2951

Respiratory Motion Artifact Simulation for DL application in Cardiac MR Image Quality Assessment1Biomedical Engineering, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, Netherlands, 2MR R&D - Clinical Science, Philips Healthcare, Eindhoven, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Artifacts, Respirator Artifact Simulation

To tackle data scarcity for training a deep-learning algorithm for cardiac MR image quality assessment, we develop a k-space method for simulating respiratory motion artifacts with different levels of severity on artifact-free publicly available cardiac MRI data. The benefit of such simulated data is investigated, demonstrating the usefulness of training a feature extractor with the simulated artifacts for image quality classification. Our proposed method achieved the test accuracy of 0.625 and Cohen's Kappa of 0.473 (n=120 images), ranking third in task one for the CMRxMotion challenge of MICCAI 2022.

Introduction

Respiratory motion introduces inconsistency in the k-space data between different segments and the severity of the artifact depends on the phase-encoding order and timing of the motion [1]. Such artifacts represent a significant challenge in the clinical deployment of deep learning (DL) automated image analysis algorithms. The Extreme Cardiac MRI Analysis Challenge under Respiratory Motion (CMRxMotion) [2] dataset was acquired with deliberate patient motion, of varying degrees, to allow the study of these problems.In this paper, we propose a solution for the task of image quality assessment in the presence of respiratory motion artifacts. To augment the training data and tackle the medical data scarcity, we develop a k-space based approach to simulate motion artifact on artifact-free images from previous publicly available cardiac MR databases of M&Ms-1 [3] and M&Ms-2 challenges. We simulate images with different levels of respiratory motions and use these motion-corrupted images for training the proposed deep-learning model.

Methods

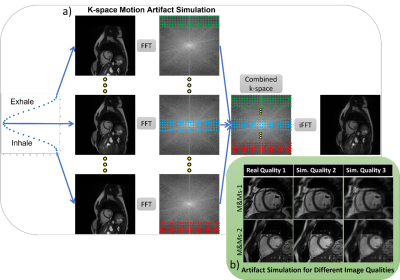

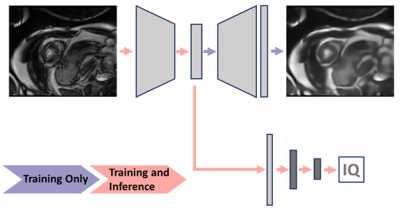

Simulation of Respiratory Motion Artifact; Inspired by prior works on k-space based artifact simulation for brain motion [4] and respiratory motion[5], [6], we model motion artifacts by applying translation to artifact-free images before transforming them to the Fourier domain. As depicted in Figure 1, the breathing motion is modeled as a simple sinusoidal translation of the image in one direction, as the first-order approximation. We assume that the k-space data is acquired in multiple blocks of segments at different respiration points corresponding to different translation amounts. The combined k-space is composed of different sections (indicated with different colors) from the k-space data for each translated image. The final motion-corrupted image is generated by transforming the combined k-space to the image domain via inverse Fourier transformation. We can change the severity of the motion artifact by tuning two parameters; the period of sinusoidal function corresponding to the number of breathing cycles during the acquisition time window and the amplitude corresponding to the maximum translation of organs during acquisition, i.e. breathing intensity. Note that for simplicity, we assumed a one-dimensional homogeneous translation of all organs for modeling the breathing motion.Image Quality Assessment; We train an auto-encoder to take an input image with simulated motion artifacts and to reconstruct the original image without artifacts. The reconstruction residual could be used for classification, however, recent work by Meissen et al. discussed the pitfalls of this [7]. Therefore, fully-connected layers are added to the encoder to directly predict the image quality score, and this is trained with training data and image quality labels from the CMRxMotion challenge. In other words, we are pre-training the feature extractor of a classification model to learn features relevant to the motion artifacts, and then combining this with the classification layers and re-training to directly predict the image quality score. The image quality predictions are trained on a slice-by-slice basis and the slice-wise predictions are combined to a single prediction for each image stack (one each for the end-diastolic and end-systolic images, as provided for the challenge). The pipeline is visualized Figure 2.

Experiments and Results

To evaluate the benefit of our proposed approach, its performance is compared against the corresponding baseline models. The classification model with the pre-trained feature extractor is compared to a corresponding model trained from scratch. The model with the optimized decision threshold for severe motion class is further compared to the same model using only the largest summed probability for classification. These model evaluations are performed on the validation data set of the CMRxMotion challenge with the best model chosen for submission to the challenge testing phase.The normalized mean squared reconstruction residual between the IQ3 images and both IQ1 and IQ2 was significantly different (both p < 0.01), but there is substantial overlap between the classes and there is no significant difference between IQ1 and IQ2 (p = 0.29). It is, thus, clear that the reconstruction cannot be used directly for classification. The pre-trained classification model with an optimized decision threshold achieved a classification accuracy of 0.75, and a Cohen's kappa coefficient of 0.64 on the validation data of the challenge. This improved over the baseline models using the model trained from scratch and the model without optimized decision threshold which gave accuracy and Cohen’s kappa coefficient of 0.58 and 0.32, and 0.68 and 0.42, respectively. Our final submitted method achieved the test (n=120 images) accuracy of 0.625 and Cohen's Kappa of 0.473, ranking third in the CMRxMotion challenge.

Discussion and Conclusion

We demonstrated that our simple k-space based motion simulation approach was effective in handling data scarcity by simulating different levels of motion artifacts on artifact-free publicly available cardiac MR images. While we modeled the organ motions due to breathing as a simple sinusoidal translation, the heart and organ motion during breathing is more complex, involving rotation and deformation.Classification of images by the level of motion artifacts was found to be challenging and modest accuracy and Cohen’s kappa coefficient were reported. The limited amount of training data contributed to the challenge of this task. It also exacerbated the class imbalance problem leading to very few images with severe motion artifacts, although, this was improved through the use of simulated data.

Acknowledgements

References

[1] P. F. Ferreira, P. D. Gatehouse, R. H. Mohiaddin, and D. N. Firmin, “Cardiovascular magnetic resonance artefacts,” Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–39, May 2013, doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-15-41/FIGURES/10.

[2] S. Wang et al., “The Extreme Cardiac MRI Analysis Challenge under Respiratory Motion (CMRxMotion),” Oct. 2022, doi: 10.48550/arxiv.2210.06385.

[3] V. M. Campello et al., “Multi-Centre, Multi-Vendor and Multi-Disease Cardiac Segmentation: The MMs Challenge,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 40, no. 12, pp. 3543–3554, Dec. 2021, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2021.3090082.

[4] R. Shaw, C. H. Sudre, T. Varsavsky, S. Ourselin, and M. J. Cardoso, “A k-Space Model of Movement Artefacts: Application to Segmentation Augmentation and Artefact Removal,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 39, no. 9, pp. 2881–2892, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2020.2972547.

[5] I. Oksuz et al., “Automatic CNN-based detection of cardiac MR motion artefacts using k-space data augmentation and curriculum learning,” Med Image Anal, vol. 55, pp. 136–147, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.1016/J.MEDIA.2019.04.009.

[6] B. Lorch, G. Vaillant, C. Baumgartner, W. Bai, D. Rueckert, and A. Maier, “Automated Detection of Motion Artefacts in MR Imaging Using Decision Forests,” J Med Eng, vol. 2017, pp. 1–9, Jun. 2017, doi: 10.1155/2017/4501647.

[7] F. Meissen, B. Wiestler, G. Kaissis, and D. Rueckert, “On the Pitfalls of Using the Residual as Anomaly Score.” Jun. 22, 2022.

Figures