2809

Microstructural neurodegeneration of the entorhinal-hippocampus pathway in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: ex vivo 11.7T MRI and histology1Department of Radiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2Department of Pathology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Microstructure

Conventional neuroimaging biomarkers for the neurodegeneration of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) are not sensitive enough to detect neurodegenerative alterations in preclinical AD individuals. We aimed to examine microstructural neurodegeneration of the entorhinal-hippocampus pathway during the pathological process of AD. Our ex vivo comparative study of 11.7T MRI and histology successfully visualized microstructural neurodegeneration of the entorhinal-hippocampus pathway in preclinical AD brain tissues. In a future study, we aim to translate the findings from ex vivo 11.7T MRI and histology into in vivo MRI clinical research for preclinical AD individuals.INTRODUCTION

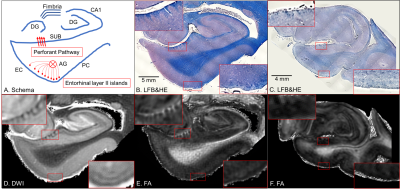

Neurons in layer II of the entorhinal cortex cluster to form neuronal-rich islands1, from which projection fibers converge to form the angular bundle that reaches the subiculum and connects to the hippocampus as the perforant pathway2 (entorhinal-hippocampus pathway or EHP, Figure 1A). In Alzheimer’s disease (AD), memory loss becomes irreversible due to neurodegeneration of the EHP3. However, whether such microstructural neurodegeneration is seen in the preclinical stage of AD remains to be elucidated. In this study, we aim to investigate how microstructural neurodegeneration of the EHP progresses during the pathological process of the AD continuum. We hypothesized that cyto- and myeloarchitectonic features of the EHP would be altered in preclinical AD.MATERIALS AND METHODS

Brain specimen and histological preparationDe-identified postmortem brain specimens of the left cerebral hemisphere from a cognitively unimpaired individual without AD pathological changes (non-AD), a cognitively unimpaired individual with AD pathological changes (preclinical AD), and a demented individual with AD pathological changes (AD dementia) were provided by the Brain Resource Center, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. The brain specimens were fixed in 10% formaldehyde for more than two weeks, then sectioned into 10 mm thick coronal slabs. Following MRI scans, the brain tissues were embedded in paraffin blocks, cut into 10 µm thick sections at 200 μm intervals, and stained using Luxol fast blue with hematoxylin and eosin (LFB&HE) and amyloid- and tau-immunostaining for histological verification.

Image acquisition

Diffusion MRI was acquired using 11.7T NMR spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA, USA). A single-channel 30 mm Bruker volume coil was used for both radio frequency transmission and reception. Diffusion-weighted gradient and spin echo sequence with navigator phase correction was applied to scan the ex vivo brain tissues4. The scan parameters were: echo time = 24, 34, 44, and 55 ms; repetition time = 0.7 s; two signal averages; two b0 images; and ten diffusion directions with a b-value of 2300 s/mm2. The field of view was 40 × 30 × 16 mm3 and the zero-filled matrix size was 320 × 240 × 128, resulting in the final resolution of 125 μm isotropic. The total scan time was 40 hours per scan.

Image processing and analysis

DtiStudio software5 was used for the tensor calculation and creation of diffusion tensor images. Diffusion-weighted image (DWI) was generated by averaging diffusion MRI along isotropically-distributed diffusion directions. Fractional anisotropy (FA) values of the entorhinal laminae were measured in each brain tissue. The EHP was constructed by deterministic tractography6 as a tract connecting the entorhinal layer II and the dentate gyrus. An FA threshold of 0.1, an angle threshold of 60 degrees, and a minimum length of five pixels were applied.

Statistics

This study included the ex vivo MRI and histological data from three de-identified postmortem individuals. Therefore, we did not perform inferential statistics but descriptive statistics and graphical displays.

RESULTS

Anatomical identificationThe entorhinal layer II islands and perforant pathway showed blue chromophilic contrasts in LFB&HE, which were clearly visible in non-AD (Figure 1B), whereas they are not visible in AD dementia (Figure 1C). These cyto- and myeloarchitectonic features could be observed on ex vivo 11.7T MRI. In non-AD, DWI displays dark striate intensities for fibers of the perforant pathway and bright patchy intensities for the entorhinal layer II islands (Figure 1D). The FA map displays bright striates for fibers of the perforant pathway and a bright lamina in the entorhinal layer II (Figure 1E). In contrast, ex vivo images in AD dementia reveal the demise of the entorhinal layer II islands and perforant path fibers (Figure 1F).

Quantitative analysis

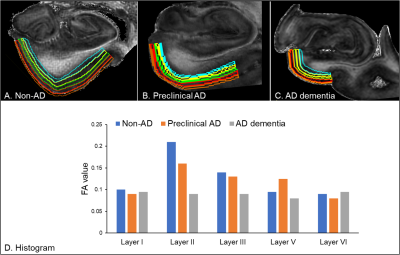

At 125 μm isotropic resolution, laminar contrasts were seen within the entorhinal cortex. The RoiEditor software delineated the boundary of the cortical substructures, extracting FA values in each cortical lamina (Layer I–IV) from the non-AD (Figure 2A), preclinical AD (Figure 2B), and AD dementia (Figure 2C). We found that the FA value of the entorhinal layer II was the highest among the entorhinal laminae in non-AD and preclinical AD, whereas the FA values were homogenously low in AD dementia (Figure 2D). Note that layer IV, which corresponds to the internal granular layer, is indiscernible in the entorhinal cortex.

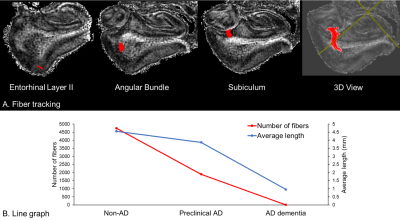

Tract Reconstruction

The perforant path fibers were clearly visualized in non-AD and preclinical AD (Figure 3A), but not in AD dementia. The number and average length of fibers became decreased during the pathological process of the AD continuum (non-AD > preclinical AD > AD dementia).

DISCUSSION

Conventional neuroimaging biomarkers for the neurodegeneration of AD are not sensitive enough to detect neurodegenerative alterations during the preclinical stage of AD7. Given the clinical and pathological significance of the EHP to the earliest AD pathogenesis2, 8-10, establishing a methodology for quantification of these microstructures is a priority issue for the development of a novel neurodegenerative biomarker for preclinical AD. Our results showed that the FA value of the entorhinal layer II will be a promising measure for a highly sensitive and focal neurodegenerative biomarker.CONCLUSION

We successfully visualized microstructural neurodegeneration of the EHP in the AD continuum ex vivo. In a future study, we aim to translate the findings from ex vivo 11.7T MRI and histology into in vivo MRI clinical research.Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Richman Family Precision Medicine Center of Excellence in Alzheimer's Disease including significant contributions from the Richman Family Foundation, the Rick Sharp Alzheimer’s Foundation, the Sharp Family Foundation and others. SM is a founder and KOi is a consultant for “AnatomyWorks” and “Corporate-M.” This arrangement is being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies. The authors thank the Brain Resource Center for providing the brain specimens and Mary McAllister for English-language editing.References

1. Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991;82:239-259.

2. Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Kromer LJ, Damasio AR. Perforant pathway changes and the memory impairment of Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol 1986;20:472-481.

3. Hyman BT, Van Hoesen GW, Damasio AR, Barnes CL. Alzheimer's disease: cell-specific pathology isolates the hippocampal formation. Science 1984;225:1168-1170.

4. Aggarwal M, Mori S, Shimogori T, et al. Three-dimensional diffusion tensor microimaging for anatomical characterization of the mouse brain. Magn Reson Med 2010;64:249-261.

5. Jiang H, van Zijl PC, Kim J, et al. DtiStudio: resource program for diffusion tensor computation and fiber bundle tracking. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2006;81:106-116.

6. Mori S, Crain BJ, Chacko VP, van Zijl PC. Three-dimensional tracking of axonal projections in the brain by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 1999;45:265-269.

7. Jack CR, Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2018;14:535-562.

8. Gómez-Isla T, Price JL, McKeel DW, Jr., et al. Profound loss of layer II entorhinal cortex neurons occurs in very mild Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 1996;16:4491-4500.

9. Price JL, Ko AI, Wade MJ, et al. Neuron number in the entorhinal cortex and CA1 in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2001;58:1395-1402.

10. Yassa MA, Muftuler LT, Stark CE. Ultrahigh-resolution microstructural diffusion tensor imaging reveals perforant path degradation in aged humans in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:12687-12691.

Figures