2805

Non-invasive MRI of Blood-Cerebrospinal-Fluid-Barrier Function: A Novel Functional Biomarker of Alzheimer's Disease Pathology1UCL Centre for Advanced Biomedical Imaging, Division of Medicine, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Champalimaud Foundation, Lisbon, Portugal, 3Neuroradiological Academic Unit, Department of Brain Repair and Rehabilitation,, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, United Kingdom, 4Dementia Research Centre, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, United Kingdom, 5Wellcome Centre for Human Neuroimaging, UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, London, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Arterial spin labelling

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterised by many pathophysiological changes, such as the accumulation of amyloid-β. The clearing of detrimental agents, including amyloid-β proteins, from brain tissue is linked to the function of choroid plexus (CP) or blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB).This study investigates for the first time BCSFB function using non-invasive ASL-based methods in a mouse model of AD. Significantly higher values of total BCSFB-mediated water delivery in AD mice relative to controls were observed as early as 8 weeks of age, and a possible (though currently non-significant) correlation with behavioural tests was identified.Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by many pathophysiological changes, such as accumulation of amyloid-β and formation of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles, that precede brain atrophy, even by decades. The clearing of detrimental agents, including amyloid-β proteins, from brain tissue is linked to the function of choroid plexus (CP) or blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB) [1,2].Recently, a novel ASL technique was proposed to quantify the BCSFB function, in-vivo, without any exogenous tracers, with initial characterisation in young and aged mice [3,4]. The methodology captures rates of BCSFB-mediated water delivery intro ventricular CSF, as a surrogate measure of BCSFB function, by acquiring the ASL images at a very long echo time.

Here we hypothesise that such non-invasive measures of BCSFB function represent a novel and sensitive biomarker of AD pathology. To this end, we performed longitudinal, multiparametric MRI measurements and behavioural testing, in the B6;129-3xTg mouse model of AD, which recapitulates both amyloid and tau pathology.

Methods

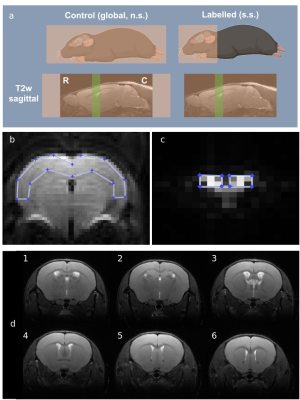

All experiments were preapproved by the competent institutional and national authorities and were carried out in accordance with European Directive 2010/63.Animals: Female 3xTg AD mice (B6;129-Tg(APPSwe,tauP301L)1Lfa) and normal controls (NC) (B6129SF2/J) were imaged at 8, 14, 20 and 32 weeks of age (NTG,8=7, NNC,8=7; NTG,14=5, NNC,14=7; NTG,20=3, NNC,20=6; NTG,32=5, NNC,32=7). ASL data was acquired on a 9.4T Bruker Biospec scanner equipped with a 86 mm volume transmit coil and a 4-element array reception cryocoil. Briefly, mice were induced with 5% isofluorane and maintained at 2%, while monitoring breathing rate and temperature.

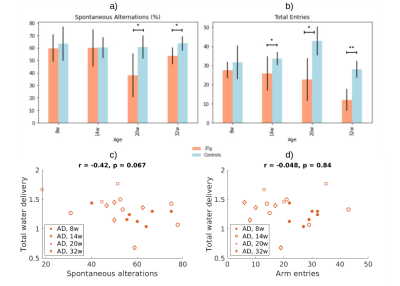

Y-maze test: Before scanning, the working memory of the animals was probed using the Y-maze behaviour test, following the protocol in [4]. The Y-maze is an apparatus that consists of three identical arms. Each animal was placed in one arm of the maze, and the movement recorded for 8 minutes [6]. The number of arm entries and spontaneous alterations were manually calculated from the video recording.

MRI acquisitions: BCSFB-ASL datasets were acquired using FAIR-EPI (Figure 1a) with TE=220ms, 10 repetitions, slice thickness=2.4 mm, FOV = 20mm x 20mm, matrix = 32x32, 7 inversion times (TI = [200, 750, 1500, 2750, 4000, 5000, 6000 ms]), and constant recovery time (TRec = 12000 ms). Standard ASL datasets for mapping cerebral blood flow (CBF) were also acquired with TE=20ms, 5 repetitions, FOV = 10mm x 14mm, matrix = 40x56, 7 inversion times (TI = [200, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, 3000, 4000 ms].

MRI data analysis: The total BCSFB-ASL signal in the lateral ventricles was obtained from 12 voxels (Figure 1b) [4]. Similarly, for standard-ASL images (TE=20 ms), an ROI was positioned across the brain cortex (Figure 1c). The mean subtracted ASL signal values (ΔM) within the ROIs were fit to the relevant Buxton kinetic model [5], incorporating individual T1 and M0 estimated from inversion recovery fittings[4]. For BCSFB-ASL, M0 is normalised to subject-wise ventricular volume calculated from structural images (Figure 1d). The fitted parameters include cortical perfusion (TE=20 ms), and rates of BCSFB-mediated water delivery (TE=220 ms). Multiplying the average output water delivery by the functional ROI volume returns the total water delivery rate to the LV.

Results

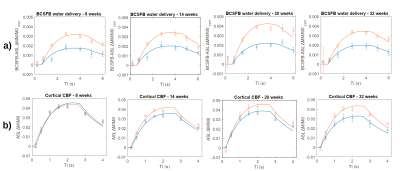

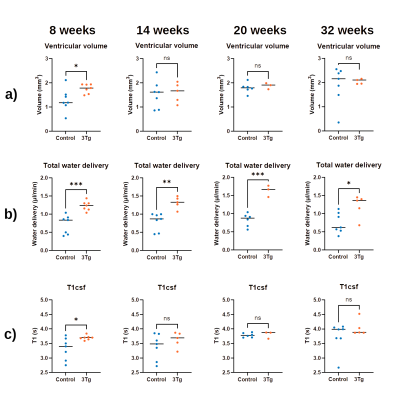

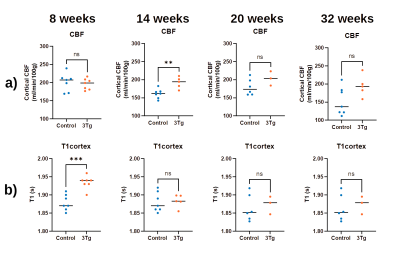

Figure 2 presents the a) BCSFB and b) cortical CBF kinetic ASL curves for the two groups of animals at different ages. The BCSFB curves for 3xTg animals are above the curves for WT animals for all ages, while the CBF curves are different only from 14 weeks onwards. This results in model parameter differences, shown in Figure 3 and 4, respectively. Total BCSFB-mediated water delivery is significantly higher in 3xTg mice of all ages (at least 50% higher compared to controls), and at 8 weeks, there are also significant differences in T1CSF and ventricular volume. For CBF-ASL, there are significant differences in CBF at 14 weeks (CBF 3xTg > CBF controls) and cortical T1 at 8 weeks of age (T1ctx 3xTg > T1ctx controls).The behaviour results (Figure 5a,b) show significant differences between groups starting from 14 weeks for the number of arm entries and from 20 weeks for the number of spontaneous alterations. We also observed a probable negative correlation between BCSFB-mediated water delivery and the number of spontaneous alterations (r=-0.42, p=0.067) (Figure 5c,d).

Discussion

We have investigated for the first time BCSFB function using non-invasive ASL-based methods in a mouse model of AD. Differences relative to controls were observed as early as 8 weeks of age, and a possible (though currently non-significant) correlation with behavioural tests was identified. The increased BCSFB-mediated water delivery values are not explained by differences in ventricular volumes, thus possibly reflecting a hyperactivity of BCSFB function in 3xTg animals. Parameters derived from standard ASL measurements also showed slightly higher values compared to controls, but were significantly different only at 14 weeks, and showed no correlation with behaviour. Limitations: the statistical power varies for different ages and we work towards increasing the N.Conclusion

Total water delivery across BCSFB measured by ASL appears to be a promising biomarker for detecting early derangement in Alzheimer’s disease.Acknowledgements

AI and RC are supported by ”la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434) and European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 847648, fellowship code CF/BQ/PI20/11760029. CP was supported by the Alzheimer’s Society (AS-PhD-18-006). JW was supported by the Wellcome Trust/Royal Society (grant no. 204624/Z/16/Z).References

[1] Engelhardt B, Sorokin L. The blood-brain and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers: functionand dysfunction. Semin Immunopathol. 2009 Nov;31(4):497-511. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0177-0. Epub 2009 Sep 25. PMID: 19779720.

[2] Solár, P. et al. Choroid plexus and the blood–cerebrospinal fluid barrier in disease. Fluids Barriers CNS 17,35 (2020) ttps://doi.org/10.1186/s12987-020-00196-2

[3] Evans, P.G. et al. Non-Invasive MRI of Blood–Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier Function. Nat Commun 11, 2081 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16002-4

[4] Perera, C. et al, Pharmacological MRI with Simultaneous Measurement of Cerebral Perfusion and Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier Function using Interleaved Echo-Time Arterial Spin Labelling. NeuroImage 238:118270, (2021). 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118270

[5] Buxton, R. et al A General Kinetic Model for Quantitative Perfusion Imaging with Arterial Spin Labeling. Magn Reson Med 383-396 (1998).

[6] Kraeuter AK, Guest PC, Sarnyai Z. The Y-Maze for Assessment of Spatial Working and Reference Memory in Mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1916:105-111. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8994-2_10. PMID: 30535688.

Figures