2808

Hippocampal sLASER 1H-MRS in cognitively unimpaired elderly: Associations with APOE4, CSF p-tau181 and MR morphometry1Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 3Department of Radiology, Cochin Hospital, Paris, France, 4Department of Psychiatry, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 5Department of Biostatistics, New York University School of Global Public Health, New York, NY, United States, 6Department of Radiology, Columbia University, New York, NY, United States, 7Department of Neurology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 8Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, Department of Radiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Gray Matter, Hippocampus

The hippocampus, a vulnerable structure in Alzheimer’s disease progression, is one of the most challenging brain structures for 1H-MRS applications. To examine whether hippocampal metabolic dysfunction in cognitively normal elderly may contribute to disease pathology, we used a validated long-TE sLASER sequence to minimize macromolecular signal contamination and chemical shift displacement errors. We tested whether, after adjusting for age, metabolites were associated with APOE4 genotype, a risk factor for amyloid accumulation; and CSF p-tau181 and left hippocampal volume, indicators of tau burden and neurodegeneration, respectively. The main result was a statistically significant direct correlation between Glx and CSF p-tau181.Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) studies using established imaging, plasma, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-based biomarkers have shown that molecular changes begin years before symptom onset1, but mechanisms underlying the hallmark pathological aggregation of amyloid and tau are still unknown. To address this from a 1H-MRS standpoint, studies have used conventional PRESS sequences in cognitively unimpaired populations to examine metabolic dysfunction associated with AD development and progression in otherwise normal-appearing tissue in the posterior cingulate2-5. However, the hippocampus, one of the earliest affected regions in AD6, is rarely interrogated by 1H-MRS because it is situated in a location with poor B0 homogeneity and large susceptibility effects. Here, we applied a recently validated7 long-TE sLASER sequence, which, with its high bandwidth adiabatic pulses, reduces chemical shift displacement errors (CSDE) inherent to PRESS; and, with its long-TE, minimizes macromolecular contribution to the background signal, improving metabolite quantification, especially of the Glx pseudo-singlet. The voxel was placed in the left hippocampus, as it exhibits greater vulnerability to atrophy and disease progression compared to the right8, to measure choline (Cho), creatine (Cr), glutamate plus glutamine (Glx), myo-inositol (mI), and N-acetylaspartate (NAA). We hypothesized (i) elevated mI and reduced NAA in apolipoprotein E4 carriers (APOE4+) vs. non-carriers (APOE4-), where APOE4+ confers risk for amyloid burden9; (ii) reduced NAA with higher CSF p-tau181, an indicator of tau burden1; and (iii) reduced NAA with lower left hippocampal volume, a measure of atrophy1.Materials and Methods

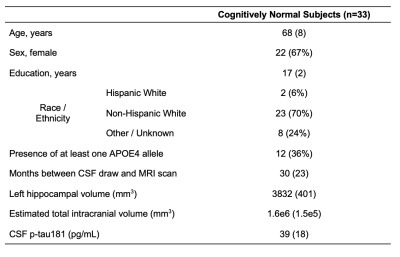

Thirty-three cognitively unimpaired elderly (22 female, 68±8 years old) were scanned at 3T (MAGNETOM Prisma, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with a 20-channel transmit-receive head coil. The protocol (Fig.1A) included an MPRAGE for anatomical localization, a FLAIR for radiological assessment, and a sLASER7 for 1H-MRS in the left hippocampus, using a 3.4 mL voxel (Fig.1B). GOIA-W refocusing pulses with 15 and 20 kHz bandwidths were applied to minimize CSDE7. Simulations had been performed to select an optimal long-TE (120 ms) that significantly reduced the macromolecular signal, while also retaining high SNR for the J-coupled mI and Glx metabolites. FID-A10 and INSPECTOR11 were used for spectral processing and analysis (Fig.1C). Absolute metabolite concentrations (mM) were calculated using the measured water signal after accounting for the different water and metabolite relaxation times in gray and white matter.Importantly, concentrations were also adjusted for voxel tissue and CSF fractions. To obtain those, as well as overall tissue volume measures, each subject’s MPRAGE was processed through FreeSurfer v6.0.0 segmentation12. Left hippocampal volumes were extracted and normalized by each subject’s respective estimated total intracranial volume, to correct for variations in head size13.

CSF p-tau181 levels, collected 30±23 months from the imaging exam, were only available for 23 subjects.

APOE4+ were defined as having at least one E4 allele; and APOE4- as having no E4 allele.

Pearson’s correlations with and without age-adjustment were used to examine associations between metabolite concentrations and CSF p-tau181 levels or left hippocampal volume, followed by jackknife sensitivity analyses to evaluate reproducibility. An age-adjusted ANCOVA was used to assess group differences (APOE4+ vs. APOE4-) across metabolite concentrations. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

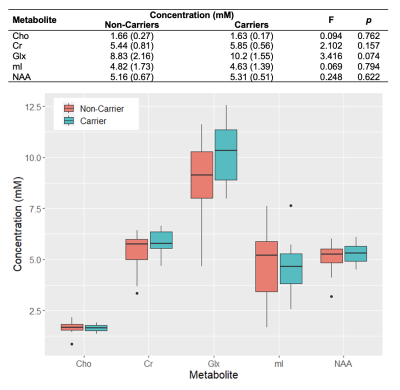

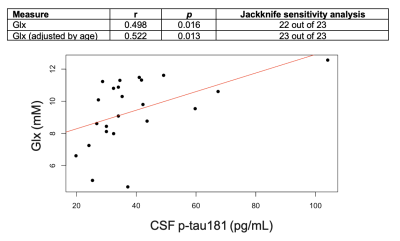

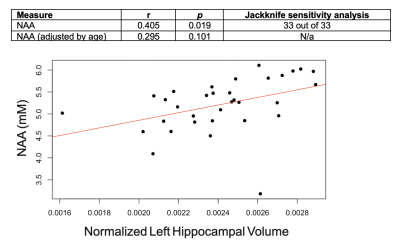

Population characteristics are compiled in Table 1. We observed a direct correlation between Glx and CSF p-tau181 that was reproducible in jackknife analysis (r=0.52, p=0.01) (Fig.2), and an indirect correlation between NAA and left hippocampal volume that was no longer significant after age-adjustment (Fig.3). We found no group differences in metabolite levels, but note a statistical trend (p=0.07) for higher Glx in APOE4+ vs. APOE4- individuals (Fig.4).Discussion

Elevated left hippocampal Glx correlated with elevated CSF p-tau181, a marker of greater global neurofibrillary tangle load14. Glx is a composite signal of glutamate and glutamine, metabolites involved in glutamatergic transmission. Higher Glx may indicate glutamate accumulation at the synapse, which can trigger increased calcium influx and excitotoxicity, and consequently activate protein kinases responsible for tau hyperphosphorylation15.Based on a previous study that found elevated posterior cingulate mI in APOE4+3, we hypothesized similar findings in the left hippocampus, as it is functionally connected to the posterior cingulate within the default-mode-network16. Genotype, however, did not mediate any metabolite differences in this region.

As hypothesized, lower left hippocampal NAA was associated with lower left hippocampal volume, but not after adjusting for age. Correlations with age yielded indirect relationships with both left hippocampal NAA (r=-0.42, p=0.02) and volume (r=-0.37, p=0.03), suggesting that cellular mechanisms related to aging, and not necessarily AD pathology, may contribute to the reduced neuronal density and/or volume loss observed here. Autopsy studies have shown age-related loss of hippocampal neurons17, and imaging studies have shown age-related reductions in hippocampal volume18. Furthermore, a recent whole-brain 1H-MRS study in 207 cognitively unimpaired adults (20-90 years old) showed an age-related decline of NAA19.

Our long-TE sLASER 1H-MRS approach allowed us to optimize metabolite quantification from the left hippocampus by minimizing both CSDE and macromolecular contamination, and improving detection of multiplet species (Glx, mI). Moreover, we report absolute concentrations, which can be directly interpreted. Our preliminary results show that, in cognitively unimpaired individuals, synaptic dysfunction (Glx) may be linked to tau pathogenesis. Importantly, we are working to complete CSF p-tau181 collection and analysis for all subjects to increase the statistical power of this association.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a pilot grant to Dr. Kirov (P30AG008051) from the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (P30AG066512) at New York University Langone Health.References

1 Jack, C. R., Jr. et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association 14, 535-562 (2018). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.0182 Kara, F. et al. 1H MR spectroscopy biomarkers of neuronal and synaptic function are associated with tau deposition in cognitively unimpaired older adults. Neurobiol Aging 112, 16-26 (2022).

3 Voevodskaya, O. et al. Myo-inositol changes precede amyloid pathology and relate to APOE genotype in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 86, 1754-1761 (2016).

4 Kantarci, K. et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy, β-amyloid load, and cognition in a population-based sample of cognitively normal older adults. Neurology 77, 951-958 (2011).

5 Nedelska, Z. et al. <sup>1</sup>H-MRS metabolites and rate of β-amyloid accumulation on serial PET in clinically normal adults. Neurology 89, 1391-1399 (2017). https://doi.org:10.1212/wnl.0000000000004421

6 Pennanen, C. et al. Hippocampus and entorhinal cortex in mild cognitive impairment and early AD. Neurobiol Aging 25, 303-310 (2004). https://doi.org:10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00084-8

7 Gajdosik, M. et al. Hippocampal single-voxel MR spectroscopy with a long echo time at 3 T using semi-LASER sequence. NMR Biomed 34, e4538 (2021). https://doi.org:10.1002/nbm.4538

8 Sarica, A. et al. MRI Asymmetry Index of Hippocampal Subfields Increases Through the Continuum From the Mild Cognitive Impairment to the Alzheimer's Disease. Front Neurosci 12, 576 (2018). https://doi.org:10.3389/fnins.2018.00576

9 Baek, M. S. et al. Effect of APOE epsilon4 genotype on amyloid-beta and tau accumulation in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther 12, 140 (2020). https://doi.org:10.1186/s13195-020-00710-6

10 Simpson, R., Devenyi, G. A., Jezzard, P., Hennessy, T. J. & Near, J. Advanced processing and simulation of MRS data using the FID appliance (FID‐A)—an open source, MATLAB‐based toolkit. Magnetic resonance in medicine 77, 23-33 (2017).

11 Gajdosik, M., Landheer, K., Swanberg, K. M. & Juchem, C. INSPECTOR: free software for magnetic resonance spectroscopy data inspection, processing, simulation and analysis. Sci Rep 11, 2094 (2021). https://doi.org:10.1038/s41598-021-81193-9

12 Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62, 774-781 (2012). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.01.021

13 Voevodskaya, O. et al. The effects of intracranial volume adjustment approaches on multiple regional MRI volumes in healthy aging and Alzheimer's disease. Front Aging Neurosci 6, 264 (2014). https://doi.org:10.3389/fnagi.2014.00264

14 Bridel, C. et al. Associating Alzheimer's disease pathology with its cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers. Brain (2022). https://doi.org:10.1093/brain/awac013

15 Bukke, V. N. et al. The Dual Role of Glutamatergic Neurotransmission in Alzheimer's Disease: From Pathophysiology to Pharmacotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 21 (2020). https://doi.org:10.3390/ijms21207452

16 Greicius, M. D., Srivastava, G., Reiss, A. L. & Menon, V. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer's disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101, 4637-4642 (2004). https://doi.org:10.1073/pnas.0308627101

17 Piguet, O. et al. White matter loss in healthy ageing: a postmortem analysis. Neurobiol Aging 30, 1288-1295 (2009). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.10.015

18 Barnes, J. et al. A meta-analysis of hippocampal atrophy rates in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 30, 1711-1723 (2009). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.01.010

19 Kirov, II et al. Global brain volume and N-acetyl-aspartate decline over seven decades of normal aging. Neurobiol Aging 98, 42-51 (2021). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.10.024

Figures

Table 1. Participant characteristics. Data are expressed as mean (and standard deviation) or number of participants (and percentage), as appropriate.

Figure 1. Imaging protocol (A). Left hippocampal voxel placement (B), overlaid on sagittal (left), coronal (middle), and axial (right) MPRAGE slices from a single subject. A spectrum (black) acquired from one subject, along with its fitted function (red) and residual signal (gray) (C). Quantified metabolites are labeled by their peaks: Cho, choline; Cr, creatine; Glx, glutamate plus glutamine; mI, myo-inositol; NAA, N-acetylaspartate.

Figure 2. Associations between left hippocampal Glx and CSF p-tau181, with and without age-adjustment. Presented are Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r), p-values (p), and results of the jackknife sensitivity analyses.

Figure 3. Associations between left hippocampal NAA and left hippocampal volume (normalized to estimated total intracranial volume), with and without age-adjustment. Presented are Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r), p-values (p), and the result of the jackknife sensitivity analysis for the statistically significant finding only.