2843

Altered resting-state connectivity in nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients late stage post-radiotherapy: an Independent Component Analysis

Xiaohan Song1 and Lijun Wang1

1The First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China

1The First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical University, Dalian, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Head & Neck/ENT, fMRI (resting state)

Radiotherapy is the primary treatment modality for patients with Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. However, radiotherapy in the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma will also cause neurocognitive impairment. Previous studies mostly focused on the changes of brain structure in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma caused by radiotherapy, but it was reported that there were changes in brain network connectivity before the brain structure was abnormal. So, the purpose of thestudy was to investigate network-level functional connectivity alternations late stage post radiation therapy in Nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients using independent component analysis of rs-fMRI.Synopsis

The purpose of the present study was to investigate network-level functional connectivity (FC) alternations late stage post radiation therapy (RT) in Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) patients using independent component analysis (ICA) of rs-fMRI.Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) is the primary treatment modality for patients with Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) [1]. Traditionally, according to time of completion of RT, neurological side-effects induced by RT can be described in terms of acute (few days to few weeks), early delayed (1–6 months), and late delayed injury (> 6 months) [2]. Acute and early delayed radiation effects are transient and reversible with modern therapeutic standards; yet late delayed radiation effects (≥6 months post-irradiation) remain a significant risk, resulting in progressive cognitive impairment[3]. However, the mechanism of how the irradiation can induce the network-level functional connectivity (FC) disruption remains an open question. The application of the independent component analysis (ICA) of rs-fMRI may provide additional insight into RT-related pathophysiology. The purpose of this study was to investigate network-level FC alternations late post RT in NPC patients.Material and Methods

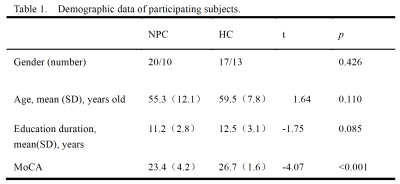

30 volunteers and 30 patients with NPC were recruited with informed consent acquired from each subject (Table 1). All patients were scanned using a 3.0T whole body imaging system (GE HDxt, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with an 8-channel head coil. Sagittal 3D T1-weighted images were acquired using a brain volume (BRAVO) sequence with the following parameters: TR)/ TE)= 8.8/3.1ms, TI = 400ms, matrix =256 × 256; FOV)= 256 × 256mm, FA= 12°, slice thickness = 1.0 mm with no gap; 184 sagittal slices. The rs-fMRI data were obtained using a gradient echo single-shot echo planar imaging sequence with the following parameters: TR/TE = 2000/30 ms; slice thickness = 3 mm, 1 mm gap; FOV = 220 × 220 mm2; matrix = 64 × 64; FA = 90°; 36 interleaved transverse slices; 180 volumes. Data preprocessing was carried out using the Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI (DPABI] [4] .ICA was performed using a group ICA (GICA) program for fMRI data (GIFT) (http://icatb.sourceforge.net/, version 2.0a). We performed GICA 100 times and obtained 34 independent components that were auto estimated by the GICA software. Fifteen meaningful components were identified as RSNs via visual inspection. The individual level components were obtained from back-reconstruction, and the intra-network FC was represented by the z-value of each voxel, which reflects the degree to which the time series. The differences in the intra network FC between the two groups were compared using SPM8 with two sample t-tests. Age, gender and educational level were included as covariates to exclude the possible influences of these parameters. The significance level for the group differences was set to a threshold of P < 0.05 in DPABI ( Alphasim correction).

We extracted the time-courses of each RSN from the ICA procedure, which was normalized with the Fisher r-to-z transformation. Then, the time-courses of each pair of the 15 RSNs were used to calculate the temporal correlation, namely functional network connectivity (FNC). The two-sample t-test was used to determine which pairs of RSNs were significantly different (P < 0.05) in the FNC between the NPC and control groups. Age, gender, and educational level were included as covariates.

Results

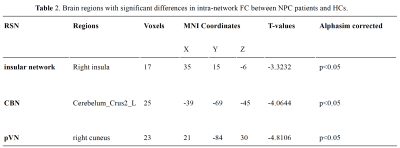

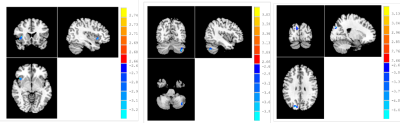

Significant group differences (P < 0.05, AlphaSim corrected) were detected in multiple brain regions (Fig. 1 and Table 2). NPC patients exhibited a significant decrease of intra-network FC in the right insula of the insular network, the right cuneus of the occipital pole visual network, as well as the left Cerebelum Crus2 of the cerebellum network.Compared with the healthy controls, NPC subjects showed significantly (P< 0.05, uncorrected) increased FNCs between the salience network(SN) and the sensorimotor network(SMN) and between the left executive control network(ECN) and the insular network; while the FNCs between the left FPN and the posterior visual network(pVN) and between the SN and the anterior default mode network(aDMN) were decreased in NPC subjects (P < 0.05, uncorrected). However, none of these differences can survive after Bonferroni correction (P < 0.05).

Discussion

Quantification of network-level FC of normal appearing brain tissue after RT may help us understand the physiologic processes late post RT in NPC patients. Our results showed that both the intra-network (pVN, insular network and CBN) and several inter-network FCs significantly altered late post-RT in NPC patients. ICA of rs-fMRI seemed to provide additional insight into RT-related pathophysiology late post RT in NPC patients than the clinical conventional MRI.Conclusion

Combining the analysis of intra- and inter- network FC provided new insights into the radiation-induced functional impairments in NPC patient late post-RT. This result may has the potential to advance the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in NPC patients in the future.Acknowledgements

Thanks for the guidances, especially my tutor Professor Wang Lijun, from the Department of Radiology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical UniversityReferences

1.Xu C, Zhang LH, Chen YP, Liu X, Zhou GQ, Lin AH, Sun Y, Ma J. Chemoradiotherapy Versus Radiotherapy Alone in Stage II Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: A Systemic Review and Meta-analysis of 2138 Patients. J Cancer. 2017;8(2):287-297. 2.Soussain C, Ricard D, Fike JR, Mazeron JJ, Psimaras D, Delattre JY. CNS complications of radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Lancet. 2009;374(9701):1639-51. 3.Greene-Schloesser D, Moore E, Robbins ME. Molecular pathways: radiation-induced cognitive impairment. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(9):2294-300. 4. Yan CG, Wang XD, Zuo XN, Zang YF. DPABI: Data Processing & Analysis for (Resting-State) Brain Imaging. Neuroinformatics. 2016;14(3):339-51.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2843