2790

Brain WMH Load, Kinetics and regional Distribution with Aging: A signature of Structural and Cognitive Health

Niraj Kumar Gupta1, Neha Yadav1, Aniket Aman1, and Vivek Tiwari1

1Department of Biological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Berhampur, Berhampur, India

1Department of Biological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Berhampur, Berhampur, India

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Aging

Discriminating Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease is challenging due to overlapping subtle structural changes and cognitive variations. Load and distribution of white matter hyperintensity across brain regions may elicit structural atrophy and cognitive disabilities via continuous vascular insult. Here, we have investigated the kinetics and regional distribution of White matter hyperintensity with aging and its implications in brain structure and cognitive health using T2-FLAIR and T1w longitudinal MRI from the NACC cohort.Introduction

Cerebral Small Vessel Disease (CSVD) is among the most common pathologies of the aging brain, which occurs due to infarcts in small perforating arteries and arterioles1. Chronic ischemia associated with CSVD is seen as White Matter Hyperintensity (WMH) on the T2-FLAIR MR images. White matter hyperintensity (WMH) accumulation across periventricular (PVWMH) and deep white matter (DWMH) is often seen in the aging brain. However, we do not yet understand the impact of cerebrovascular pathologies on the aging trajectory and its potential contribution towards cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Here, we have investigated the load of WMH across the periventricular, deep white matter, brain lobes, and regions associated with specific arterial segments in cognitively normal (CN), cognitively impaired (CI), and subjects with an etiological diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease (CI-AD) using the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) cohort to understand the effect of WMH load and kinetics on brain structure and cognition.Methods

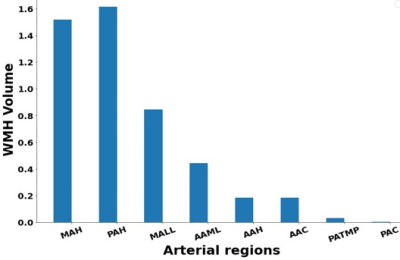

T2-FLAIR and T1-weighted (T1w) MRI from subjects with normal cognition (CN, N=734), cognitive impairment because of MCI (CI-MCI, N=110), Cognitive impairment because of other etiologies than MCI (CI-others, N=58) and cognitive impairment with AD (CI-AD, N=337) from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) was segmented for quantification of WMH. A cluster-based white matter hyperintensity (WMH) extraction pipeline based on k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) algorithm, UBO Detector2 was employed for segmentation and measurement of periventricular white matter hyperintensity (PVWMH), deep white matter hyperintensity (DWMH), regional WMH load (frontal, parietal, temporal and occipital). The segmentation methods involved the optimization of kNN and probability threshold. The brain MRI images were further segmented for WMH quantitation across 8 arterial regions corresponding to arterial branching across various white matter regions. The arterial white matter regions included are the Middle artery hemisphere (MAH), Posterior artery hemisphere (PAH), Middle artery lateral lenticulostriate (MALL), Anterior artery medial lenticulostriate (AAML), Anterior artery hemisphere (AAH), Anterior artery callosal (AAC), Posterior artery thalamic and midbrain perforators (PATMP), Posterior artery callosal (PAC). The quantity of WMH load in various cognitive groups was stratified across three age groups: early (50-64 years), intermediate (65-79 years), and late age group (>79 years). Non-parametric test - Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction was performed to check for significant differences in multiple pairwise comparisons. WMH load segmented across PVWMH, DWMH, regional lobes, and arterial segmentation was investigated for its impact on cognition and neuroanatomic volumes with aging across CN, CI-MCI, CI-others, and CI-AD subjects.Results and Discussion

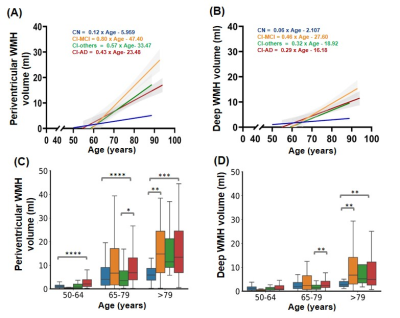

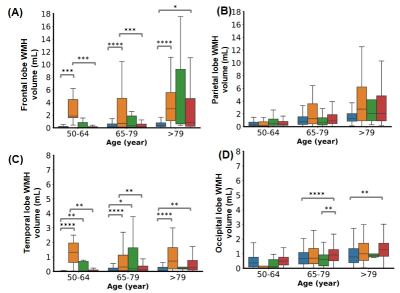

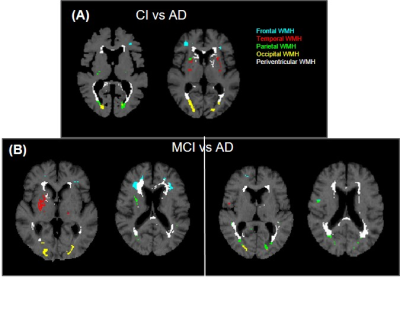

The total WMH load increased progressively with age across all the cognitive groups [Fig.1]. However, the rate of increase of WMH volume with age is significantly higher in cognitively impaired groups (CI-MCI, CI-others and CI-AD) compared to the Cognitively Normal (CN) subjects. The rate of increase in Periventricular WMH volume was significantly higher (~2x, p<0.01) across cognitive groups when compared to that of progression in DWMHs [Fig.2]. Noticeably, WMH load was distinct across the brain regions for CN, CI-MCI, CI-others, and CI-AD across the age groups wherein frontal and parietal lobes exhibited significantly higher (p<0.01) WMH load, compared to temporal and occipital brain regions [Fig.3]. Interestingly, CI-MCI subjects showed a significantly increased load of WMH in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and posterior artery callosal (PAC) region compared to the CI-AD subjects [Fig.3,4]. However, CI-AD had significantly increased PVWMH and DWMH compared to subjects with cognitive impairment due to other forms of dementia [Fig.3,4]. Moreover, segmentation of WMH across arterial branches revealed a pattern of WMH distribution marked with increased WMH load in the Middle Artery Hemisphere and Posterior Artery Hemisphere regions while minimal accumulation of WMH in PATMP and PAC branches [Fig.5]. A significant negative association between whole brain/periventricular WMH load and cognitive performance was observed to be associated with a decline in executive functions and global cognition(p<0.0001).Conclusion

The rate of progression of WMH is significantly faster in cognitively impaired subjects suggestive of increased vascular insults on neuroanatomic health owing to WMH accumulation. WMH load across brain regions have distinct regional and arterial patterns between MCI and AD subjects. The temporal and spatial accumulation of periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensity with aging are the potential vascular indicators of brain structural health and cognitive abilities.Acknowledgements

The data support from National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre (NACC) database funded by NIA/NIH Grant U24 AG072122References

1. Li Q, Yang Y, Reis C, et al., Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Cell Transplant. 2018 Dec;27(12):1711-1722. doi: 10.1177/0963689718795148. Epub 2018 Sep 25. PMID: 30251566; PMCID: PMC6300773

2. Jiang J, Liu T, et al., UBO Detector - A cluster-based, fully automated pipeline for extracting white matter hyperintensities. Neuroimage. 2018 Jul 1;174:539-549. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.03.050. Epub 2018 Mar 22. PMID: 29578029.

Figures

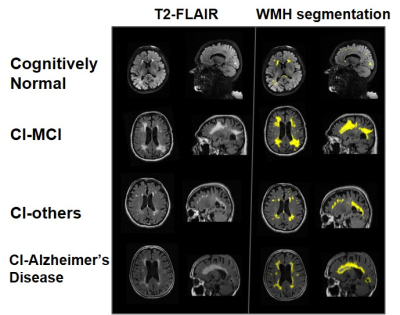

Fig.1- Axial and sagittal view of Brain MRI showing WMH load in T2 FLAIR (left) and segmentation result (right) in CN, CI-MCI, CI-others, and CI-AD subjects of the same age group (80 years)

Fig.2- Linear regression of (A) Periventricular and (B) Deep White Matter Hyperintensity load with age across different cognitive groups; Age-group wise distribution of (C) Periventricular and (D) Deep WMH across cognitive groups. Statistical significance for multiple comparisons using Mann Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001

Fig.3- WMH volume distribution in (A) frontal, (B) parietal, (C) temporal, (D) occipital lobes of the brain in three age groups. No significant difference was found in the parietal lobe across the cognitive groups. Statistical significance for multiple comparisons using Mann Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001

Fig.4- T1w MRI images showing WMH segmentation mask (A) CI vs AD: AD subjects possess higher periventricular and deep white matter hyperintensity than CI, (B) MCI vs AD: There is higher WMH load in MCI in frontal and temporal regions than AD

Fig.5- Median WMH volume distribution in the eight arterial white matter regions

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2790