2931

Multicoil Deep Equilibrium MRI Reconstruction1Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin Madison, Madison, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Brain

Deep equilibrium (DEQ) image reconstruction models have demonstrated improved performance while remaining memory efficient for single coil MRI reconstructions; however, DEQ models are known to be susceptible to model drift due to variabilities in the forward model. In the case of multicoil MRI, the forward model is changed due to the sampling patterns and coil sensitivity encoding. In this work, we implemented a multicoil DEQ model and analyzed model drift with respect to the coil sensitivities.Introduction

Multicoil MRI is a classic example of physics-based acceleration to facilitate faster MRI data acquisition. Recently, deep learning-based (DL) MRI reconstructions have been developed to further accelerate data acquisition and reduce image reconstruction time. Model-based DL (MoDL) approaches alternate between minimizing a data consistency term and a CNN based regularizer term to constrain the solution.1 However, reconstruction with MoDL architecture presents significant challenges due to large memory footprint that scales with number of unrolls. To alleviate the issue, gradient checkpointing approaches2 have been proposed to reduce memory footprint; however, these approaches slow training and can still lead to high memory requirements. Recently introduced deep equilibrium (DEQ)3 models require one implicit layer run to convergence instead of unrolling for backpropagation effectively reducing memory consumption markedly. This was demonstrated to outperform unrolled MoDL for single-coil MRI reconstruction.4 However, the effectiveness of DEQ for multi-coil MRI is an open ended question, as the DEQ model assumes a fixed forward operator. In this work, we expand on DEQ models to include multicoil complex data for an improved multicoil DEQ (MCDEQ) reconstruction model that leverages a complex-valued UNET as the proximal operator. We also investigate the effect of training and testing with different sample patterns to study model stability under forward model changes, a known concern with DEQ models.5Methods

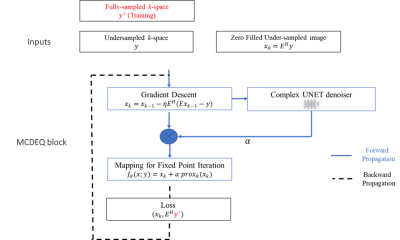

MCDEQ Architecture:The multicoil MRI reconstruction problem can be formulated as

$$\tilde{x}=\underset{x}{\operatorname{argmin}}\|E x-y\|_2+r(x) ; E=P F S$$

Where P is the sampling operator, F is the Fourier transform operator, S is the SENSE operator x is the image and y is the k-space measurements and r(x) is the regularizer. We replace r(x) with a complex-valued UNet to integrate complex MRI signal.

We implement the solution by taking the gradient descent and adding an extra learnable scaling parameter for the weights of the regularizer to mitigate the need for pretraining:

$$\begin{gathered}x_k=x_{k-1}-\eta E^H\left(E x_{k-1}-y\right) \\f_\theta(x ; y)=x_k+\alpha \operatorname{prox}_\theta\left(x_k\right)\end{gathered}$$

The MCDEQ model attempts to solve for a fixed point through fixed point iteration in the forward pass such that $$f_\theta(\bar{x} ; y)=\bar{x}$$. Anderson accelerated fixed point solver is used to accelerate the process of finding the fixed point.6 After finding the fixed point, the backpropagation is performed using implicit differentiation. The MCDEQ architecture is shown in Figure 1.

Dataset:

We used the 20-channel multicoil fastMRI7 brain dataset. The coil sensitivities were precomputed with the SigPy8 JSENSE recon. Ground truth images were generated with SENSE recon from fully sampled k-space data. The under-sampling masks were generated using a variable density Poisson-disc sampling pattern. (100/40) slices were used for training/validation. Batch size of 10 was used for training.

Denoiser/Regularizer:

We implemented a complex valued two layers deep UNET9 structure. Each layer contains complex convolution layer (complex inputs, real weights) followed by non-linear activation.

Comparison with MoDL:

A MoDL architecture with identical proximal denoiser was implemented with 5 unrolls and compared to MCDEQ trained for the same epoch with the same undersampling mask.

Results

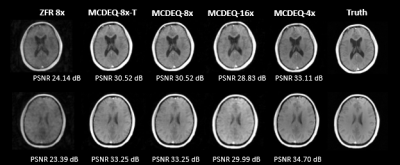

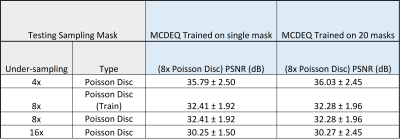

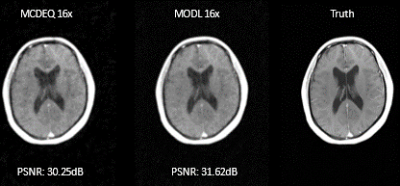

In the quantitative comparison, results show that the performance of the MCDEQ is similar to the MoDL architecture. Figure 2 depicts the images reconstructed by the two models in comparison to the ground truth.We experimented to find the optimal training strategy attempting to minimize the effects of model drift. The multicoil DEQ model was trained with a single masking pattern (undersampling factor= 8) and its performance was evaluated with various other undersampling masks. We subsequently trained the network with 20 different Poisson sampling patterns and assessed its performance. Table 1 shows the performance with different training regimes.

Figure 3 demonstrates the reconstructed images generated with MCDEQ trained on 20 different 8x times undersampling mask. MCDEQ-8x-T (evaluated on the same mask as training) show similar results to MCDEQ-8x suggesting the architecture is not susceptible to large model drifts.5

Discussion

Our results suggest proposed MCDEQ is insensitive to model drifts caused by coil sensitivity and sampling mask changes. Adding a scaling factor to the proximal operator in the architecture before computing the fixed point improved generalization, possibly by relying more on the forward model. DEQ performed similarly to MoDL while requiring less memory, but it required longer training time due to the numerical solution of the fixed point using Anderson acceleration. Further work is needed to evaluate this model's efficacy for large, 3D datasets where MoDL training isn't feasible due to modern GPU memory constraints.Conclusion

Adding a learnable scaling parameter to the proximal operator of the MCDEQ architecture leads to better generalization of training. The MCDEQ was not that sensitive to model drifting. you can add that MCDEQ was not very sensitive to model drifting.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the NIH (R01 DK125783) for supporting this study, as well as GE Healthcare which provides research support to the University of Wisconsin.References

1. Aggarwal HK, Mani MP, Jacob M. MoDL: Model Based Deep Learning Architecture for Inverse Problems. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2019;38(2):394-405. doi:10.1109/TMI.2018.2865356

2. Miller Z, Pirasteh A, Johnson KM. Memory Efficient Model Based Deep Learning Reconstructions for High Spatial Resolution 3D Non-Cartesian Acquisitions. May 2022. http://arxiv.org/abs/2204.13862. Accessed July 19, 2022.

3. Bai S, Kolter JZ, Koltun V. Deep Equilibrium Models. October 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1909.01377

4. Gilton D, Ongie G, Willett R. Deep Equilibrium Architectures for Inverse Problems in Imaging. June 2021. http://arxiv.org/abs/2102.07944. Accessed September 9, 2022.

5. Gilton D, Ongie G, Willett R. Model Adaptation for Inverse Problems in Imaging. April 2021. http://arxiv.org/abs/2012.00139. Accessed October 11, 2022.

6. Walker HF, Ni P. Anderson Acceleration for Fixed-Point Iterations. SIAM J Numer Anal. 2011;49(4):1715-1735. doi:10.1137/10078356X

7. Zbontar J, Knoll F, Sriram A, et al. fastMRI: An Open Dataset and Benchmarks for Accelerated MRI. December 2019. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1811.08839

8. Ong F, Martin J, Grissom W, et al. mikgroup/sigpy: Minor release to trigger Zenodo for DOI. January 2022. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5893788

9. Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In: Navab N, Hornegger J, Wells WM, Frangi AF, eds. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015. Vol 9351. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015:234-241. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28

Figures

Figure 2: Comparison to MoDL architecture. Similar levels of PSNR were achieved by the proposed MCDEQ when compared to MoDL. Further work to characterize memory efficiency of MCDEQ is ongoing. Both models were trained with 16x undersampling for the same no of epochs.