2787

Machine-learning prediction of fMRI language laterality based on morphological features of Arcuate fasciculi CSD tractograms1Imaging and pathology, Translational MRI, KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, Tractography & Fiber Modelling

Shape features of the arcuate fasciculi (AF) can be used for predicting language laterality by a machine-learning algorithm as determined by language task-based functional MRI (tb-fMRI) laterality index (LI) relatively accurately (AUC = 0.893, accuracy = 0.868) in a sample of 60 clinical preoperative patients with variable pathology. Constrained spherical deconvolution (CSD) tractograms seemed to give the best outcome of model training regardless of additional streamline filtering or anatomical constraint. The best-performing model appeared to prioritise bundle curl, irregularity and span over the more conventional measures of surface-area and volume.Introduction

Hemispheric language dominance (laterality) is important in presurgical planning and is typically established using the laterality index (LI) from Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) task-based language fMRI 1. However, in some patients, tb-fMRI may fail to determine language laterality for example, due to difficulties related to task performance 2. While resting-state fMRI (rs-fMRI), which requires no task performance, could potentially be used as an alternative, the literature remains inconclusive about this possibility 3–6. Diffusion MRI (dMRI) tractography of the language bundles, e.g. the arcuate fasciculus (AF), could be used as an alternative to predict language laterality. Based on structural-functional coupling 7, one could expect the structure and morphology of the AF to hold enough information for language dominance prediction.Current literature on the topic is relatively sparse and provides no consensus 8–14. Most studies focused on volume, voxel count, and scalar metrics such as fractional anisotropy (FA), and mean diffusivity (MD). The majority of them also used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) 15–17 rather than more advanced dMRI models such as constrained spherical deconvolution (CSD) 18 fiber tracking, which can accurately reconstruct complex fiber architecture.

The machine learning algorithm XGBoost 19 has gained success as a powerful model to process tabular data. This work explores the feasibility of using morphological metrics derived from AF tractograms to train XGBoost models to predict language dominance as measured by fMRI LI in a cohort of clinical patients with diverse pathology.

Material and Methods

Seventy-nine clinical surgically-naive neurosurgical patients (median age=39, IQR=25.5) were recruited, all of whom received oral and written information and provided oral and written consent. Patients were excluded from this study for lack of language tb-fMRI (N = 19), table 1a lists patient demographics and pathology. The study was performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki with approval by the institutional ethical committee.MRI acquisition used two 3-Tesla scanners with 32-channel phased-array receive only head-coils. Imaging included sagittal 3D T1-, T2- and T2 fluid-attenuation inversion-recovery (FLAIR) weighted structural images, dMRI, and BOLD tb-fMRI images, detailed in table 1b. Language tb-fMRI used a symmetrical [1] [2] 30-seconds block design with the verb-to-noun generation task. Language functional maps were generated with SPM first-level analysis after motion correction and coregistration of BOLD data to native 3D-T1s 20. Language LI values were calculated between the left and right hemispheres for 60 subjects (53 left dominant, 7 right dominant).

Lesions were semi-automatically segmented using ITK-snap 21, followed by T1 lesion-inpainting 22 and structural parcellation 23,24. AF DTI and CSD probabilistic tractograms were generated with 6000 initial streamlines with and without streamlines filtering and anatomical constraints using KUL_FWT 25. Tractogram shape features (curl, length, diameter, elongation, volume, surface area, span, and irregularity) were calculated based on Yeh, 2020 26. To compensate for the scarcity of right dominant language patients (N = 7), we flipped the dataset in left-to-right and added it to the data pool. The entire dataset was split into separate training (70%) and testing sets (30%).

XGBoost performed a regression with the input features as predictors and the fMRI LI as the target. XGBoost models were trained and tested on different permutations of input features from tractograms generated with DTI and/or CSD, with and/or without streamline filtering, and/or anatomical-constraints, and flipped or not. An ROC analysis was then used to determine the ideal cutoff for classification based on regression output.

Results & Discussion

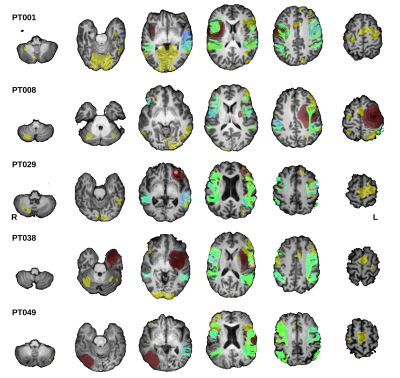

Tractography resulted in 120 bundles for each combination of tractography method (DTI or CSD), and filtering configuration. Figure 1 shows tractograms generated with CSD and both filtering approaches from 5 exemplar patients.A total of 1621 models were successfully trained and tested. The highest performance (testing AUC = 0.893, accuracy = 0.868) was achieved by training on data derived from iFOD2 tractograms, with and without filtering and anatomical-constraint, and including the flipped data, Figure 2.

While these results may indicate that CSD tractograms are more consistent with language fMRI results, and may thus be better for predicting language dominance. The difference between the best performing model trained on CSD (AUC = 0.893) and on DTI (AUC = 0.860) was minor. In addition, anatomical constraints seemed to benefit models trained on CSD tractograms but had the opposite effect on those trained on DTI tractograms.

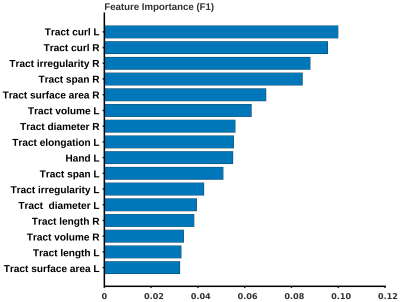

The most important features selected by the best performing model were the left and right bundle curl, right bundle irregularity, span, and surface area metrics from left and right bundles, Figure 3.

This work represents a proof of concept that white matter structure holds enough information to train a model to determine language laterality. White matter bundle structure could hold many insights yet to be discovered. This task-less approach could serve as an additional tool in the clinic to determine LI. Further development with larger datasets and more balanced representation of left and right-dominant language patients could result in better performing models. Performance could also be improved by including healthy subjects and additional features, such as streamline count, scalar values, or other bundles, e.g. inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus.

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Middlebrooks, E. H., Yagmurlu, K., Szaflarski, J. P., Rahman, M. & Bozkurt, B. A contemporary framework of language processing in the human brain in the context of preoperative and intraoperative language mapping. Neuroradiology 59, 69–87 (2017).

2. Seghier, M. L. Laterality index in functional MRI: methodological issues. Magn. Reson. Imaging 26, 594–601 (2008).

3. Manan, H. A., Franz, E. A. & Yahya, N. The utilisation of resting-state fMRI as a pre-operative mapping tool in patients with brain tumours in comparison to task-based fMRI and intraoperative mapping: A systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl.) 30, e13428 (2021).

4. Rolinski, R. et al. Language lateralization from task‐based and resting state functional MRI in patients with epilepsy. Hum. Brain Mapp. 41, 3133–3146 (2020).

5. Phillips, N. L., Shatil, A. S., Go, C., Robertson, A. & Widjaja, E. Resting-State Functional MRI for Determining Language Lateralization in Children with Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 42, 1299–1304 (2021).

6. Bhroin, M. N., Molloy, E. J. & Bokde, A. L. W. Relationship between resting-state fMRI functional connectivity with motor and language outcome after perinatal brain injury – A systematic review. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 33, 36–49 (2021).

7. Rodrigo, S. et al. Language lateralization in temporal lobe epilepsy using functional MRI and probabilistic tractography. Epilepsia 49, 1367–1376 (2008).

8. Allendorfer, J. B. et al. Arcuate fasciculus asymmetry has a hand in language function but not handedness. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 3297–3309 (2016).

9. Delgado-Fernández, J. et al. Language hemispheric dominance analyzed with magnetic resonance DTI: correlation with the Wada test. J. Neurosurg. 134, 1703–1710 (2020).

10. McDonald, C. R. et al. Diffusion tensor imaging correlates of memory and language impairments in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 71, 1869–1876 (2008).

11. Piervincenzi, C. et al. Multimodal assessment of hemispheric lateralization for language and its relevance for behavior. NeuroImage 142, 351–370 (2016).

12. Silva, G. & Citterio, A. Hemispheric asymmetries in dorsal language pathway white-matter tracts: A magnetic resonance imaging tractography and functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroradiol. J. 30, 470–476 (2017).

13. Yazbek, S., Hage, S., Mallak, I. & Smayra, T. Tractography of the arcuate fasciculus in healthy right-handed and left-handed multilingual subjects and its relation to language lateralization on functional MRI. Sci. Rep. 11, 20936 (2021).

14. Zoli, M. et al. From Neurosurgical Planning to Histopathological Brain Tumor Characterization: Potentialities of Arcuate Fasciculus Along-Tract Diffusion Tensor Imaging Tractography Measures. Front. Neurol. 12, (2021).

15. Basser, P. J., Mattiello, J. & LeBihan, D. MR diffusion tensor spectroscopy and imaging. Biophys. J. 66, 259–267 (1994).

16. Basser, P. J., Mattiello, J. & LeBihan, D. Estimation of the effective self-diffusion tensor from the NMR spin echo. J. Magn. Reson. B 103, 247–254 (1994).

17. Mori, S., Crain, B. J., Chacko, V. P. & van Zijl, P. C. Three-dimensional tracking of axonal projections in the brain by magnetic resonance imaging. Ann. Neurol. 45, 265–269 (1999).

18. Tournier, J.-D. D., Calamante, F. & Connelly, A. Robust determination of the fibre orientation distribution in diffusion MRI: Non-negativity constrained super-resolved spherical deconvolution. NeuroImage 35, 1459–1472 (2007).

19. Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 785–794 (ACM, 2016). doi:10.1145/2939672.2939785.

20. Ashburner, J. et al. Statistical Parametric Mapping: The Analysis of Functional Brain Images. (2006).

21. Yushkevich, P. A. et al. User-Guided Segmentation of Multi-modality Medical Imaging Datasets with ITK-SNAP. Neuroinformatics 17, 83–102 (2019).

22. Radwan, A. M. et al. Virtual brain grafting: Enabling whole brain parcellation in the presence of large lesions. NeuroImage 229, 117731 (2021).

23. Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 62, 774–781 (2012).

24. Tourbier, S., Alemán-Gómez, Y., Griffa, A., Cuadra, M. B. & Hagmann, P. Multi-Scale Brain Parcellator: a BIDS App for the Lausanne Connectome Parcellation. F1000Research 9, (2020).

25. Radwan, A. M. et al. An atlas of white matter anatomy, its variability, and reproducibility based on constrained spherical deconvolution of diffusion MRI. NeuroImage 254, 119029 (2022).

26. Yeh, F.-C. Shape analysis of the human association pathways. NeuroImage 223, 117329 (2020).

Figures