2908

Navigator-based slice tracking for liver pCASL using spin-echo EPI acquisition

Ke Zhang1, Simon M.F. Triphan1, Oliver Sedlaczek1,2, Christian Ziener2, Hans-Ulrich Kauczor1, Heinz-Peter Schlemmer2, and Felix T. Kurz2

1Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany, 2Department of Radiology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

1Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Heidelberg University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany, 2Department of Radiology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Pulse Sequence Design, Arterial spin labelling

Liver perfusion is an important physiological parameter in health and disease (1,2). In the measurement of liver perfusion using arterial spin labelling (ASL), respiratory motion is a major challenge. In this study, respiratory motion information is acquired from a projection signal and used to adjust the position of the excited slice in real time. The feasibility of free-breathing multi-slice liver perfusion imaging using spin-echo EPI based pseudo-continuous ASL (pCASL) with navigator-based slice tracking method is investigated.PURPOSE

To apply the navigator-based slice tracking method to prospectively compensate the respiratory motion for liver pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling (pCASL) using spin-echo EPI (SE-EPI) acquisition.METHODS

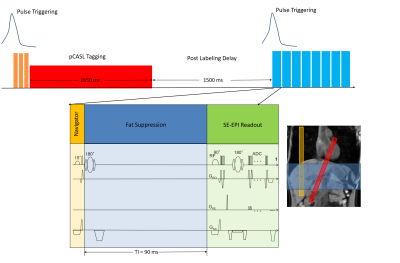

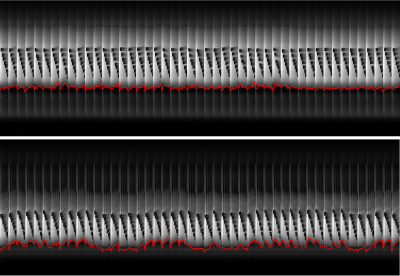

Measurements were performed using an 18-channel body and spine receive RF coil on a 1.5T scanner (Aera, Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany). A single gradient-echo slice selection and projection readout at the location of the diaphragm along the inferior-superior (IS) direction was acquired as a navigator. Navigator acquisition and fat suppression were inserted before each transverse imaging slice of the readouts of 2D spin-echo EPI based pCASL (NAV- pCASL) sequence (Fig. 1), with 50 measurements including 32 training navigators at the beginning of measurements obtained in 5.8 minutes. Sequence parameters were as follows: TE =12 ms, FOV=400×240 mm3, partial Fourier = 6/8, in-plane iPAT factor=3, matrix size=120×72×8, resolution=3.3×3.3×8 mm3, slice gap = 4 mm, labeling duration = 1650 ms, postlabeling delay (PLD) =2000 ms, TR = 7000 ms, TI for SPAIR (SPectral Attenuated Inversion Recovery) fat suppression=90 ms, FOVnav = 200 mm, resnav = 64, Flip anglenav = 15º, TRnav=4.22ms. The labeling pulse train and readout were triggered by the pulse signal and played out only during the systolic period. Hepatic blood flow was selectively tagged using a tagging plane placed at the portal vein. As a reference, pCASL scans using a timed breathing protocol were performed, referred to as “Breathing Holding” (BH). The breath-hold extended over consecutive labeling, PLD, and 2D SE-EPI phases. Subjects were instructed to take one deep breath during the following time span until the TR of 7000 ms was reached and go back into the exhaled breath-hold as soon as possible. Since the repetition time was set to 7000 ms, 2740 ms were available in each repetition for comfortable inhalation and exhalation. For comparison, pCASL scans without breath-holding and navigator-based motion correction were also performed, referred to as “Free Breathing” (FB).Before motion analysis, the interleaved navigator signals during image acquisition were Fourier transformed and truncated to exclude RF saturation along IS direction from the SE-EPI readout (Fig. 2). The position for this truncation was calculated based on peaks fitted from the averaged training navigator and the peaks from the first 32 interleaved navigators. The diaphragm position was derived by calculating the phase difference of the interleaved navigator signals at each acquisition after Fourier transform and truncation. The unwrapped data from different coils were then combined by using coil clustering (3) based on the first 32 interleaved navigators. The motion information was then directly sent back to the sequence and slice positioning was adjusted in real-time. This motion analysis and real-time feedback was performed on the scanner, implemented in ICE (Image calculation environment, Siemens Healthineers AG, Erlangen, Germany).

RESULTS

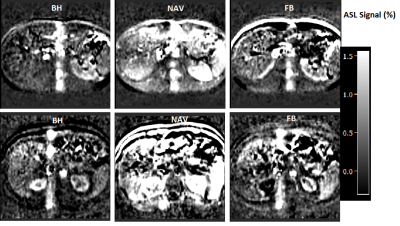

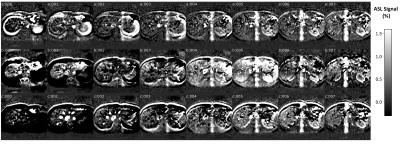

The respiratory motion from navigator signals could be precisely calculated (Fig. 2) and slice positioning was changed in real-time based on the motion information. The subtracted perfusion weighted maps show higher perfusion from NAV-pCASL than from BH and FB-pCASL (Fig. 3). More detailed structure in the perfusion weighted maps could be observed in the NAV-pCASL case (Fig. 3, 4).CONCLUSION

This study demonstrates the feasibility of navigator-based slice tracking technique in liver pCASL using SE-EPI readout.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), 507778062.References

1. Pandharipande PV, Krinsky GA, Rusinek H, Lee VS. Perfusion imaging of the liver: Current challenges and future goals. Radiology 2005;234(3):661-673.

2. Kim SH, Kamaya A, Willmann JK. CT Perfusion of the Liver: Principles and Applications in Oncology. Radiology 2014;272(2):321-343.

3. Zhang T, Cheng JY, Chen YX, Nishimura DG, Pauly JM, Vasanawala SS. Robust Self-Navigated Body MRI Using Dense Coil Arrays. Magn Reson Med 2016;76(1):197-205.

Figures

Fig 1. A single gradient-echo slice selection and projection readout at

the location of the diaphragm along the IS direction is applied as a navigator.

Navigator acquisition and fat suppression were inserted before each transverse

imaging slice of the SE-EPI sequence. The labeling pulse

train and readout were triggered by the pulse signal and performed during systolic period. Blood flow was tagged using a tagging

plane (red) placed at the portal vein. The navigator was placed perpendicular

to the diaphragm (yellow) and the imaging volume was placed to cover the

kidneys (blue).

Fig 2. Respiration motion and motion correction in two heathy subjects

(top down). Signal of navigator shows abdomen motion with respiration. The

calculated motion information are overlaid (red curve). Note the signal

saturation in the navigator signal caused by imaging slices.

Fig 3. Liver pCASL results from two healthy subjects (top down).

Normalized ASL signals (defined as the magnetization difference between the

signals in the selective and nonselective cases, relative to the relaxed

magnetization of the erector spinae muscle) from breath-hold (BH); navigator based (NAV)

and free breathing (FB)-pCASL are listed in different column.

Fig 4. Multi-slice kidney perfusion images from a represented healthy

subject. The 8 slices acquired normalized ASL signals from BH (a); NAV (b) and

FB (c)-pCASL are listed.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2908