2793

Improving T2 distribution estimation using deep generative priors1UBC MRI Research Centre, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2Physics and Astronomy, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 3Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health, Vancouver, BC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Relaxometry, Brain, Myelin Water Fraction

$$$T_2$$$ distributions are typically computed using point estimates such as nonnegative least-squares (NNLS). This characterizes the most likely $$$T_2$$$-distribution arising from the data, but disregards other plausible solutions - of which there are many, due to the ill-posed nature of the inverse problem. Here, we instead propose to use Bayesian posterior sampling methods. To guide the difficult high-dimensional sampling problem, a data-driven domain transformation is learned alongside a deep generative prior. The resulting posterior samples produce more spatially consistent myelin water fraction (MWF) maps compared to NNLS, despite the purely voxelwise analysis, and additionally yields novel MWF uncertainty estimates.Introduction

The $$$T_2$$$-distribution of a multi spin-echo (MSE) magnitude signal is the set of coefficients resulting from a multiexponential signal decomposition. Basis signals are computed using the extended phase graph (EPG) algorithm, incorporating stimulated-echo and $$$B_1$$$-inhomogeneity effects1,2.$$$T_2$$$ distributions give insight into tissue microstructure. The myelin water fraction (MWF) of a white matter voxel characterizes myelin content, computed as the relative amount of signal contained in the fast decaying $$$T_2$$$ components3,4. In luminal water imaging of the prostate, reductions in slowly decaying $$$T_2$$$ components can inform prostate cancer diagnosis5,6.

$$$T_2$$$ distributions are commonly computed using point estimates such as nonnegative least-squares (NNLS). However, this ignores the large family of $$$T_2$$$ distributions which fit the data nearly equally well due to the ill-posed nature of the problem. Here we use Bayesian posterior sampling methods to quantify the full posterior space of $$$T_2$$$ distributions. Posterior sampling is difficult in high dimensions; to enable efficient sampling, we learn three deep networks: a data-dependent preconditioning transformation of the sampling space, a data-independent deep generative prior to guide sampling, and an encoder to embed the input data into a lower-dimensional representation. Once trained, posterior sampling using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) is performed in the usual way. This both improves $$$T_2$$$-distribution estimation, and allows us to compute novel uncertainty estimates of the derived MWF.

Methods

Let $$$\mathbf{b}\in\mathbb{R}_+^{n_{\mathrm{TE}}}$$$ be a measured MSE signal, $$$\mathbf{A}\in\mathbb{R}_+^{n_{\mathrm{TE}}\times{}n_{T_2}}$$$ be a matrix of EPG basis signals, and $$$\mathbf{x}\in\mathbb{R}_+^{n_{T_2}}$$$ be a $$$T_2$$$-distribution. The NNLS-based maximum a posteriori probability estimate $$$\mathbf{x}^{*}_{\mu}$$$ is $$\mathbf{x}^{*}_{\mu}=\underset{\mathbf{x}\ge{}0}{\operatorname{arg\,min}}\;||\mathbf{A}\mathbf{x}-\mathbf{b}||_2^2+\mu^2||\mathbf{x}||_2^2.$$ Implicitly, this imposes a uniform Gaussian noise model on $$$\mathbf{b}$$$, with $$$\ell^2$$$-regularization equivalent to a uniform half-normal prior on $$$\mathbf{x}$$$ with scale $$$1/\mu$$$. DECAES7 is used to compute $$$\mathbf{x}^{*}_{\mu}$$$, with $$$\mu$$$ determined using the L-curve method8,9.Here, we use posterior sampling to capture the diversity of plausible $$$T_2$$$ distributions. Posterior samples $$$\mathbf{x}$$$ are drawn using MCMC with frequency proportional to their posterior probability $$\mathbf{x}\sim{}p(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})\propto{}p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{x})p(\mathbf{x})$$ where $$$\mathbf{y}=(\mathbf{A},\mathbf{b})$$$ is the data, $$$p(\mathbf{x})$$$ is the prior distribution over $$$\mathbf{x}$$$, and $$$p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{x})$$$ is the likelihood of $$$\mathbf{b}\sim{}\operatorname{Rice}(\mathbf{v}=\mathbf{A}\mathbf{x},\sigma\operatorname{\mathbf{I}})$$$ under Rician noise10,11 $$\log{}p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{x})=\sum_{i=1}^{n_{\mathrm{TE}}}\log\tfrac{\mathbf{b}_{i}}{\sigma^2}+\log\operatorname{I}_0(\tfrac{\mathbf{b}_{i}\mathbf{v}_{i}}{\sigma^2})-\tfrac{\mathbf{b}_{i}^2+\mathbf{v}_{i}^2}{2\sigma^2}.$$ $$$\operatorname{I}_0$$$ is the modified Bessel function of the first kind with order zero. The full posterior includes the noise level $$$\sigma$$$, omitted throughout for brevity: $$$p(\mathbf{x},\sigma|\mathbf{y})\propto{}p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{x},\sigma)p(\mathbf{x})p(\sigma)$$$ with $$$p(\sigma)$$$ log-normal corresponding to $$$\text{SNR}=50\pm{}25$$$. Given posterior samples $$$\{\mathbf{x}_{i}\sim{}p(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})\}$$$, statistics of derived metrics $$$\{f(\mathbf{x}_{i})\}$$$ such as MWF are computed as expectations $$$\mathbb{E}_{p(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})} [f(\mathbf{x})] \approx \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i} f(\mathbf{x}_{i})$$$, and similarly for variances, quantiles, etc.

The high-dimensional ($$$n_{T_2}=40$$$) sampling problem is preconditioned through a judicious transformation of the sampling space. Let $$$\mathbf{x}=\varphi(\mathbf{u};\mathbf{y})$$$ be a data-dependent function of an unconstrained vector $$$\mathbf{u}$$$ defining a conditional normalizing flow12,13 from a base distribution $$$\pi(\mathbf{u})=\mathcal{N}(\operatorname{\mathbf{0}},\operatorname{\mathbf{I}})$$$ onto an approximate posterior $$$q_{\varphi}(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})$$$14: $$\log{}q_{\varphi}(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})=\log\pi(\mathbf{u})-\sum_{i=1}^{L}\log|\operatorname{det}{\mathbf{J}_{\varphi_{i}}}|$$ where $$$\varphi=\varphi_{L}\circ\cdots\circ\varphi_{1}$$$ is a composition of $$$L$$$ diffeomorphisms $$$\{\varphi_{i}\}_{i=1}^{L}$$$, $$$\mathbf{u}_{i}=\varphi_{i}(\mathbf{u}_{i-1};\mathbf{y})$$$ is the $$$i^{th}$$$ layer output, $$$\mathbf{J}_{\varphi_{i}}=\frac{\partial\mathbf{u}_{i}}{\partial\mathbf{u}_{i-1}}$$$ is the $$$i^{th}$$$ layer Jacobian, and $$$\varphi_{i}$$$ have closed-form Jacobian determinants $$$|\operatorname{det}{\mathbf{J}_{\varphi}}|=\prod_{i=1}^{L}|\operatorname{det}{\mathbf{J}_{\varphi_{i}}}|$$$. Preconditioning via $$$\varphi$$$ transforms the posterior sampling problem into $$\mathbf{u}\sim{}p(\mathbf{u}|\mathbf{y})=p(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})|\operatorname{det}{\mathbf{J}_{\varphi}}|\propto{}p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{x})p(\mathbf{x})|\operatorname{det}{\mathbf{J}_{\varphi}}|.$$ If $$$\varphi$$$ is well trained, $$$q_{\varphi}(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})\approx{}p(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})$$$ implies that $$$p(\mathbf{u}|\mathbf{y})\approx\pi(\mathbf{u})=\mathcal{N}(\operatorname{\mathbf{0}},\operatorname{\mathbf{I}})$$$ is easy to sample. The prior $$$p(\mathbf{x})$$$ is taken to be a deep generative prior $$$q_{\psi}(\mathbf{x})=\pi(\mathbf{u})/|\operatorname{det}{\mathbf{J}_{\psi}}|$$$. Similar to $$$\varphi(\mathbf{u};\mathbf{y})$$$, the diffeomorphism $$$\psi(\mathbf{u})$$$ defines an unconditional normalizing flow. Note that flows are generative: sampling occurs via $$$\mathbf{x}\sim{}q_{\varphi}(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})\Leftrightarrow\mathbf{u}\sim\mathcal{N}(\operatorname{\mathbf{0}},\operatorname{\mathbf{I}}),\,\mathbf{x}=\varphi(\mathbf{u};\mathbf{y})$$$.

An encoder network $$$\mathcal{E}:\mathbb{R}_+^{n_{\mathrm{TE}}}\times\mathbb{R}_+^{n_{\mathrm{TE}}\times{}n_{T_2}}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}^{n_{\mathbf{z}}}$$$ is used to reduce $$$\mathbf{y}$$$ to $$$(n_{\mathbf{z}}=12)$$$-dimensional embeddings $$$\mathbf{z}=\mathcal{E}(\mathbf{y})$$$, i.e. $$$q_{\varphi}(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{y})=q_{\varphi}(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{z}=\mathcal{E}(\mathbf{y}))$$$. The three networks $$$\varphi(\mathbf{u};\mathbf{z}),\,\psi(\mathbf{u}),\,\mathcal{E}(\mathbf{y})$$$ are trained jointly using amortized variational inference13,15-17 to minimize the following (negative) evidence lower bound (ELBO): $$\mathcal{L}_{\text{ELBO}}(\mathbf{y})=\underset{\mathbf{x}\sim{}q_{\varphi}(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{z})}{\mathbb{E}}[-\log{}p(\mathbf{y}|\mathbf{x})-\log{}q_{\psi}(\mathbf{x})+\log{}q_{\varphi}(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{z})]\quad\text{where}\quad\mathbf{z}=\mathcal{E}(\mathbf{y}).$$ Figure 1 illustrates how $$$\mathcal{L}_{\text{ELBO}}$$$ is computed.

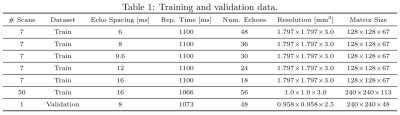

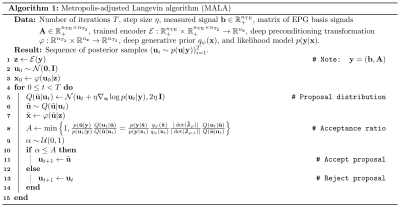

$$$\mathcal{E}$$$ consists of a 2-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP) (hidden dimension $$$512$$$, ReLU activation), a 2-layer transformer with multiheaded self-attention ($$$16$$$ heads, token size $$$128$$$), and another 2-layer MLP with output dimension $$$n_{\mathbf{z}}=12$$$; $$$\varphi(\mathbf{u};\mathbf{z})$$$ (similarly, $$$\psi(\mathbf{u})$$$) consists of $$$L=16$$$ (un)conditional linear coupling flows18,19 interleaved with orthogonal linear flows. The Adam20 optimizer is used with weight decay $$$\gamma=0.01$$$; initial learning rate $$$\eta=2\cdot{}10^{-4}$$$ decays to $$$\eta=10^{-7}$$$ following a cosine schedule; $$$500,\!000$$$ training steps are performed with mini-batches of $$$128\times{}(\mathbf{b},\mathbf{A})$$$ pairs; all $$$\mathbf{b},\mathbf{A}$$$ are padded with zeros to length $$$n_{\mathrm{TE}}=56$$$; data is augmented by random masking to length $$$16\le{}n_{\mathrm{TE}}\le{}56$$$; training/validation datasets are detailed in Table 1. After training, sampling $$$\mathbf{u}\sim{}p(\mathbf{u}|\mathbf{y})$$$ is performed via the Metropolis-adjusted Langevin algorithm (MALA); see Algorithm 1.

Results

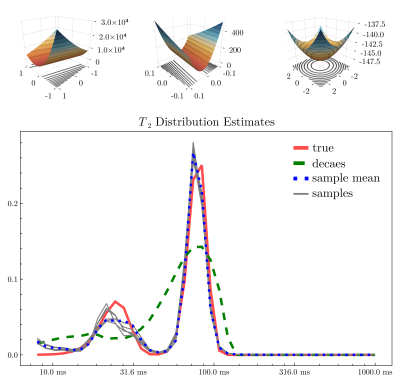

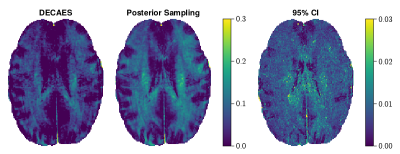

Figure 4 illustrates the posterior likelihood surface $$$-\!\log{}p(\mathbf{u}|\mathbf{y})$$$ in two random orthogonal directions before and after applying the learned preconditioning $$$\varphi$$$. The surface becomes more symmetric and well-conditioned, making exploration of the posterior space feasible. In lieu of a gold-standard method for comparison, in Figure 4 we compare NNLS with posterior sampling on a toy bimodal $$$T_2$$$-distribution corrupted with Rician noise ($$$\text{SNR}=50$$$). Posterior sampling both captures the peaks more faithfully, and illustrates the variety of plausible short peaks. Figure 5 compares MWF images on a validation image. MWF computed via MALA appears more spatially uniform, despite independent voxelwise sampling.Discussion and conclusion

We have shown that posterior sampling over a learned manifold of $$$T_2$$$ distributions, aided by a deep generative prior, is feasible and indeed beneficial when compared with NNLS-based methods. Note that this does come at a cost: $$$T_2$$$ distributions significantly different than those seen during training will be avoided by the deep prior. We have not observed this issue, likely due to the size and diversity of the training set.Acknowledgements

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Grant/Award Number 016-05371, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Grant Number RN382474-418628, the National MS Society (RG-1507-05301). J.D. is supported by NSERC Doctoral Award and Izaak Walton Killam Memorial Pre-Doctoral Fellowship. A.R. is supported by Canada Research Chairs 950-230363. This work was conducted on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories of Coast Salish Peoples, including the territories of the xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.References

[1] J Hennig. Multiecho imaging sequences with low refocusing flip angles. Journal of Magnetic Resonance (1969), 78(3):397–407, July 1988.

[2] Thomas Prasloski, Burkhard M ̈adler, Qing-San Xiang, Alex MacKay, and Craig Jones. Applications of stimulated echo correction to multicomponent T2 analysis. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 67(6):1803–1814, 2012. eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/mrm.23157.

[3] Alex Mackay, Kenneth Whittall, Julian Adler, David Li, Donald Paty, and Douglas Graeb. In vivo visualization of myelin water in brain by magnetic resonance. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 31(6):673–677, 1994.

[4] Kenneth P Whittall and Alexander L MacKay. Quantitative interpretation of NMR relaxation data. Journal of Magnetic Resonance (1969), 84(1):134–152, August 1989.

[5] Shirin Sabouri, Silvia D. Chang, Richard Savdie, Jing Zhang, Edward C. Jones, S. Larry Goldenberg, Peter C. Black, and Piotr Kozlowski. Luminal Water Imaging: A New MR Imaging T2 Mapping Technique for Prostate Cancer Diagnosis. Radiology, 284(2):451–459, April 2017. Publisher: Radiological Society of North America.

[6] Shirin Sabouri, Ladan Fazli, Silvia D. Chang, Richard Savdie, Edward C. Jones, S. Larry Goldenberg, Peter C. Black, and Piotr Kozlowski. MR measurement of luminal water in prostate gland: Quantitative correlation between MRI and histology. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging: JMRI, 46(3):861–869, 2017.

[7] Jonathan Doucette, Christian Kames, and Alexander Rauscher. DECAES – DEcomposition and Component Analysis of Exponential Signals. Zeitschrift f ̈ur Medizinische Physik, 30(4):271–278, November 2020.

[8] Per Christian Hansen. Analysis of Discrete Ill-Posed Problems by Means of the L-Curve. SIAM Review, 34(4):561–580, December 1992. Publisher: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

[9] Alessandro Cultrera and Luca Callegaro. A simple algorithm to find the L-curve corner in the regularisation of ill-posed inverse problems. IOP SciNotes, 1(2):025004, August 2020. Publisher: IOP Publishing.

[10] S. O. Rice. Mathematical Analysis of Random Noise. Bell System Technical Journal, 23(3):282–332, 1944. eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1944.tb00874.x.

[11] S. O. Rice. Mathematical Analysis of Random Noise. Bell System Technical Journal, 24(1):46–156, 1945. eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1945.tb00453.x.

[12] Ivan Kobyzev, Simon J.D. Prince, and Marcus A. Brubaker. Normalizing Flows: An Introduction and Review of Current Methods. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 43(11):3964–3979, November 2021. Conference Name: IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence.

[13] George Papamakarios, Eric Nalisnick, Danilo Jimenez Rezende, Shakir Mohamed, and Balaji Lakshminarayanan. Normalizing Flows for Probabilistic Modeling and Inference. arXiv:1912.02762 [cs, stat], April 2021. arXiv: 1912.02762.

[14] Matthew Hoffman, Pavel Sountsov, Joshua V. Dillon, Ian Langmore, Dustin Tran, and Srinivas Vasudevan. NeuTra-lizing Bad Geometry in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo Using Neural Transport, March 2019. arXiv:1903.03704 [stat].

[15] Diederik P. Kingma and Max Welling. Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes. arXiv:1312.6114 [cs, stat], May 2014. arXiv: 1312.6114.

[16] Danilo Jimenez Rezende, Shakir Mohamed, and Daan Wierstra. Stochastic Backpropagation and Approximate Inference in Deep Generative Models. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 1278–1286. PMLR, June 2014. ISSN: 1938-7228.

[17] Danilo Jimenez Rezende and Shakir Mohamed. Variational Inference with Normalizing Flows. arXiv:1505.05770 [cs, stat], June 2016. arXiv: 1505.05770.

[18] Laurent Dinh, David Krueger, and Yoshua Bengio. NICE: Non-linear Independent Components Estimation, April 2015. arXiv:1410.8516 [cs].

[19] Laurent Dinh, Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, and Samy Bengio. Density estimation using Real NVP, February 2017. arXiv:1605.08803 [cs, stat].

[20] Diederik P. Kingma and Jimmy Ba. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv:1412.6980 [cs], December 2014. arXiv: 1412.6980.

[21] D. Bakry and M. ́Emery. Diffusions hypercontractives. In Jacques Az ́ema and Marc Yor, editors, S ́eminaire de Probabilit ́es XIX 1983/84, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, pages 177–206, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1985. Springer.

[22] Gareth O. Roberts and Jeffrey S. Rosenthal. Optimal scaling of discrete approximations to Langevin diffusions. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology), 60(1):255–268, 1998. eprint: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/1467-9868.00123.4

Figures