2924

Accelerate Single-Channel 3D MRI through Undersampling and Deep Neural Network Reconstruction1Laboratory of Biomedical Imaging and Signal Processing, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China, 2Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Image Reconstruction

3D MRI data contains more redundant information than 2D MRI data, which is favourable for reconstruction. However, deep learning reconstruction of 3D MRI data remains to be explored due to the computational burden that scales exponentially with spatial dimensions. This study presents a deep learning method to reconstruct single-channel 3D MRI data with uniform undersampling along two phase-encoding directions, in which conventional multi-channel parallel imaging methods are generally not applicable. The results demonstrate the robust reconstruction for single-channel 3D MRI data at high acceleration and in the presence of anomaly.Introduction

3D MRI data contains more redundant information than 2D MRI data, which is favourable for reconstruction. Conventional multi-channel parallel imaging methods (e.g., SENSE1 and GRAPPA2) have been extended to 3D MRI data by undersampling the k-space along two phase-encoding (PE) directions and exploiting the coil sensitivity variation in both spatial dimensions3,4. However, deep learning reconstruction on 3D MRI data is less explored due to the computational burden that scales exponentially with spatial dimensions. Thus, the majority of deep learning reconstructions focuses on 2D MRI data with only one phase-encoding direction5-7, preventing deep learning reconstructions from exploiting the redundancy of an intrinsically 3D physical object.In this study, we present a deep learning reconstruction method on single-channel 3D MRI data with uniform undersampling along two PE directions. Unlike prior studies that primarily reconstruct multi-channel 2D MRI data, the proposed method tackles single-channel data for scenarios such as portable and low-cost ultra-low-field MRI, where effective receiver coil arrays are not available8-11.

Methods

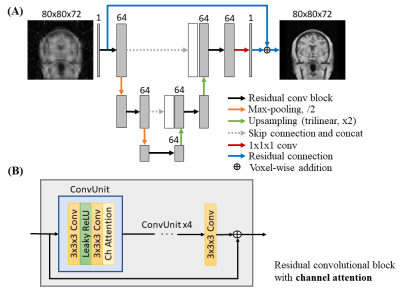

Model Architecture: A three-level 3D U-Net12 is adopted (Figure 1). In the contracting path, the down-sampling layers enable the model to extract multi-scale features by increasing the receptive field of convolutions. In the expansion path, the up-sampling layers allow the reconstructed volume to have the same spatial resolution as the input volume. Features in the contracting path are concatenated to the expansion path via skip connection to retain the high frequency information in the contracting path that is lost during down-sampling.At each level of the contracting and expansion paths, residual convolutional blocks with channel attention are adopted. 3D convolutions are used instead of 2D convolutions to better exploit the redundancy and continuity of a 3D physical object or structure. The residual connections in the block allow the proper training of a deeper model without suffering from the vanishing gradient problem13. Channel attention is used to capture the relation among channels of the same scale for effective feature extraction14.

The global residual connection, which sums the zero-filled input volume and the output volume of the model, is adopted to learn the residual aliasing artifact instead of a direct mapping from the aliased to alias-free volume.

Implementation details: The U-Net consisted of two down- and up-sampling layers, which were achieved by 3D convolutions of stride 2 with kernel size of 3x3x3 and trilinear interpolation of factor of 2 respectively. The number of channels was 64 for all convolutional layers for sustainable model training time. Leaky rectified linear unit (leaky ReLU) with negative slope of 0.1 was used as the non-linear activation function instead of ReLU. The network was trained with Adam optimizer with initial learning rate of 10-4, β1 = 0.9, and β2 = 0.999 for 350 epochs. The learning rate was reduced by 0.8 every 100 epochs. L1 loss function was selected. The training of the model took approximately 24 hours on a four V100 GPU server. Separate models were trained specifically for individual image contrast (e.g., T1w or T2w) for optimal performance.

Data Preparation: The 3D 0.7x0.7x0.7mm3 isotropic HCP S1200 dataset including T1w and T2w volumes from normal subjects were used15. To alleviate the GPU memory burden and to expedite the training in this study, image downsampling was performed to the magnitude data, resulting in 3x3x3mm3 isotropic data with matrix size of 80x80x72. The spatial volume was then Fourier transformed to k-space and retrospectively undersampled with acceleration R = 2x2 using 2D cartesian uniform sampling masks, plus 16x16 central k-space lines. Zero-filled magnitude data without phase information was treated as the model input. For each contrast, 1000 MRI volumes were split in ratio of 8:1:1 for training, validation, and testing, respectively.

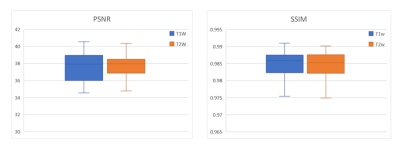

SSIM, PSNR and NRMSE were used to quantitatively evaluate the reconstructed images. The proposed method was also evaluated with data containing anomaly unseen in the training dataset.

Results

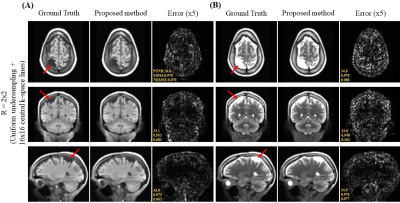

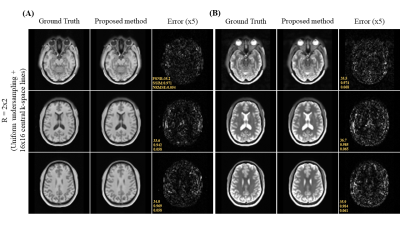

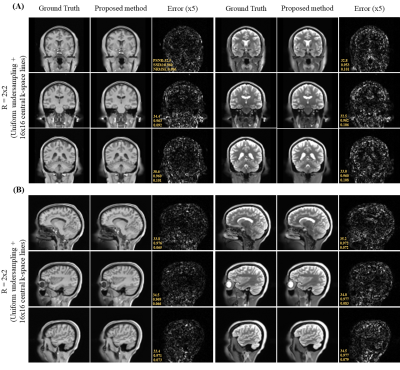

Figure 2 shows the axial view of the proposed deep learning reconstruction on single-channel 3D T1w and T2w data at R=2x2 (effective R=3.46). Coronal and sagittal views of the proposed method with the same effective acceleration were also shown (Figure 3). No apparent image residual artifact was observed in different slices and orientations. The proposed method reconstructed with high structural fidelity. Figure 4 shows the multi-orientation views of the proposed deep learning reconstruction of images containing brain structural lesion or anomaly to illustrate the robustness of the proposed method on MRI data that was unseen during training. Figure 5 shows the box plot of PSNR and SSIM across 30 test datasets to demonstrate the stability of the proposed method among different subjects.Discussion and Conclusion

We present a 3D deep learning reconstruction method for cartesian uniform undersampling of single-channel 3D MRI data, where existing multi-channel parallel imaging reconstruction methods are not applicable. The results demonstrated robust reconstruction without apparent residual artifact at high acceleration and in the presence of unseen brain structural anomaly. The proposed method offers a promising approach to accelerated single-channel 3D MRI. Further evaluations are needed to validate the proposed method.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Hong Kong Research Grant Council (R7003-19F, HKU17112120, HKU17127121 and HKU17127022 to E.X.W., and HKU17103819, HKU17104020 and HKU17127021 to A.T.L.L.), Lam Woo Foundation, and Guangdong Key Technologies for AD Diagnostic and Treatment of Brain (2018B030336001) to E.X.W..References

1. K. P. Pruessmann, M. Weiger, M. B. Scheidegger, and P. Boesiger, “SENSE: Sensitivity encoding for fast MRI,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 952–962, 1999.

2. M. A. Griswold et al., “Generalized Autocalibrating Partially Parallel Acquisitions (GRAPPA),” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 47, no. 6, pp. 1202–1210, 2002.

3. M. Weiger, K. P. Pruessmann, and P. Boesiger, “2D SENSE for faster 3D MRI,” Magn. Reson. Mater. Physics, Biol. Med., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 10–19, 2002.

4. M. Blaimer et al., “2D-GRAPPA-operator for faster 3D parallel MRI,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 56, no. 6, pp. 1359–1364, 2006.

5. M. Hyun, H. P. Kim, S. M. Lee, S. Lee, and J. K. Seo, “Deep learning for undersampled MRI reconstruction,” Phys. Med. Biol., vol. 63, no. 13, 2018.

6. K. Hammernik et al., “Learning a variational network for reconstruction of accelerated MRI data,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 79, no. 6, pp. 3055–3071, 2018.

7. B. Zhu, J. Z. Liu, S. F. Cauley, B. R. Rosen, and M. S. Rosen, “Image reconstruction by domain-transform manifold learning,” Nature, vol. 555, no. 7697, pp. 487–492, 2018.

8. J. P. Marques, F. F. J. Simonis, and A. G. Webb, “Low-field MRI: An MR physics perspective,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 1528–1542, Jun. 2019.

9. L. L. Wald, P. C. McDaniel, T. Witzel, J. P. Stockmann, and C. Z. Cooley, “Low-cost and portable MRI,” J. Magn. Reson. Imaging, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 686–696, Sep. 2020.

10. C. Z. Cooley et al., “A portable scanner for magnetic resonance imaging of the brain,” Nat. Biomed. Eng., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 229–239, 2021.

11. Y. Liu et al., “A low-cost and shielding-free ultra-low-field brain MRI scanner,” Nat. Commun., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2021.

12. J. Cai, L. Lu, Z. Zhang, F. Xing, L. Yang, and Q. Yin, “3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation,” Med. Image Comput. Comput. Interv., pp. 424–432, 2016.

13. K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun, “Deep residual learning for image recognition,” Proc. IEEE Comput. Soc. Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit., pp. 770–778, 2016.

14. S. Woo, J. Park, J. Y. Lee, and I. S. Kweon, “CBAM: Convolutional block attention module,” in Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 2018, vol. 11211 LNCS, pp. 3–19.

15. Van Essen, D.C., et al: The wu-minn human connectome project: an overview. Neuroimage 80, 62-79, 2013.

Figures

Fig. 1. (A) Overall architecture of the 3D neural network of the proposed method with zero-filled magnitude data as the input. (B) Detailed illustration of the residual convolutional block with channel attention. 3D convolutions of kernel size 3x3x3 and leaky rectified linear unit (leaky ReLU) are used. Channel attention learns the inter-channel relationship of features from preceding convolution. Residual connection performs voxel-wise addition between input and output features.

Fig. 3. (A) Coronal and (B) sagittal views of the 3D single-channel ground-truth image (i.e., from fully sampled k-space data) and reconstructed T1w and T2w images using the proposed method with uniform undersampling R=2x2 plus 16x16 central k-space lines. The proposed method demonstrated robust image reconstruction without apparent residual artifact resulted from uniformly undersampled k-space data under single-channel scenario.