2820

4D flow MRI reveals cerebrovascular changes in early Alzheimer’s disease1Faculty of Health & Environmental Studies, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand, 2Department of Medicine, University of Otago, Christchurch, New Zealand, 3NZ Brain Research Institute, Christchurch, New Zealand, 4School of Psychology, Speech and Hearing, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 5Department of Psychology, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 6Centre for Advanced MRI, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Velocity & Flow

Currently 50 million people suffer from Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, yet treatment options are limited. A growing focus on the contribution of cerebrovascular (CV) health presents new possible targets for treatment. We investigated novel CV imaging markers using 4D flow MRI in a total of 43 participants with mild cognitive impairment, early AD and controls. Both the MCI and AD group had significantly reduced mean blood flow in the larger vessels of the Circle of Willis. A significantly increased pulsatility index (indicative of poorer vessel compliance) was found in the AD group compared to controls.

INTRODUCTION

There is mounting evidence that cerebrovascular (CV) dysfunction is influential in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia.1–6 However, functional properties of CV health, that can be measured in vivo, such as blood flow, vessel compliance/stiffness and wall shear stress are understudied in their relation to cognitive decline, especially during development and progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Novel imaging metrics of CV function are needed, as they may identify specific targets for new interventions. 4D flow MRI7 has recently become a reliable tool to capture complex vascular anatomy and hemodynamics in the heart and is emerging as a promising technique to study the cerebral vasculature.8,9 In this study we measured multiple haemodynamic markers in the brain, in participants with MCI and early AD.METHODS:

MRI - Scans were performed on a 3T MRI (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a prototype 4D flow sequence, employing a 3D phase-contrast acquisition, retrospective cardiac gating, velocity encoding (venc) = 90cm/s, number of phases/bins per cardiac cycle = 20, FoV = 210 × 168 × 60 mm, centred on the Circle of Willis (CoW) and acquired voxel size 1mm3.Participants – Participants were recruited from the Dementia Prevention Research Clinic in Auckland, New Zealand. Participants were classified following a multi-disciplinary assessment and extensive neuropsychological testing into the following three groups: cognitively normal (CN), MCI and early probable AD.

Image processing – Data were processed using 4D Flow Demonstrator V2.3 (Siemens AG, Erlangen, Germany) and Circle cardiovascular imaging cvi42 V5.14 (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., Calgary, Canada). Eleven vessel “segments” were placed proximal and distal to the CoW.8 At these positions we evaluated mean blood flow (MBF), net flow volume (NFV), pulsatility index (PI: max-min/mean flow). Wall shear stress (WSS) was qualitatively and quantitatively evaluated in a subset of participants (n=5). The anatomical variation of the CoW was categorised into one of four groups according to the presence of both pre-communicating branches of the anterior and posterior cerebral arteries which were “textbook” second and third groups were right or left posterior and anterior cerebral hypoplasia respectively. All other variations were classified as “other”.

RESULTS:

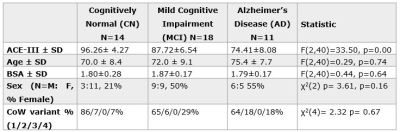

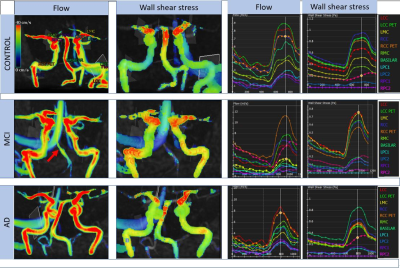

Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-III, was statistically different across the groups and in all subsequent pair-wise comparisons. No significant between-group differences were found for age, body surface area (BSA), sex and the proportion of CoW variants across the groups (see tabulated data in Figure 1).Figure 2 presents representative cases from each group. Flow and wall shear stress visualisations (columns 1 and 2) highlight only subtle differences in flow and pressure patterns, except when vessels have weak filling (MCI case). Plots of flow and wall shear stress across the cardiac cycle (columns 3 and 4) show, as expected peaks in flow and pressure values during systole. A greater range of flow (max-min) compared to the mean flow, is seen in MCI and AD cases, yielding an increased pulsatility index and indicative of increased vessel stiffness.

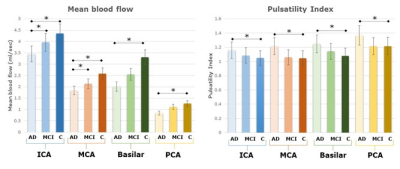

Group results (Figure 3), show significantly reduced mean flow across all vessels in the AD group compared to controls, while the MCI group had a significant mean flow reduction in the larger vessels (i.e., the ICA and MCA) only. The pulsatility index was significantly higher in the AD group compared to controls, but no significant changes in the MCI group compared to the controls were found in any vessels. Net flow volume (results not plotted) was also significantly reduced in all vessel segments in the AD group and in all vessels in the MCI group, except the ICA.

Average WSS, measured in a subset of participants appears to be associated with MBF and PI in the carotids. Furthermore, increased WSS appears to be linked to the presence of CoW anatomical variation in the middle cerebral and basilar arteries.

DISCUSSION:

Vasomotor impairment has been suggested to affect beta amyloid clearance which would contribute to the pathogenesis of AD.10 Arterial wall and endothelial integrity are essential for the vasodilatory response.11 A reduction in vascular elasticity would reduce the peripheral pumping effect and reduce mean blood flow and net flow volumes to brain tissue. It has also been suggested that wall shear stress variations leads to multiple pathologies as microaneurysms and contribute to endothelial function integrity.12 Thus, studying these markers is essential to understand both the physiology and pathology that affects brain tissue in those with cognitive impairment. Anatomical vascular variation contributes to altered flow measurements, and therefore characterising flow behavior in these variations in larger studies is essential. Recruitment for the current study is ongoing.CONCLUSION:

Our cross-sectional pilot results of reduced mean blood flow in MCI and early AD, and increased pulsitility in early AD, suggest diminished blood flow is an early indicator of vascular dysfunction that may lead to poorer vessel compliance on the AD trajectory.Acknowledgements

This work is funded by Brain Research New Zealand - Rangahau Roro Aotearoa, Centre of Research Excellence, New Zealand. CM is supported by the Freemasons Foundation, New Zealand. We would like to acknowledge all the staff at Dementia Prevention Research Clinic in Auckland. We thank Siemens Healthcare for the provision of the 4D flow prototype sequence and Dr. Kieran O’Brien for advice on its use.References

1. Arvanitakis, Z., Capuano, A. W., Leurgans, S. E., Bennett, D. A. & Schneider, J. A. Relation of cerebral vessel disease to Alzheimer’s disease dementia and cognitive function in elderly people: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet. Neurology 15, 934–943 (2016).

2. Toledo, J. B. et al. Contribution of cerebrovascular disease in autopsy confirmed neurodegenerative disease cases in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre. Brain : a journal of neurology 136, 2697–2706 (2013).

3. Vargas-González, J.-C. & Hachinski, V. Insidious Cerebrovascular Disease—The Uncool Iceberg. JAMA Neurology 77, 155–156 (2020).

4. Iturria-Medina, Y., Sotero, R. C., Toussaint, P. J., Mateos-Pérez, J. M. & Evans, A. C. Early role of vascular dysregulation on late-onset Alzheimer’s disease based on multifactorial data-driven analysis. Nature Communications 7, 11934 (2016).

5. Hachinski, V. Dementia: Paradigm shifting into high gear. Alzheimers Dement 15, 985–994 (2019).

6. van der Flier, W. M. et al. Vascular cognitive impairment. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 4, 1–16 (2018).

7. Stankovic, Z., Allen, B. D., Garcia, J., Jarvis, K. B. & Markl, M. 4D flow imaging with MRI. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 4, 173–192 (2014).

8. Rivera-Rivera, L. A. et al. 4D flow MRI for intracranial hemodynamics assessment in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 36, 1718–1730 (2016).

9. Wåhlin, A., Eklund, A. & Malm, J. 4D flow MRI hemodynamic biomarkers for cerebrovascular diseases. Journal of Internal Medicine 291, 115–127 (2022).

10. Morris, A. W. J., Carare, R. O., Schreiber, S. & Hawkes, C. A. The Cerebrovascular Basement Membrane: Role in the Clearance of β-amyloid and Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 6, 251–251 (2014).

11. Di Marco, L. Y., Farkas, E., Martin, C., Venneri, A. & Frangi, A. F. Is Vasomotion in Cerebral Arteries Impaired in Alzheimer’s Disease? J Alzheimers Dis 46, 35–53 (2015).

12. Carr, J. M. J. R. & Ainslie, P. N. Shearing the brain. Journal of Applied Physiology 129, 599–602 (2020).

Figures

Figure 1. Neuropsychological, demographic and anatomical summary of participants. ANOVA result comparing Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-III (ACE-III) age, body surface area (BSA), and a χ2 test comparing frequency distributions of sex and CoW variants across groups, is reported in the last column.

Figure 2. Representative examples of AD, MCI and control cases. Noticeable is weaker flow in the basilar artery (red arrow) in the MCI case that also has a CoW variation in anatomy. Levels: LCC: left internal carotid; LCC PET: left internal carotid (petrous level) LMC: left middle cerebral; RCC: right internal carotid; RCC PET: right internal carotid (petrous level) RMC: right middle cerebral; Basilar: Basilar artery before bifurcation; LPC: left posterior cerebral; RPC: right posterior cerebral.

Figure 3. Haemodynamic parameter group results. Left: Mean blood flow for each group in the internal carotid (ICA), middle cerebral artery (MCA), Basilar and posterior cerebral artery (PCA). Error bars are ± 1 S.D Significant pair-wise differences (p<0.05) are marked by an asterix (*). Right: Pulsatility Index for the same subjects.