Pathological Sciences, Umberto I Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy, 4Maternal and Child Health and Urological Sciences, Umberto I Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Synopsis

Keywords: Placenta, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, IVIM, two-perfusion, villi, trophoblasts

The placenta may incur several pathologies during fetal growth due to perfusion impairment such as Fetal-Growth-Restriction (FGR) and the accretism. Two-perfusion IVIM model (with f1, D1*, f2, D*2 and D parameters) and IVIM model were used to fit data. DWIs were corrected for distributed noise χ. Mean-values differences of the quantified parameters in diseased and healthy placentas were analyzed by ANOVA test. The slower f2 perfusion fraction associated with trophoblastic perfusion was significantly lower in FGR compared to normal placenta, whereas the faster f1, quantifying villi perfusion fraction, was higher in the accretism compared to healthy placenta zone.Introduction

The placenta is a highly perfused tissue with crucial physiological functions to allow fetal development [1, 2]. Normal placenta histology is characterized by copious villi with different structures and perfusion functions, and an appropriate placenta microstructural and microvascular maturation is at the basis of regular interchange between maternal and fetal circulation [3]. Placental vascular dysfunction and insufficiency are the most frequent causes of the reduction of Estimated Fetal Weight (EFW) in utero since fetoplacental circulation impairment and anomalies in villous development affect the capacity of the villous trophoblast to ensure nutrient and oxygen supply to the fetus, thus restricting fetal growth [4-6]. Fetal growth restriction (FGR) is associated with lower perinatal, and postnatal outcomes than fetuses with normal birth weight (BWT) due to FGR placentae characterized by variable microstructural and micro-perfusion impairment [7]. Therefore, a proper in vivo assessment of placental perfusion and microarchitectural characteristics is crucial in the pregnancy management of all kinds of low-EFW. The accretism is characterized by the absence of the decidua, thus the organ infiltrates the myometrium. The infiltration site is highly perfused, and it could cause hemorrhages during the pregnancy, in particular the delivery. Depending on the infiltration grade, it could also bring on a hysterectomy [8]. Currently, the macroscopic vascularization of the placenta in-vivo is monitored by UltraSonography (US) with Doppler examination. Nevertheless, current evidence suggests that Doppler examination alone has limitations since it is not able to assess micro-perfusive placental qualities [9, 10]. In addition, a recent paper highlighted the potential of IVIM model in the discrimination among normal, FGR and small for gestational age (SGA) fetuses [11] not obtainable using conventional Doppler examination.Methods

Here, we tested the potential of a modified IVIM model to investigate the human placenta in vivo, considering two perfusion and one diffusion compartments:$$\frac{S(b)}{S(0)} = f_1 e^{-b(D_1^*+D_2^*+D)}+f_2 e^{-b(D_2^*+D)} + (1-f_1-f_2)e^{-bD}$$

Where f1 is the fastest perfusion fraction, f2 is the slowest perfusion fraction, D1* is the fastest perfusion coefficient, D2* is the slowest perfusion coefficient and D the diffusion coefficient. In order to decrease the number of parameters to be fitted, the diffusion coefficient D was previously estimated performing a mono-exponential fit using the highest b-values (from 200 to 1000 s/mm2) DWIs, then an IVIM model was fitted to the data in order to fix the sum of the two perfusion fractions of the new model: f1+f2=f.

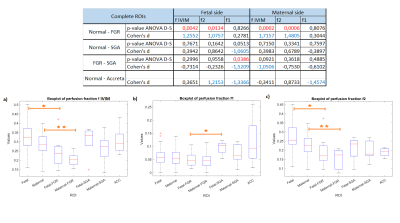

Row data come from a cohort of 65 pregnancies: 43 healthy subjects, 8 FGR, 7 SGA and 7 accretism. Diffusion-weighted images (DWIs) were acquired at 1.5T using b-values = 0,10,30,50,75,100,200,400,700,1000s/mm2 and considering only the diffusion trace along three directions. Images were noise corrected for a stationary χ distribution [12]. Both IVIM parameters (f, D and D*) and the two-perfusion modified IVIM parameters (f1, f2, D, D1*, D2*) were quantified in fetal and maternal placental sides. The resulting data were analyzed calculating the Cohen’s d and performing the ANOVA test with Dunn and Sidák’s post-hoc correction. Parametric maps were obtained using a Machine Learning bugged tree algorithm (Figure 1).

Results

We found that the higher values of f for healthy subjects compared to FGR placentas is given by the slowest contribution of the “trophoblastic” compartment f2 which is lower on FGR pathological tissues. The fastest f1 perfusion fraction was found higher on the fetal side of SGA placentas than on FGR subjects. The accretism zone was found to be characterized by higher values of the perfusion fraction f1 compared to healthy placentas. Conversely, f cannot discriminate between accreta and healthy placenta. The results are shown in Figure 2Discussion

The f2 differences between FGR and healthy placentas might be due to the insufficient exchange of nutrients between the maternal and the fetal blood given by the pathology. On the contrary, SGA subjects shows higher values of f1, probably due to the villi compartment which have increased its volume in order to overcome any exchanging insufficiency. The accretion zone had the highest values of f1 underlining the high perfusivity which characterized the accretion zone’s tissues.Conclusion

The two-perfusion fractions f1 and f2 are promising biomarkers for vascular placental pathology. In fact, they seem to discriminate between pathological and normal placental tissues reflecting the pathologies’ characteristics. f1 quantifies the fastest perfusion compartment due to the activity of villi and arteries whereas f2 is related to the slowest perfusion compartment due to the trophoblastic cells’ activity.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] K. Benirschke, S.G. Driscoll, The Pathology of the Human Placenta BT - Placenta, in: F. Strauss, K. Benirschke, S.G. Driscoll (Eds.), Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1967: pp. 97–571.

[2] A.S. Serov, C.M. Salafia, M. Filoche, D.S. Grebenkov, Analytical theory of oxygen transport in the human placenta, J. Theor. Biol. 368 (2015) 133–144.

[3] T.R.H. Regnault, H.L. Galan, T.A. Parker, R.V. Anthony, Placental Development in Normal and Compromised Pregnancies— A Review, Placenta. 23 (2002) S119–S129.

[4] F. Barut, A. Barut, B.D. Gun, N.O. Kandemir, M.I. Harma, M. Harma, E. Aktunc, S.O. Ozdamar, Intrauterine growth restriction and placental angiogenesis, Diagn. Pathol. 5 (2010) 24.

[5] G.J. Burton, E. Jauniaux, Pathophysiology of placental-derived fetal growth restriction, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 218 (2018) S745–S761.

[6] F. Lackman, V. Capewell, R. Gagnon, B. Richardson, Fetal umbilical cord oxygen values and birth to placental weight ratio in relation to size at birth, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 185 (2001) 674–682.

[7] I. Günyeli, E. Erdemoğlu, S. Ceylaner, S. Zergeroğlu, T. Mungan, Histopathological analysis of the placental lesions in pregnancies complicated with IUGR and stillbirths in comparison with noncomplicated pregnancies, J. Turkish Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 12 (2011) 75–79.

[8] E. Jauniaux, S. Collins and G. Burton, Placenta accreta spectrum: pathophysiology and evidence-based anatomy for prenatal ultrasound imaging, American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 218 (2018) 75–87.

[9] A.T. Papageorghiou, C.K.H. Yu, K.H. Nicolaides, The role of uterine artery Doppler in predicting adverse pregnancy outcome, Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 18 (2004) 383–396.

[10] S. Gudmundsson, M. Dubiel, P. Sladkevicius, Placental Morphologic and Functional Imaging in High-Risk Pregnancies, Semin. Perinatol. 33 (2009) 270–280.

[11] Amanda Antonelli, Silvia Capuani, Giada Ercolani, Miriam Dolciami, Sandra Ciulla, Veronica Celli, Bernd Kuehn, Maria Grazia Piccioni, Antonella Giancotti, Maria Grazia Porpora, Carlo Catalano, Lucia Manganaro, Human placental microperfusion and microstructural assessment by intra-voxel incoherent motion MRI for discriminating intrauterine growth restriction: a pilot study. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine (2022): 1-8.

[12] S. Aja-Fernández, A. Tristán-Vega, C. Alberola-López, Noise estimation in single- and multiple-coil magnetic resonance data based on statistical models. Magn. Reson. Imag. 27, (2009), 1397–1409.

Figures