2786

Validation of Deep Learning techniques for quality augmentation in diffusion MRI for clinical studies1Universidad de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain, 2CUBRIC, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 3University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, United States, 4Shiv Nadar University, Delhi NCR, India, 5Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 6Centre for Medical Image Computing, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 7Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, MA, United States, 8University of Sydney, Sidney, Australia, 9RWTH Aachen University, Aachen, Germany, 10University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany, 11University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 12University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, United States, 13Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 14University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States, 15New York University, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Brain, Migraine

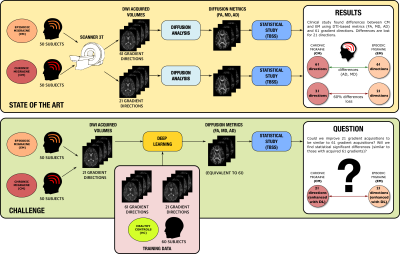

This work gathers the results of the QuadD22 challenge, held in MICCAI 2022. We evaluate whether Deep Learning (DL) Techniques are able to improve the quality of diffusion MRI data in clinical studies. To that end, we focused on a real study on migraine, where the differences between groups are drastically reduced when using 21 gradient directions instead of 61. Thus, we asked the participants to augment dMRI data acquired with only 21 directions to 61 via DL. The results were evaluated using a real clinical study with TBSS in which we statistically compared episodic migraine to chronic migraine.Introduction

Deep Learning (DL) techniques are used in medical imaging to improve quality and generate new images from reduced acquisitions. They have been a true revolution in the field, with myriads of new applications. However, most of the validation is done visually and/or qualitatively, but not adequately assessed in clinical studies to check whether differences between groups are preserved. In this work, we analyze the validity of DL in a real clinical study. We focus on a dMRI study on migraine, a pathology in which differences between groups are subtle and very dependent on the number of gradient directions. We study whether DL-based enhanced dMRI data is able to disentangle white matter alterations (WM) within pathological conditions.Materials

Two datasets are used (acquired at Hospital Clinico Universitario, Valladolid):- Training dataset: dMRI acquisition, 61 gradient directions, b=1000 s/mm2, 60 healthy controls. The sampling scheme allows the 61 directions to be subsampled to 21.

- Migraine dataset: A set of 50 Chronic migraine (CM) and 50 episodic migraine (EM) patients, all acquired with the same scheme as the training set. Teams were only provided with the 21 directions scheme. In addition, the distribution of CM-EM was blind.

Methods

Participants were asked to use an AI procedure to calculate three DTI-based parameters (FA/AD/MD) from the migraine dataset acquired with 21 directions, trying to achieve a quality similar to those estimated from 61 directions, see Figure 1 for an overview of the procedure. For evaluation, we used TBSS5 to search for differences between CM and EM. As the gold standard, we considered the results on the original data (61 directions). Voxel-wise TBSS differences in FA/AD/MD values between the two groups were tested using a permutation-based inference tool by nonparametric statistics (randomise), with the TFCE option (5000 permutations, p<0.05). We consider two quality metrics: True positives (TP) and False positives (FP).Experiments and results

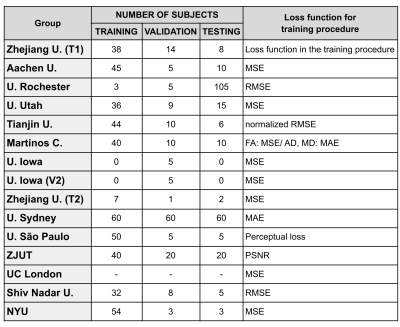

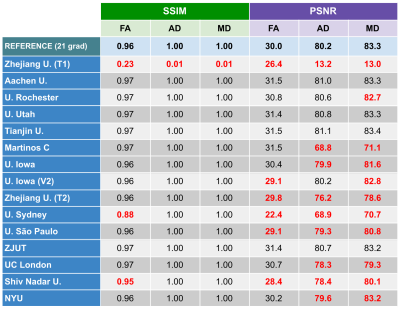

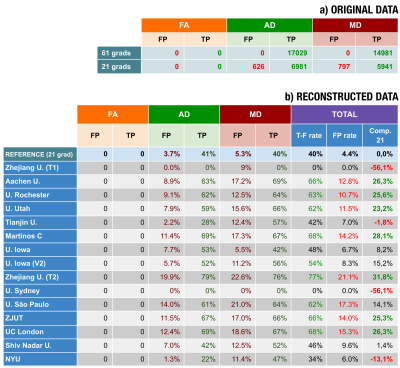

Thirteen different institutions participated in the study (14 teams and 15 methods), see Figures 2-3. All teams provided enhanced FA/AD/MD volumes for all migraine patients calculated from 21 directions. To evaluate these volumes we first considered standard image metrics: SSIM and PSNR between the enhanced images and the original data (61 directions) for the migraine patients, see Figure 4. Most methods showed a SSIM close to 1, with a very similar high performance. There is more variation in the PSNR, where most of the methods showed worse results than the reference case (21 directions). Nevertheless, most of the methods presented a very similar range of values.Second, we considered the results of the TBSS (Figure 5). In order to define a reference level, we carried out TBSS with the original data (61 directions) and later with 21 (Figure 5-a). There was a loss of 60% of the findings when reducing the number of directions. Results for the DL methods are in Fig. 5-b. We show the TP and FP rates for each metric and the following global metrics:

- True-false positive rate: $$$\text{T-F}_{\text{rate}}=\frac{\text{TP}_{\text{FA}}+ \text{TP}_{\text{AD}} +\text{TP}_{\text{MD}}}{\text{TP}_{\text{FA}} + \text{TP}_{\text{AD}} +\text{TP}_{\text{MD}}+\text{FP}_{\text{FA}} + \text{FP}_{\text{AD}} +\text{FP}_{\text{MD}}}$$$

- False positive global rate: $$$\text{FP}_{\text{rate}}=\frac{\text{FP}_{\text{FA}} + \text{FP}_{\text{AD}} +\text{FP}_{\text{MD}} }{\text{TP}_{\text{FA}(61)} + \text{TP}_{\text{AD}(61)} +\text{TP}_{\text{MD}(61)}}$$$ where $$$\text{TP}_{\text{AD}(61)}$$$ denotes the TP for the AD calculated with 61 directions.

- “Comp. 21”: increment of findings compared to the reference.

Discussion

According to Figure 4, most of the methods show similar values when using image-based metrics, like errors and perceptual measures (SSIM). Results based on these metrics did not correlate with results in the statistical test.Fig. 5 shows the results for the TBSS: four methods did not improve the reference, two methods showed slightly better results and only one method improved by over 30%. If we consider the TPs, note that most methods performed better than the reference, and eight methods found over 60% of the original points with significant differences. However, there is a counterpart: the higher the number of TPs, the higher also the number of FPs. Note that one method succeeded in finding 77% of the original points but, at the same time, it generated 21% of extra FP points. For all the methods over 60% TPs, the global FP rate is over 10%.

Regarding the different methods (see Fig. 2), it seems that those approaches that directly map FA/AD/MD into FA/AD/MD do not improve the reference. Similar results can be found for the CNN and U-Net configurations. Surprisingly, the method that did not use DL showed great performance, similar to other DL methods but with a simpler configuration.

Conclusions

For this particular dMRI case, different AI methods showed very different performance, some of them even worse than simply using the not enhanced data. Those methods that increase the number of findings (TPs) do so at the expense of also increasing the number of FPs. This is an issue of paramount importance in clinical studies, since it could have a negative impact on results. Although we cannot generalize these results to other problems, caution is advised when using DL techniques on MRI-based clinical studies.Acknowledgements

Results here presented are derived from the MICCAI 2022 challenge

QuaD22: "Quality augmentation in diffusion MRI for clinical studies: Validation in migraine", held by the CDMRI Workshop. We thank all participants.

This work was supported by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación PID2021-124407NB-I00 and TED2021-130758B-I00; European Union (NextGenerationEU), Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange for the grant PPN/BEK/2019/1/00421 under the Bekker programme, EPSRC grants M020533 R006032 R014019, Microsoft scholarship, NIHR UCLH Biomedical Research Centre, EPSRC EP/S021930/1, NIHR UCLH Biomedical Research Centre, NIHR UCLH Biomedical Research Centre, EPSRC grant EP/V034537/1, NIHR UCLH Biomedical Research Centre, Australia Medical Research Future Fund under Grant (MRFFAI000085), German Research Foundation grants ME 3737/19-1 and 269953372/GRK2150, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001, BrainsCAN and Canada Research Chairs, National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and National Institutes of Health (NIH, R01-EB028774 and R01-NS082436).

References

- Veraart, J., Novikov, D. S., Christiaens, D., Ades-aron, B., Sijbers, J., & Fieremans, E. (2016). Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory. NeuroImage, 142, 394–406.

- Andersson, J. L. R., & Sotiropoulos, S. N. (2016). An integrated approach to correction for off resonance effects and subject movement in diffusion MR imaging. NeuroImage, 125, 1063–1078.

- Tournier, J. D., Smith, R., Raffelt, D., Tabbara, R., Dhollander, T., Pietsch, M., Christiaens, D., Jeurissen, B., Yeh, C. H., & Connelly, A. (2019). MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. NeuroImage (Vol. 202).

- Smith, S. M., Jenkinson, M., Woolrich, M. W., Beckmann, C. F., Behrens, T. E. J., Johansen-Berg, H., Bannister, P. R., De Luca, M., Drobnjak, I., Flitney, D. E., Niazy, R. K., Saunders, J., Vickers, J., Zhang, Y., De Stefano, N., Brady, J. M., & Matthews, P. M. (2004). Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage, 23 (SUPPL. 1), S208–S219.

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE et al (2006) Tract-based spatial statistics: voxelwise analysis of multi- subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 31(4):1487–1505

- Ye, C., et al., An improved deep network for tissue microstructure estimation with uncertainty quantification. Medical Image Analysis 61, 101650 (2020)

- Hashemizadeh Kolowri, S.,et al., Jointly estimating parametric maps of multiple diffusion models from undersampled q-space data: A comparison of three deep learning approaches. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 87(6), 2957–2971 (2022)

- Tianshu, Z. et al. An Adaptive Network with Extragradient for Diffusion MRI-Based Microstructure Estimation. in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (2022)

- Çiçek, Ö., Abdulkadir, A., Lienkamp, S., Brox, T. & Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. LNIP (9901) (2016)

- Tang, Z., Cabezas, Z., Liu, D., Barnett, M., Cai, W. & Wang, C. LG-Net: Lesion Gate Network for Multiple Sclerosis Lesion Inpainting. LNIP (12907) (2021).

- Tang Z. et al., Diffusion MRI Fibre Orientation Distribution Inpainting, MICCAI CDMRI 2022Blumberg et al., Progressive Subsampling for Oversampled Data-Application to Quantitative MRI, MICCAI 2022.

- Blumberg et al., Progressive Subsampling for Oversampled Data-Application to Quantitative MRI, MICCAI 2022.

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; and Guo, B. 2021. Swin Transformer:Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows, Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. 2021. p. 10012-10022.

- Mani, M, Yang, B, Bathla, G, Magnotta, V, Jacob, M. Multi-band and in plane accelerated diffusion MRI enabled by model based deep learning in q-space and its extension to learning in the spherical harmonic domain. Magn Reson Med. 2022; 87: 1799 1815.

- Faiyaz, A., Uddin, M. N., & Schifitto, G. Angular upsampling in diffusion MRI using contextual HemiHex sub-sampling in q-space. arXiv, 2022, https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.00240.

Figures