2791

Deep learning-based quantification of white matter hyperintensity applicable to real-world clinical FLAIR images1The Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States, 2F. M. Kirby Research Center for Functional Brain Imaging, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3The Richman Family Precision Medicine Center of Excellence in Alzheimer’s Disease, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Neurodegeneration, White Matter Hyperintensity

White matter hyperintensity (WMH) in the brain is known to correlate with cognitive prognosis in many diseases; automated quantification tools for WMH have been developed, but most have been used to quantify study data from specific diseases imaged with a single scanning protocol. The low accuracy of these tools when used for clinical data with diverse scan protocols and diseases has been a problem in clinical applications. To overcome this limitation, we developed a deep-learning-based WMH quantification model for real-world clinical FLAIR images with high heterogeneity. The results show the potential of this method as a clinical tool.Introduction

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) in T2-weighted Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) images are one of the most common features related to cognitive impairments (1). They are mainly caused by microvascular degeneration and are closely associated with major brain disorders, including stroke and dementia (2). Due to the labor-intensive task of manual segmentation, automated WMH quantification tools have been widely developed, including various forms of intensity-based thresholding methods (3-8), clustering and machine-learning methods (9-12), outlier analysis methods (8, 13-15), morphological operations (16, 17), Bayesian approaches (12, 18), and, very recently, deep-learning (DL) methods (19-22). Among these existing WMH labeling methods, the DL-based techniques are the most promising approach since they have successfully identified salient features of various types of images, with an accuracy that often outperforms professional judgment (23-30). However, most DL methods are trained only through highly homogeneous research data, such as well-organized scanning protocols and focus on relatively mild-to-moderate cases. In actual clinical practice, patients often have several non-WMH lesions with different neuro-anatomical features and are scanned with different protocols on scanners from different vendors, field strengths, and voxel resolutions. These biological and technical heterogeneities make it difficult for existing DL models to detect WMH accurately. Furthermore, T1-weighted and 3D-FLAIR images are necessary for segmentation in most tools (31-34), which poses another challenge for clinical implementation by limiting applicability. To overcome these limitations, we focused on using real-world clinical FLAIR images to train the model. Comparison with manual segmentation revealed that our model can segment WMH using 2D-FLAIR images alone, regardless of severity, the presence of non-WMH lesion areas, or variations in scanning parameters.Methods

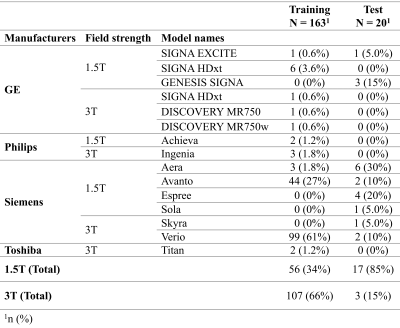

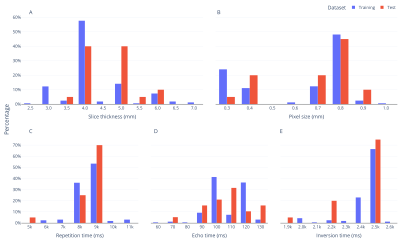

1. Training dataFLAIR images of 163 patients were obtained from the Richman Family Precision Medicine Center of Excellence (PMCoE) in Alzheimer's Disease (AD) database that consists of clinical MRIs scanned for clinical indications. The PMCoE database contains MRIs with various scanners (GE, Philips, Siemens, and Toshiba), scan parameters (magnetic field strength: 1.5T and 3T, slice thickness: 2-7mm, in plane resolutions: 0.3-1.0mm, repetition time: 5000-11000ms, echo time: 60-130ms, inversion time: 19000-26000ms, 2D and 3D scans), and clinical conditions (AD, vascular dementia, and mixed dementias). The distributions of these scan parameters are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. For each FLAIR image, WMH was manually classified into periventricular WMH (pWMH) and deep WMH (dWMH).

2. Fully-automated WMH segmentation model

The ResNet, developed for the deep residual learning of image recognition, was used as the model for the WMH parcellation. Our ResNet model consists of five stages, each with a convolution and identity block. Each convolution block has three convolution layers, and each identity block also has three convolution layers. The model is trained to receive WMH labels as input and the trained model produces the WMH labels on the FLAIR images.

3. Test data

As for the model validation, a total of 20 new patients were randomly selected from the PMCoE data, five for each severity (mild, moderate, severe, with some non-WMH lesions) defined by the Fazekas score (36). Manual segmentation by one of authors (KOn) was used as a reference for the following statistical analysis.

4. Statistical analysis

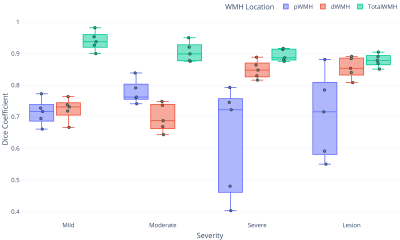

Two types of statistics were applied to evaluate the model’s performance. To evaluate consistency, Pearson’s correlation test was performed between WMH volumes measured by automated and manual (gold-standard) methods. To evaluate the accuracy, Dice coefficients were calculated between the WMH labels obtained from the automated and manual methods. The Dice coefficients were calculated separately for pWMH, dWMH, and total WMH (sum of pWMH and dWMH).

Results and discussion

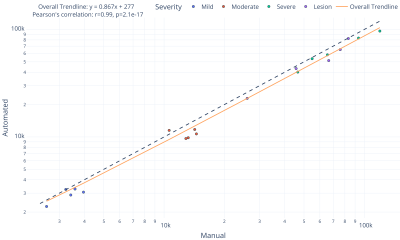

1. Correlation between automated and manual WMH quantificationFigure 2 shows the scatter plot representing the relationship between total WMH volumes measured by the automated and manual methods. An excellent correlation (r=0.99, p=2.1×10-17) was found between them, indicating that our automated method is comparable to manual segmentation regardless of the severity or the existence of non-WMH lesions. The slope value of the overall trend line was 0.87, suggesting a slight underestimation tendency of the automated method.

2. Dice coefficient

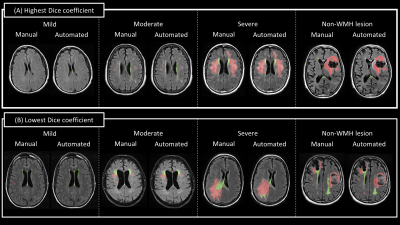

Representative images of WMH segmentation are shown in Figure 3. For each severity, results with the highest and lowest Dice coefficient are presented. The Dice coefficients of total WMH were above 0.85 (average of 0.90 for all cases), confirming the highly accurate WMH detection performance (Fig. 4). Interestingly, greater variation was found in the Dice coefficients of pWMH of the severe lesion groups, indicating that the discrimination between pWMH and dWMH becomes more difficult as the WMH lesion area increases (Figure 2 (B)).

Conclusion

The ResNet-based WMH segmentation model performed comparably to manual segmentation, even on real clinical data with high biological and technical heterogeneity. Further research, including more training and test data on various types of brain diseases, is needed to validate the model as a clinically applicable tool.Acknowledgements

This work is supported by funding from National Institutes of Health (R21AG070404) and the Richman Family Precision Medicine Center of Excellence in Alzheimer's Disease, including significant contributions from the Richman Family Foundation, the Rick Sharp Alzheimer’s Foundation, the Sharp Family Foundation, and others. SM is a founder and KOi is a consultant for “AnatomyWorks” and “Corporate-M.” This arrangement is being managed by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policies.References

1. Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3666.

2. Wardlaw JM, Hernández MCV, Muñoz‐Maniega S. What are White Matter Hyperintensities Made of? Journal of the American Heart Association. 2015;4(6):e001140.

3. Simoes R, Monninghoff C, Dlugaj M, Weimar C, Wanke I, van Walsum AMV, et al. Automatic segmentation of cerebral white matter hyperintensities using only 3D FLAIR images. Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;31(7):1182-9.

4. Ji SX, Ye CQ, Li F, Sun W, Zhang J, Huang YN, et al. Automatic segmentation of white matter hyperintensities by an extended FitzHugh & nagumo reaction diffusion model. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2013;37(2):343-50.

5. Yoo BI, Lee JJ, Han JW, Oh SYW, Lee EY, MacFall JR, et al. Application of variable threshold intensity to segmentation for white matter hyperintensities in fluid attenuated inversion recovery magnetic resonance images. Neuroradiology. 2014;56(4):265-81.

6. Jack CR, O'Brien PC, Rettman DW, Shiung MM, Xu YC, Muthupillai R, et al. FLAIR histogram segmentation for measurement of leukoaraiosis volume. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2001;14(6):668-76.

7. Admiraal-Behloul F, van den Heuvel DMJ, Olofsen H, van Osch MJP, van der Grond J, van Buchem MA, et al. Fully automatic segmentation of white matter hyperintensities in MR images of the elderly. Neuroimage. 2005;28(3):607-17.

8. Ong KH, Ramachandram D, Mandava R, Shuaib IL. Automatic white matter lesion segmentation using an adaptive outlier detection method. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;30(6):807-23.

9. Lao ZQ, Shen DG, Liu DF, Jawad AF, Melhern ER, Launer LJ, et al. Computer-assisted segmentation of white matter lesions in 3D MR images using support vector machine. Acad Radiol. 2008;15(3):300-13.

10. Dyrby TB, Rostrup E, Baare WFC, van Straaten ECW, Barkhof F, Vrenken H, et al. Segmentation of age-related white matter changes in a clinical multi-center study. Neuroimage. 2008;41(2):335-45.

11. Seghier ML, Ramlackhansingh A, Crinion J, Leff AP, Price CJ. Lesion identification using unified segmentation-normalisation models and fuzzy clustering. Neuroimage. 2008;41(4):1253-66.

12. Ithapu V, Singh V, Lindner C, Austin BP, Hinrichs C, Carlsson CM, et al. Extracting and Summarizing White Matter Hyperintensities Using Supervised Segmentation Methods in Alzheimer's Disease Risk and Aging Studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2014;35(8):4219-35.

13. Maldjian JA, Whitlow CT, Saha BN, Kota G, Vandergriff C, Davenport EM, et al. Automated White Matter Total Lesion Volume Segmentation in Diabetes. Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(12):2265-70.

14. Yang FG, Shan ZY, Kruggel F. White matter lesion segmentation based on feature joint occurrence probability and chi(2) random field theory from magnetic resonance (MR) images. Pattern Recogn Lett. 2010;31(9):781-90.

15. Van Leemput K, Maes F, Vandermeulen D, Colchester A, Suetens P. Automated segmentation of multiple sclerosis lesions by model outlier detection. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2001;20(8):677-88.

16. Shi L, Wang DF, Liu SP, Pu YH, Wang YL, Chu WCW, et al. Automated quantification of white matter lesion in magnetic resonance imaging of patients with acute infarction. J Neurosci Meth. 2013;213(1):138-46.

17. Beare R, Srikanth V, Chen J, Phan TG, Stapleton J, Lipshut R, et al. Development and validation of morphological segmentation of age-related cerebral white matter hyperintensities. Neuroimage. 2009;47(1):199-203.

18. Herskovits EH, Bryan RN, Yang F. Automated Bayesian Segmentation of Microvascular White-Matter Lesions in the ACCORD-MIND Study. Adv Med Sci-Poland. 2008;53(2):182-90.

19. Rachmadi MF, Valdes-Hernandez MDC, Agan MLF, Di Perri C, Komura T, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. Segmentation of white matter hyperintensities using convolutional neural networks with global spatial information in routine clinical brain MRI with none or mild vascular pathology. Computerized medical imaging and graphics : the official journal of the Computerized Medical Imaging Society. 2018;66:28-43.

20. Ding T, Cohen AD, O'Connor EE, Karim HT, Crainiceanu A, Muschelli J, et al. An improved algorithm of white matter hyperintensity detection in elderly adults. NeuroImage Clinical. 2020;25:102151.

21. Moeskops P, de Bresser J, Kuijf HJ, Mendrik AM, Biessels GJ, Pluim JPW, et al. Evaluation of a deep learning approach for the segmentation of brain tissues and white matter hyperintensities of presumed vascular origin in MRI. NeuroImage Clinical. 2018;17:251-62.

22. Rachmadi MF, Valdes-Hernandez MDC, Makin S, Wardlaw J, Komura T. Automatic spatial estimation of white matter hyperintensities evolution in brain MRI using disease evolution predictor deep neural networks. Medical image analysis. 2020;63:101712.

23. Sohaib M, Kim CH, Kim JM. A Hybrid Feature Model and Deep-Learning-Based Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Sensors (Basel). 2017;17(12).

24. Loh BCS, Then PHH. Deep learning for cardiac computer-aided diagnosis: benefits, issues & solutions. mHealth. 2017;3:45.

25. Thung KH, Yap PT, Shen D. Multi-stage Diagnosis of Alzheimer's Disease with Incomplete Multimodal Data via Multi-task Deep Learning. Deep learning in medical image analysis and multimodal learning for clinical decision support : third International Workshop, DLMIA 2017, and 7th International Workshop, ML-CDS 2017, h. 2017;10553:160-8.

26. Nishikawa RM, Bae KT. Importance of Better Human-Computer Interaction in the Era of Deep Learning: Mammography Computer-Aided Diagnosis as a Use Case. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2018;15(1 Pt A):49-52. 27. Weng S, Xu X, Li J, Wong STC. Combining deep learning and coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering imaging for automated differential diagnosis of lung cancer. Journal of biomedical optics. 2017;22(10):1-10.

28. Suk HI, Lee SW, Shen D. Deep sparse multi-task learning for feature selection in Alzheimer's disease diagnosis. Brain structure & function. 2016;221(5):2569-87.

29. Li R, Zhang W, Suk HI, Wang L, Li J, Shen D, et al. Deep learning based imaging data completion for improved brain disease diagnosis. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2014;17(Pt 3):305-12.

30. Suk HI, Lee SW, Shen D. Hierarchical feature representation and multimodal fusion with deep learning for AD/MCI diagnosis. Neuroimage. 2014;101:569-82.

31. Mojiri Forooshani P, Biparva M, Ntiri EE, Ramirez J, Boone L, Holmes MF, et al. Deep Bayesian networks for uncertainty estimation and adversarial resistance of white matter hyperintensity segmentation. Human Brain Mapping. 2022;43(7):2089-108.

32. Moeskops P, de Bresser J, Kuijf HJ, Mendrik AM, Biessels GJ, Pluim JPW, et al. Evaluation of a deep learning approach for the segmentation of brain tissues and white matter hyperintensities of presumed vascular origin in MRI. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2018;17:251-62.

33. Kuijf HJ, Biesbroek JM, Bresser JD, Heinen R, Andermatt S, Bento M, et al. Standardized Assessment of Automatic Segmentation of White Matter Hyperintensities and Results of the WMH Segmentation Challenge. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 2019;38(11):2556-68.

34. Doshi J, Erus G, Habes M, Davatzikos C. DeepMRSeg: A convolutional deep neural network for anatomy and abnormality segmentation on MR images. arXiv preprint arXiv:190702110. 2019.

35. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J, editors. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 27-30 June 2016.

36. Fazekas F, Chawluk JB, Alavi A, Hurtig HI, Zimmerman RA. MR signal abnormalities at 1.5 T in Alzheimer's dementia and normal aging. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1987;149(2):351-6.

Figures