2944

Association of neuroanatomical changes with neuropsychological changes in Treated Adult HIV-Positive Patients1Radiological Sciences, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Division of HIV Medicine, Lundquist Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 3Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 4Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, School of Medicine,, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States, 5School of Nursing and Brain Research Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Processing, Brain

This study was designed to use the structural MRI data to characterize volumetric changes in gray matter and white matter, and to determine variations in cortical thickness, in a group of HIV-infected individuals to understand how their brain structural changes are associated with their neuropsychological state compared to a group of healthy individuals with similar social, behavioral backgrounds. Despite the demographic similarities and cART, we observed reduced gray and white matter volumes, as well as altered cortical thickness in HIV-infected participants compared with healthy controls. In addition, the neuroanatomic changes in HIV-infected patients showed statistically significant correlations with memory scores.Introduction

HIV-induced cognitive impairment continues to be a concerning factor in HIV-infected individuals despite the reduced risk of major neurological complications with the introduction of potent antiretroviral therapy (ART) (1-5). HIV-associated dementia is commonly observed in HIV-infected individuals (6,7). Altered brain volume of HIV-infected individuals in various cortical and subcortical regions that support cognition have been reported in many neuroimaging studies (8-10). The purpose of this study is to use the structural MRI data to characterize volumetric changes in gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM), as well as to determine variations in cortical thickness (CT), in a group of HIV-infected individuals to understand how their brain structural changes are associated with their neuropsychological state compared to a group of healthy induvial with a similar social, behavioral backgrounds.Materials and Methods

We investigated 27 HIV-infected participants (age:44.27±10.89 years) and 15 age-matched healthy controls (HC) (age:49.41±9.35 years). Brain MR imaging data were collected on Siemens 3T MRI scanner, using a 16-channel head ‘receive’ coil. High-resolution 3D T1-weighted images were acquired using a magnetization-prepared-rapid-acquisition gradient-echo (MP-RAGE) sequence (TR/TE=2200/2.41ms; inversion time=900ms; flip angle=9°; matrix size=320×320; FOV=230×230 mm; slice thickness=0.9 mm; pixel bandwidth=200Hz, 192 slices). We excluded volunteers with current alcohol or other substance use/abuse, current or past attention deficit disorder, active depression or other psychiatric diagnoses, metabolic disturbances, metallic implants, claustrophobia, pregnancy, and non-HIV-related brain diseases from both groups. Voxel based and surface based morphometric analysis were performed in MATLAB using the Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12, http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat/), which is an extension of SPM12 (https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/) (11-12). The standard processing pipeline of CAT12 allows extraction of CT, GM volume (GMV) and WM volume (WMV). A 2-sample t-test using CAT12 was used for statistical analysis of the data. The significance level of p<0.001 was used for GMV and WMV changes in voxel-based morphometry. Threshold of p<0.05 for region-of-interest analysis (surface measurements) with Holm-Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was used. The t-test for CT used age and gender as covariates while total intracranial volume (TIV), age and gender were used as covariates for GM and WM. We used the ratios of GM, WM and CSF with TIV for correlation analysis to account for the changes in head-size (13-15).Results

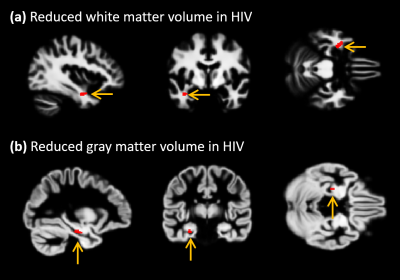

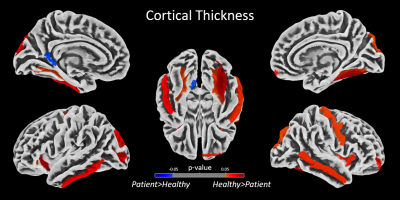

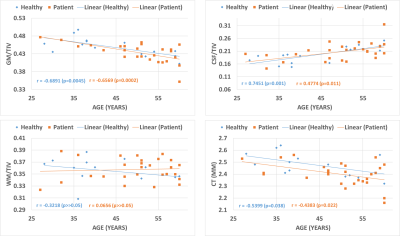

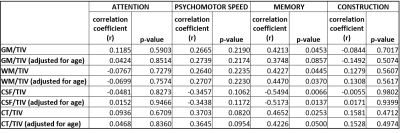

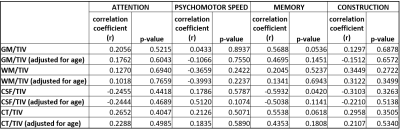

Despite the demographic similarities and cART, reduced WMV and GMV were observed in HIV-infected participants compared with healthy controls. WMV was reduced in the left hemisphere (LH) in the sub-gyral part of the temporal lobe, and left hippocampus in the limbic lobe as shown in Fig.1(a). The reduction of GMV appeared in the parahippocampal gyrus in LH as shown in Fig.1(b). No significant reduction in WMV or GMV was observed in right hemisphere (RH). Regions with significantly elevated WMV or GMV was not observed in either LH or RH. No significant differences were observed between HIV-infected participants and HC for global WM and global CSF volumes, as well as the global GM/TIV, WM/TIV and CSF/TIV ratios. However, the reduction in global CT and GM volumes was found to be statistically significant for p<0.001. Surface based analysis showed multiple clusters with significantly altered (thicker and thinner) CT in HIV-infected participants for p<0.05, including bilateral para hippocampal region as shown in Fig.2. The correlation analysis of GMV, WMV and CT with age for HIV-infected patients and HC are shown in Fig.3. Significant negative correlation of CT and GM/TIV ratio with age was found in HIV infected participants. While CSF/TIV ratio was found to be significantly positively correlated with age, the WM/TIV ratio was not correlated among the HIV-infected participants. Partial correlation analysis of these ratios with the results of neuropsychological analysis, controlling for the influence of age, showed the moderate correlation of the brain volumetric changes with memory scores of HIV-infected participants, as shown in Table 1, which were also statistically significant for P value < 0.05. The results of healthy controls are shown in Table 2, where the correlations were not statistically significant.Discussion

Shrinkage of WMV and GMV in HIV-infected participants as compared to HC in the parahippocampal region was observed. Since the WM tracts in this region connect hippocampus to other regions of the brain and the entorhinal cortex contained in the parahippocampal gyrus provides input to hippocampus, alterations in this region can adversely affect the memory of HIV-infected subjects. SBM analysis showed that the reduced GM and WM volume in the parahippocampal region could be due to cortical thinning, which could be due to the neuronal and glial cell injury resulting from HIV infection (6,7). Even though we identified a significant correlation between GM/TIV, CT and CSF/TIV with age, the partial correlation analysis controlling for the effect of age showed that the HIV-infected participants with significant volumetric changes in the parahippocampal region have an associated change in memory scores as well. These results are consistent with HIV-associated dementia observed in HIV-infected individuals (6,7).Conclusion

Volumetric changes in GM, WM and alterations in CT were observed in HIV-infected patients compared to healthy control in the brain regions affecting memory. Consequently, the changes in GM, WM, CSF and CT showed moderately strong correlations with memory scores for HIV-infected participants.Acknowledgements

Authors like to acknowledge the support of Dr. Manoj K Sarma and Dr. Charles Hinkin during the earlier acquisition and study design, Mr. Anwar Khalid during the data reconstruction, and Ms. Victoria Rueda during the study subject recruitment. This work is supported by National Institute of Health grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (5R21NS086449-02) and National Institute of Mental Health (5R21MH125349–02).References

1. Effros RB, Fletcher CV, Gebo K, Halter JB, Hazzard WR, Horne FM, Huebner RE, Janoff EN, Justice AC, Kuritzkes D. Workshop on HIV infection and aging: what is known and future research directions. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2008; 47: 542.

2. Justice AC, Modur S, Tate JP, Althoff KN, Jacobson LP, Gebo K, Kitahata M, Horberg M, Brooks J, Buchacz K. Predictive accuracy of the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS) index for mortality with HIV infection: a north American cross cohort analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;62: 149.

3. Mack KA, Ory MG. AIDS and older Americans at the end of the Twentieth Century. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003;33: S68-75.

4. Heaton R, Clifford D, Franklin D, Woods S, Ake C, Vaida F, Ellis R, Letendre S, Marcotte T, Atkinson J. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology 2010; 75: 2087-2096.

5. Nweke M, Nombeko M, Govender N, Akinpelu AO, Ukwuoma M. Impact of HIV-associated cognitive impairment on functional independence, frailty and quality of life in the modern era: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2022;12: 1-10.

6. Kaul M, Garden GA, Lipton SA. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature 2001;410: 988-994.

7. Glass JD, Fedor H, Wesselingh SL, McArthur JC. Immunocytochemical quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus in the brain: correlations with dementia. Annals of Neurology: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society 1995; 38:755-762.

8. Ances BM, Hammoud DA. Neuroimaging of HIV associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014;9: 545.

9. Holt JL, Kraft-Terry SD, Chang L. Neuroimaging studies of the aging HIV-1-infected brain. J Neurovirol 2012;18: 291-302.

10. Joy A, Nagarajan R, Daar ES, Paul J, Saucedo A, Yadav S, Guerrero M, Haroon E, Macey P, Thomas MA. Alterations of gray and white matter volumes and cortical thickness in treated HIV-positive patients. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2023,95:27-38.

11. Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Voxel-based morphometry--the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11:805-21

12. Dahnke, Robert et al. “Cortical thickness and central surface estimation.” NeuroImage vol. 65 (2013): 336-48.

13. Cohen RA, Harezlak J, Schifitto G, Hana G, Clark U, Gongvatana A, Paul R, Taylor M, Thompson P, Alger J. Effects of nadir CD4 count and duration of human immunodeficiency virus infection on brain volumes in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. J Neurovirol 2010; 16: 25-32.

14. Di Sclafani V, Mackay RS, Meyerhoff DJ, Norman D, Weiner MW, Fein G. Brain atrophy in HIV infection is more strongly associated with CDC clinical stage than with cognitive impairment. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 1997; 3: 276-287.

15. Ragin AB, Wu Y, Gao Y, Keating S, Du H, Sammet C, Kettering CS, Epstein LG. Brain alterations within the first 100 days of HIV infection. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2015;2: 12-31.

Figures