2812

On the prediction of cognitive impairment trajectories from anatomical MRI in ADNI: preliminary results1Methods of Plasticity Research, Department of Psychology, University of Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland, 2Neuroscience Center Zurich (ZNZ), UZH & ETHZ, Zürich, Switzerland, 3University Research Priority Program (URPP) Dynamic of Healthy Aging, University of Zurich, Zürich, Switzerland

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Neurodegeneration

We predict yearly differences in MMSE and CDR-SOB using data from the ADNI cohort ranging from five years before to five years after the imaging session. We show that models that use embeddings from a deep-learning model trained to predict brain-age or models that use bilateral hippocampi, amygdalae, and accumbens perform approximately the same as models that use baseline cognitive scores as inputs. This has potential ramifications for both clinical machine learning applications and the neurobiology of cognitive decline. In future work, we will finetune the deep-learning model and substantially increase the sample size.Introduction

Cognitive decline is a common consequence of healthy and pathological aging. Severity varies greatly between individuals, ranging from unnoticeable to potentially debilitating. These cognitive changes can be assessed by the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), two widely used tools for the clinical assessment and staging of cognitive impairment. Imagine-derived phenotypes obtained from neuroimaging and other biomarkers are increasingly being used to identify individuals at risk for cognitive decline and dementia. Our previous work1 shows that several neuroanatomical markers are predictive of cognitive decline in the OASIS-3 study, in addition to clinical, demographic and neuropsychometric information. However, the identification of neuroanatomical markers that are sensitive to early changes in cognition is challenging. In this study, we aim to predict past and future changes in cognition, assessed by the CDR and MMSE, using structural MRI in a large longitudinal imaging cohort of older adults from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).Methods

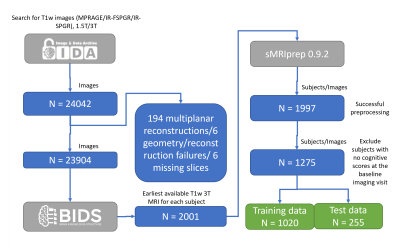

Data used in the preparation of this abstract were obtained from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early Alzheimer's disease (AD). See www.adni-info.org.We selected the earliest available T1w 3T MRI from each subject in ADNI. In total, data from 1997 ADNI subjects were retrieved and successfully processed with sMRIPrep. A flow diagram detailing the steps to obtain the final sample is depicted in Figure 1.

Results included in this manuscript come from preprocessing performed using sMRIPprep2,3 (RRID:SCR_016216), which is based on Nipype 1.8.1 (RRID:SCR_002502). The sMRIprep 0.9.2 standard workflow includes N4 intensity non-uniformity correction (ANTs 2.3.3), skull-stripping (ANTs "antsBrainExtraction.sh" Nipype implementation, using OASIS30ANTs as target template), "FAST" tissue segmentation (FSL 6.0.5.1, RRID:SCR_002823), "recon-all" brain surfaces reconstruction (FreeSurfer 7.2.0, RRID:SCR_001847), and brain mask refinement using the method to reconcile ANTs- and FreeSurfer-derived Mindboggle cortical gray-matter segmentations (Mindboggle, RRID:SCR_002438).

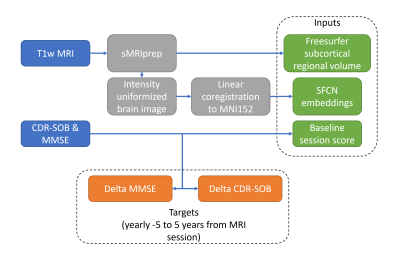

The visit with both CDR-SOB and MMSE and within one year of the baseline MRI session was designated as the baseline clinical visit. This choice is due to the mismatch of dates between clinical and imaging sessions. Outcomes were defined as the difference from current to baseline MMSE and CDR-SOB scores, ranging from 5 years in the past to 5 years in the future.

Intensity normalized brain volumes were extracted from the Freesurfer output of sMRIPrep processed baseline MRI and linearly coregistered to the MNI152Lin template with FSL. Resulting normalized volumes were center cropped to a 160x192x160 voxel volume. These volumes were fed to the pretrained brain-age SFCN model4. We fine-tuned the last layer on ADNI, which is a common practice in transfer learning. We substituted the last layer of the SFCN model with linear layers predicting continuous outcomes. This is equivalent to independent linear models, one for each outcome and each time point. 1020 subjects were used for training and 255 subjects for validation. Figure 2 summarizes the selection of input and output variables. We additionally estimated three baseline linear models predicting the yearly cognitive impairment from : baseline cognitive scores, subcortical volumes from regions identified with high predictive importance for future cognitive decline in our previous work in the OASIS-3 dataset1, and a naïve average over the training data. All models were estimated using Python 3.10.

Results

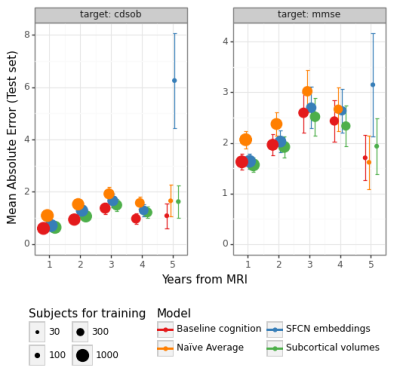

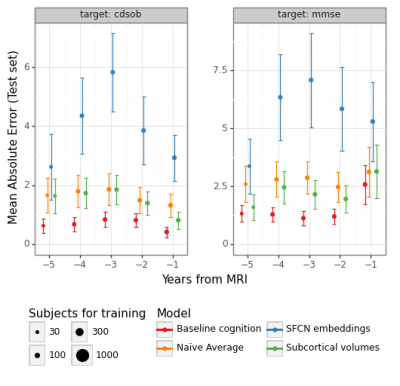

The predictions for MMSE and CDRSOB one and two years after baseline are shown in Figure 3.The absolute error for predictions across time points is shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, for years after and prior to the baseline imaging session, respectively.

Discussion

SFCN embeddings do not substantially predict cognitive change better than linear models trained on subcortical volumes or baseline cognitive scores (Fig-3). One possible explanation is that the SFCN model was trained to predict age in subjects aged from 42 to 82 years, whereas our ADNI subset covers subjects aged from 50 to 95 years at their imaging visit, and have on average increased risk for cognitive decline. We are working on finetuning the whole SFCN model on the ADNI dataset.As in our previous work1, we found that baseline cognitive scores are strong predictors of cognitive change, although MRI-derived features can attain similar performance (Fig-4). This suggests that MRI-derived features capture approximately the same level of performance regarding cognitive trajectories as clinical scores. Comparing the models with a naïve average model, however, shows that predictive performance is not substantial. This might happen due to low sample sizes, which is particularly evident in the prediction of cognitive differences prior to the baseline MRI session. We are currently working on augmenting the dataset by processing additional sessions from the ADNI dataset, which should homogenize the sample sizes for different years.

We conclude from our preliminary results that no evidence of a substantial improvement in prediction performance is found when using MRI-derived features over clinical scores. This can have important implications for the use of MRI-derived features in clinical practice, particularly on the use of MRI-derived features for the prediction of cognitive trajectories. We will explore on the neuroscientific implications of these results in future work.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation [10001C_197480] at the University of Zurich. Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health ( www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

References

1. Vieira BH, Liem F, Dadi K, Engemann DA, Gramfort A, Bellec P, et al. Predicting future cognitive decline from non-brain and multimodal brain imaging data in healthy and pathological aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2022 Oct 1;118:55–65.

2. Esteban O, Markiewicz CJ, Goncalves M, Provins C, Kent JD, DuPre E, et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI [Internet]. Zenodo; 2022 [cited 2022 Nov 9]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/record/7117719

3. Esteban O, Markiewicz CJ, Blair RW, Moodie CA, Isik AI, Erramuzpe A, et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat Methods. 2019 Jan;16(1):111–6.

4. Peng H, Gong W, Beckmann CF, Vedaldi A, Smith SM. Accurate brain age prediction with lightweight deep neural networks. Med Image Anal. 2021 Feb 1;68:101871.

Figures