2957

Self-contained comprehensive quantification of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI using physics+kinetics-based network learning (PKNet)1Medical Physics, MSKCC, New York, NY, United States, 2Radiology, MSKCC, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, DSC & DCE Perfusion, Deep Learning

This work develops a deep learning technique that is trained according to physics and kinetics for self-contained comprehensive quantification of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. In addition to perfusion parameters, patient-specific parameters that affect the quantification are estimated, including bolus arrival time, T1, steady state magnetization, and AIF. The DCE-MRI quantification network was tested on a patient with cervical cancer and demonstrated high concordance between two scans separated by 24 hours. Physics plus kinetics informed network learning (PKNet) enabled the quantification of multiple parameters which has the potential to increase reproducibility of quantitative DCE-MRI, a long-desired goal.Introduction

Despite extensive research work and promising results for cancer diagnosis and treatment response evaluation, quantitative perfusion parameters derived from dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) still play a very limited role in routine clinical practice [1,2]. One of the main causes has been the non-reproducibility of quantification results. DCE-MRI quantification is sensitive to patient-specific variables, such as T1, arterial input function (AIF), and bolus arrival time (BAT). The conventional approach of using population-based values or estimating these parameters using separate acquisitions results in poor quantification reproducibility [3]. This works develops a deep-learning approach to perform a self-contained comprehensive DCE-MRI quantification including perfusion parameters, T1, AIF and BAT from a single acquisition.Methods

Physics+kinetics quantification network (PKNet): Inspired by the DRONE method [4], which uses a neural network trained with Bloch equations to perform T1 and T2 mapping, this work uses the spoiled gradient-echo (SPGR) signal model [5] and the extended Tofts kinetic model [6] to train a neural network to map perfusion parameters (Ktrans,vp,ve), T1 and BAT. Three cases of AIF were considered: original Parker AIF [7], modified Parker AIF, and step function. The modified Parker AIF was generated by changing the a1 parameter shown in Eq.1 to lower the peak of the signal to match the temporal shape of the in vivo data. The step function uses an amplitude of a1.$$ C_b(t) = \sum_{n=1}^{2} \frac{a_n}{\sigma_n \sqrt{2 \pi}}e^{-\frac{(t-T_n)^2}{2\sigma_n^2}}+\alpha \frac{e^{-\beta t}}{1+e^{-s(t-\tau)}} \quad \quad eq.1 $$

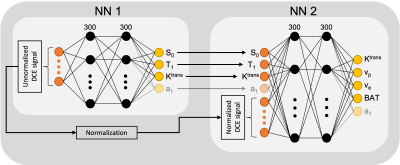

The architecture of PKNet is shown in Fig.1, which consists of two fully-connected sub-networks (fours layers with 300 nodes for each hidden layer) trained to convergence with Adam optimizer [8]. The first sub-network works with the unnormalized DCE signal and estimates all the parameters affected by the amplitude of the signal, including steady state magnetization (S0), T1, Ktrans and a1. The second sub-network works with the normalized DCE signal and the output of the first sub-network to update Ktrans and estimate vp, ve and BAT. The two sub-networks were separately trained using 200,000 realizations of the DCE signal given by variations of all the estimated parameters and the acquisition parameters used for in vivo scans.

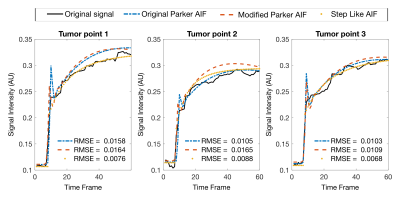

In vivo validation on a patient with cervical cancer: DCE-MRI acquisition was performed on a patient with cervical cancer using a fat-suppressed T1-weighted stack-of-stars k-space acquisition on a 3T scanner (Signa Premier, GE Healthcare) with the following parameters: FOV=400mm×400mm, TR/TE= 3.224/1.48msec, FA= 12°, scan time ~= 6.3min. Gadavist with a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg was administered intravenously followed by a 20 ml saline flush at 3 ml/s using a power injector. A second scan was performed on the same patient after 24 hours to test reproducibility. Dynamic images were reconstructed using the Golden-angle radial sparse parallel (GRASP) [9] method with a 5-second temporal resolution. The performance of the AIF models was compared using the goodness of fit, which was calculated as the root mean square error (RMSE) between the acquired DCE signal and the fit. Bland-Altman plots were computed to assess reproducibility between the two scans.

Results

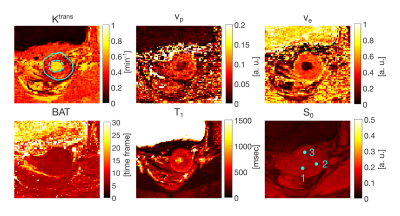

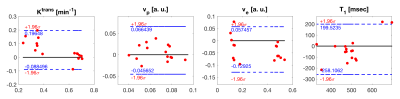

The step AIF presented the highest goodness of fit (or lowest RMSE) and hence was selected as the AIF for subsequent analysis. Visually, the step AIF also outperforms the other two AIF models with a fit that is closer to the acquired DCE signal (Fig.2). The perfusion maps and T1 and BAT maps are shown in Fig.3 for the model with step AIF. The tumor (solid line) is well highlighted in all the maps. The BAT matches the timing of contrast injection.Bland-Altman plots (Fig.4) show good agreement between the two scans performed on the same patient for several small regions of interest (ROIs) defined on the tumor (solid line in Fig.3) and the mucosa of the cervical canal (dashed line in Fig.3) and iliac bone. The 95% confidence range ($$$\pm$$$1.96$$$\sigma$$$) contains the majority of the data points.

Discussion

This work demonstrated the feasibility of a one-stop-shop for quantitative perfusion analysis of DCE-MRI data using deep learning. The use of a neural network enabled to solve complex MR physics and DCE kinetic equations to estimate perfusion parameters and several other variables that can affect quantification performance from a single acquisition. T1 estimation was performed in a novel way based on contrast enhancement, which does not require a separate acquisition. One caveat is that T1 cannot be estimated in regions with low contrast enhancement, such as fat, which nevertheless did not affect quantification performance in the tumor. Another significant advantage of the proposed network is patient images are not required for training, since training was performed using MR physics and DCE kinetic models. The quantification of the sensitivity of conventional DCE acquisitions to T1 errors in comparison to that of PKNet is left for future work.Conclusion

A deep-learning network trained with MR physics and DCE kinetic models was demonstrated for self-contained comprehensive quantification of DCE-MRI data from a single acquisition. In addition to perfusion parameters, PKNet estimated other variables affecting performance such as T1 and BAT, and the effect of the AIF was taken into account. Comprehensive DCE quantification is expected to improve reproducibility and promote the routine clinical use of DCE-MRI, which is a long desired goal.Acknowledgements

SK and OC had equal contribution.References

[1] Shukla-Dave A, Obuchowski NA, Chenevert TL, Jambawalikar S, Schwartz LH, Malyarenko D, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers alliance (QIBA) recommendations for improved precision of DWI and DCE-MRI derived biomarkers in multicenter oncology trials. 2019 Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging;49:e101–e121.

[2] Little RA, Barjat H, Hare JI, Jenner M, Watson Y, Cheung S, et al. Evaluation of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI biomarkers for stratified cancer medicine: How do permeability and perfusion vary between human tumours? 2018 Magnetic Resonance Imaging;46:98–105.

[3] Priest AN, Gill AB, Kataoka M, McLean MA, Joubert I, Graves MJ, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in ovarian cancer: Initial experience at 3 tesla in primary and metastatic disease. 2010 Magnetic Resonance in Medicine;63:1044–1049.

[4] Cohen O, Zhu B, Rosen MS. MR fingerprinting Deep RecOnstruction NEtwork (DRONE). 2018 Magnetic Resonance in Medicine;80:885–894.

[5] Frahm J, Haase A, Matthaei D. Rapid NMR imaging of dynamic processes using the FLASH technique. 1986 Magnetic resonance in medicine;3:321–7.

[6] Tofts PS. Modeling tracer kinetics in dynamic Gd-DTPA MR imaging. 1997 Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI;7:91–101.

[7] Parker GJM, Roberts C, Macdonald A, Buonaccorsi GA, Cheung S, Buckley DL, et al. Experimentally-derived functional form for a population-averaged high-temporal-resolution arterial input function for dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI. 2006 Magnetic resonance in medicine;56:993–1000.

[8] Kingma DP, Ba JL. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization; 2015.

[9] Feng L, Grimm R, Block KT, Chandarana H, Kim S, Xu J, et al. Golden-angle radial sparse parallel MRI: Combination of compressed sensing, parallel imaging, and golden-angle radial sampling for fast and flexible dynamic volumetric MRI. 2014 Magnetic Resonance in Medicine;72:707–717.

Figures