2877

Behavioural and functional assessment of mice inner ear after chronic exposure to an ultra-high static magnetic field of 11.7T or 17.2T.1University of Paris-Saclay, CEA, CNRS, BAOBAB, NeuroSpin, Gif-sur-Yvette, France, 2University of Paris-Saclay, CNRS, NeuroPSI, Saclay, France

Synopsis

Keywords: Bioeffects & Magnetic Fields, Animals

High static magnetic (B0) fields are known to induce a transient disturbance of the inner ear. Recently a study demonstrated long-term behavioural effects in mice chronically exposed to a B0 field of 16.4T. In the current study, mice underwent chronic B0 exposure at 11.7T or 17.2T and longitudinally performed behavioural tests over the study. An auditory brainstem response (ABR) test was performed at the end of the full exposure period to assess inner ear properties. Despite the transient disturbance of mice inner ear observed immediately after B0 exposure, no short-term or long-term alteration was detected with behavioural or ABR tests.Introduction

The transitory disturbance of the inner ear after exposure to a high static magnetic (B0) field has been previously reported, with subjects experiencing dizziness, vertigo, nystagmus and / or nausea [1-3] and rodents displaying a transient (< 5 minutes) rotating behaviour [4]. Physiological mechanisms behind these observations are however not yet fully understood [5-7]. In 2021, a study reported long-term behavioural effects in mice chronically exposed to a B0 field of 16.4T, suggesting a long-term impairment of mice vestibular system in these extreme conditions [8].The current study thus focuses on the detection of a potential impairment of mice inner ear during and / or after chronic exposure to an ultra-high B0 field of 11.7T or 17.2T. Behavioural tests were longitudinally conducted throughout the study to assess mice balance and motor coordination in order to detect potential vestibular deficits. An auditory brainstem response (ABR) test was performed at the end of the study to detect more precisely any long-term impairment of the inner ear function.

Methods

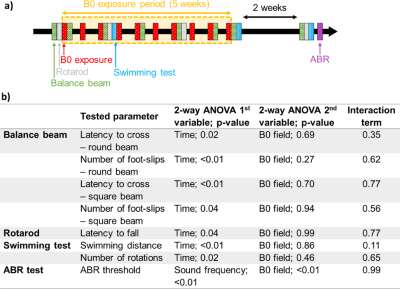

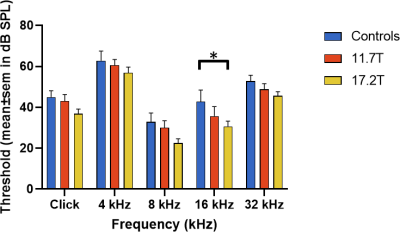

Experiments were performed on C57BL/6 mice (Janvier, Saint Isle, France), aged 9 weeks at the beginning of the study. Mice were divided into three groups of N=8 (4 males and 4 females). The first group was used as a control, the second group was exposed in a 11.7T MRI scanner (BioSpec, Bruker BioSpin, Ettlingen, Germany), and the third group in a 17.2T scanner (BioSpec, Bruker BioSpin). Mice underwent ten B0 exposure sessions of 2h each evenly distributed over a period of 5 weeks, resulting in a total of 20h exposure per mice (Figure 1a). No MR sequence was played during these sessions. During B0 exposure, mice were anaesthetised (1% isoflurane) and placed in plastic tubes (Falcon 50 mL) at the centre of the scanners, half of them being oriented parallel to B0 and the other half being oriented antiparallel. Control mice were also anaesthetised and placed in plastic tubes.The behavioural tests conducted longitudinally during the study (Figure 1a) included balance beam walk tests with two different beams (total of 8 sessions), rotarod tests (4 sessions) and motor swimming tests (3 sessions). ABR tests were performed under light anaesthesia (1% isoflurane) at the end of all behavioural tests (i.e. three weeks after the last B0 exposure). The ABR test provides an insight of cochlea properties by measuring the lowest sound pressure level (SPL), called ABR threshold, that generates an evoked potential in the brainstem when presenting an auditory stimulus played at a given frequency.

After a verification of normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests, data were analyzed with two-way repeated measures ANOVAs followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test using Prism 9.4.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA) in order to compare the results of the three groups of mice. Values are reported in Figure 1b.

Results

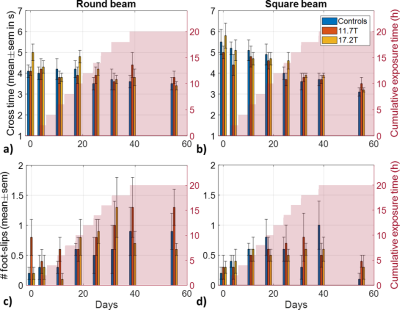

After awaking following B0 exposures at 11.7T and 17.2T, mice exposed parallel to B0 were rotating counter-clockwise, while mice exposed anti-parallel to B0 were rotating clockwise. This effect was no longer observable on a maximum of 2 min after the mice were taken out of the scanners.Balance beam test (Figure 2): for the two beams, mice showed a concomitant decreasing latency to cross the beams and increasing number of foot-slips over time. No differences with B0 field were observed, and the interaction terms were not significant.

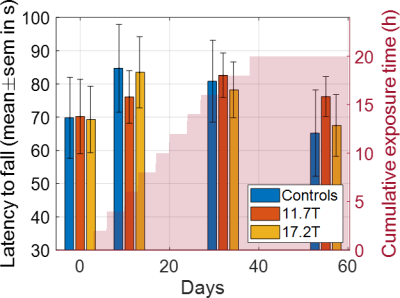

Rotarod test (Figure 3): the latency to fall off the rod showed a significant variation over time, but no significant difference neither for B0 field nor for the interaction term was found.

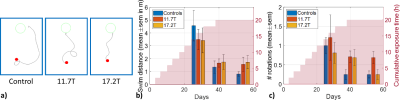

Swimming test (Figure 4): the mice did on average less than one rotation when swimming to the platform in the tank, and the number of rotations decreased over time, likely caused by the decrease of the swimming distance. No difference with B0 field was observed either for the swimming distance or for the number of rotations. The corresponding interaction terms were also not significant.

Multiple comparison tests did not show any significant difference between the three groups of mice at any time point for any behavioural test. As such, no motor coordination or balance deficit were detected with the behavioural tests.

ABR test (Figure 5): there was a significant variation of ABR thresholds with B0 field. Multiple comparisons showed that only the 16 kHz stimulus threshold was significantly higher for control mice compared to mice exposed at 17.2T (p-value = 0.03). Although the higher thresholds of control mice could not be explained, these results suggest that no long-term impairment of inner ear function and hair cells properties resulted from chronic B0 exposure.

Conclusion

Immediately after exposure to an ultra-high B0 field, mice experienced a transient disturbance of the vestibular system, demonstrated by their temporary rotating behaviour when they returned in their home cage. However, on the day following B0 exposures, no alteration of their inner ear could be detected with behavioural tests sensitive to balance and motor coordination, even after chronic exposure (i.e. 20h of B0 exposure distributed over a period of 5 weeks). Last but not least, no long-term impairment of mice inner ear properties could be detected in the weeks following the last B0 exposure session, as assessed with behavioural and ABR tests.Acknowledgements

This work received financial support from the European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under grant agreement no. 885876 (AROMA).References

[1] Patel, Mita, Robert A. Williamsom, Samuel Dorevitch, and Susan Buchanan. "Pilot study investigating the effect of the static magnetic field from a 9.4-T MRI on the vestibular system." Journal of occupational and environmental medicine (2008): 576-583.

[2] Heinrich, Angela, Anne Szostek, Patric Meyer, Frauke Nees, Jaane Rauschenberg, Jens Gröbner, Maria Gilles et al. "Cognition and sensation in very high static magnetic fields: a randomized case-crossover study with different field strengths." Radiology 266, no. 1 (2013): 236-245.

[3] Uwano, Ikuko, Tsuyoshi Metoki, Fusako Sendai, Ryoko Yoshida, Kohsuke Kudo, Fumio Yamashita, Satomi Higuchi et al. "Assessment of sensations experienced by subjects during MR imaging examination at 7T." Magnetic Resonance in Medical Sciences 14, no. 1 (2015): 35-41.

[4] Houpt, Thomas A., Bumsup Kwon, Charles E. Houpt, Bryan Neth, and James C. Smith. "Orientation within a high magnetic field determines swimming direction and laterality of c-Fos induction in mice." American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 305, no. 7 (2013): R793-R803.

[5] Glover, Paul M., Ian Cavin, W. Qian, R. Bowtell, and Penelope A. Gowland. "Magnetic‐field‐induced vertigo: A theoretical and experimental investigation." Bioelectromagnetics: Journal of the Bioelectromagnetics Society, The Society for Physical Regulation in Biology and Medicine, The European Bioelectromagnetics Association 28, no. 5 (2007): 349-361.

[6] Antunes, Andre, P. M. Glover, Yan Li, O. S. Mian, and B. L. Day. "Magnetic field effects on the vestibular system: calculation of the pressure on the cupula due to ionic current-induced Lorentz force." Physics in Medicine & Biology 57, no. 14 (2012): 4477.

[7] Ward, Bryan K., Dale C. Roberts, Charles C. Della Santina, John P. Carey, and David S. Zee. "Vestibular stimulation by magnetic fields." Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1343, no. 1 (2015): 69-79.

[8] Tkáč, I., Benneyworth, M. A., Nichols‐Meade, T., Steuer, E. L., Larson, S. N., Metzger, G. J., & Uğurbil, K. (2021). "Long‐term behavioral effects observed in mice chronically exposed to static ultra‐high magnetic fields". Magnetic resonance in medicine, 86(3), 1544-1559.

Figures