2795

Measures of vascular function influence the number and volume of white matter hyperintensities in older, hypertensive subjects1National Institute for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology, Chiba, Japan, 2CUBRIC, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 3CUBRIC, School of Physica and Astronomy, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 4CUBRIC, School of Psychology, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 5Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Aging

Damage to the deep white matter of the brain has been shown to correlate with hypertension and advanced age. However, the changes in the cerebral microvasculature that cause white matter lesions are unclear. Increased blood pressure causes morphological changes in cerebral vessels, and impaired vascular function and neurovascular coupling is a potential factor. Here, we demonstrate that age, central pulse pressure, and dual-echo MRI measures of CBF, CVR, CMRO2 and OEF influence the number and volume of white matter hyperintensities.Introduction

White matter hyperintensities (WMHs) are a common finding in brain imaging of older patients, particularly those with hypertension1, which correlate with cognitive impairment, and show up on T2-weighted FLAIR images as regions of hyperintense signal2. Small vessel disease is associated with WMHs and cognitive impairment, and impairment to neurovascular coupling may provide a link between systemic effects of hypertension and the development of WMHs3. Increased stiffness of cerebral vessels, a consequence of small vessel disease, can impair cerebrovascular reactivity and oxygen extraction4, which can be measured using fMRI with a gas challenge. Central pulse pressure has been shown to strongly relate to small vessel disease, WMHs, cognitive impairment, and stroke5. Measurement of CPP and cerebrovascular changes may be beneficial in determining the risk of WMHs, and understanding how they develop.Methods

Data was collected on 42 participants, with an age range of 55-84, and a BMI range 19-33. Three participants did not complete the scans, one participant was excluded due to inconsistencies in CPP measurement. Three participants were excluded due to failures of the the WM segmentation algorithm. Of the remaining participants, 17 (12 female, 5 male) completed the gas challenge, and this group were used for the final analysis. CPP was derived from carotid-femoral arterial stiffness measurements (Pulse Wave Analysis) in the supine position using the SphygmoCor (AtCor Medical, Australia) system. Participants underwent MRI scanning at 3T (Siemens 3T Prisma). A T2 weighted FLAIR scan, a T1 weighted MPRAGE scan, a dual-calibrated functional MRI (dcfMRI) scan6 and an inversion recovery scan were performed. The dcfMRI scan was accompanied by a 9-minute CO2 challenge, consisting of three blocks of 2 minutes CO2 and 1 minute medical air. The dcfMRI images were processed in Matlab to calculate global CBF, CMRO2, CVR and OEF. FLAIR and MPRAGE images were processed using a pre-trained deep learning algorithm7 to create masks of WMHs. Linear regression was performed in Matlab to identify correlations between Age, CPP, CBF, CMRO2, CVR, OEF, number of WMH clusters, and total WMH volume.Results

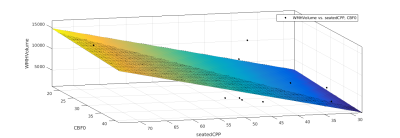

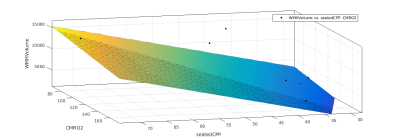

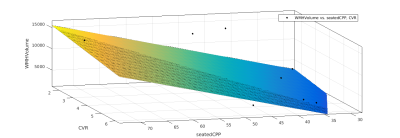

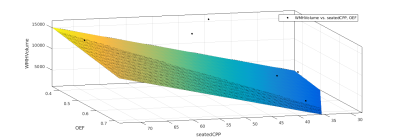

Age showed a small but significant correlation with number of WMH clusters (R2 = 0.252, P = 0.04). CPP showed a slightly larger correlation (R2 = 0.359, P = 0.011). DcfMRI measures did not show a significant correlation with number of WMH clusters. Multiple linear regression showed a higher correlation between Age+OEF and WMH clusters (R2 = 0.401, P = 0.0274), but combining age with other dcfMRI measures showed no correlation. Combining CPP with CVR and OEF each showed a small but significant increase in correlation with WMH cluster number (R2= 0.374, P = 0.0378 and R2 = 0.362, P = 0.043 respectively), while combining CPP with CBF or CMRO2 gave no change in correlation R2 = 0.359, P<0.05). CPP and age together showed the strongest correlation with WMH cluster number of any pair of factors (R2 = 0.601, P = 0.0016). Adding in dcfMRI measures caused a small but significant increase in correlation (CBF R2 = 0.607, P = 0.0057, CMRO2 R2 = 0.626, P = 0.0042, CVR R2 = 0.605, P = 0.00588, OEF R2 = 0.683, P = 0.00148). Age showed no correlation with total WMH volume. CPP showed a stronger correlation with WMH volume than cluster number (R2 = 0.388, P = 0.00756). Combining age with dcfMRI measures did not show any significant correlation with WMH volume. Combining CPP with dcfMRI measures showed an increased correlation for all four measures (CBF R2 = 0.393, P = 0.0302, CMRO2 R2 = 0.415, P = 0.0234, CVR R2 = 0.436, P = 0.0182, OEF R2 = 0.423, P = 0.0213). Combining CPP and age also showed an increased correlation (R2 = 0.549, P<0.01). Adding dcfMRI measures to age and CPP increased this correlation by a small but significant amount (CBF R2 =0..572, P = 0.00974, CMRO2 R2 = 0.55, P = 0.0132, CVR R2 = 0.555, P = 0.0123, OEF R2 = 0.553, P = 0.0129).Discussion

This analysis shows that vascular reactivity and oxygen extraction in small vessels increases the risk of WMHs with age and hypertension. WMHs had originally been thought to be a normal process of ageing, until a link was observed with cognitive impairment1. This data suggests that the development of WMHs is tied to age, however their severity is related to cardiovascular health. This suggests that small, benign lesions can be present in otherwise healthy older people, however those with a high CPP risk developing large lesions3, which are more likely to be related to cognitive impairment. Reduced oxygen extraction fraction combined with the effect of age also showed a strong correlation to the number of WMHs, supporting the link between oxidative stress and the development of WMHs. The effects of CBF, CVR and CMRO2 on WMHs is independent of age, but in subjects with high CPP shows an increased correlation with both WMH lesion number and total WMH volume. Taken together, this data suggests that the initial development of WMHs is a consequence of normal ageing and reduced oxygen metabolism, but their severity is determined by cardiovascular health and the effects on cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular activity.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Wellcome [WT200804;WT224267].References

1) Wardaw JM, Valdés Hernández MC, Muñoz-Maniega S, What are white matter hyperintensities made of? J Am Heart Assoc 2015; 4: e001140

2) Shrestha I, Takahashi T, Nomura E, Ohtsuki T, Ohshita T, Ueno H, Kohriyama T, Matsumoto M. Association between central systolic blood pressure, white matter lesions in cerebral MRI and carotid atherosclerosis. Hypertens Res 2009; 32: 869-874

3) Prins ND, Sheltens P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: an update. Nat Rev Neurol 2015; 11: 157-165.

4) Cannistraro RJ, Badi M, Eidelman BH, Dickson DW, Middlebrooks EH, Meschia JF. CNS small vessel disease: A clinical review. Neurol 2019; 92: 1146-1156

5) Schriffin EL. Vascular remodeling in hypertension. Hypertension 2012; 59: 367-374

6) Germuska M, Merola A, Muphy K, Babic A, Richmond L, Khot S, Hall JE, Wise RG. A forward modelling approach for the estimation of oxygen extraction fraction by calibrated fMRI. Neuroimage 2016; 139: 313-323

7) Li H, Jiang G, Zhang J, Wang R, Wang Z, Zheng W, Menze B. Fully convolutional network ensembles for white matter hyperintensities segmentation in MR images. Neuroimage 2018; 183: 650-665.