2773

Longitudinal Changes in Patella Bone Shape in Subjects after ACL Reconstruction1Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, United States, 2University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States, 3Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, United States, 4Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, United States, 5University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Joints

Acute knee joint injury often leads to the development of post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA); however, the factors which may indicate PTOA progression are not well understood. Bone shape changes have been suggested as potential predictors for OA development. This study investigates longitudinal changes in patella bone shape in subjects who underwent ACL reconstruction. Subject’s patellae were segmented using machine learning methods and a statistical shape model was used to quantify patella bone shape. Data analysis showed longitudinal changes in patella shape between contralateral and ipsilateral sides, between subjects with allografts and autografts, and associations with age, sex, and BMI.Introduction

Ostoarthritis (OA) is a heterogeneous disease characterized by progressive cartilage loss, subchondral bone remodeling, osteophyte formation, and synovial inflammation which can lead to joint pain and disability and affects an estimated 250 million people worldwide1. Osteoarthritic degeneration of the joint following an acute injury, such as an articular fracture, chondral injury, or ligament or meniscal tear is termed post-traumatic OA (PTOA)2. Despite treatment, between 23-50% of individuals who suffer a knee joint trauma eventually develop PTOA and the factors which may indicate PTOA progression are not well understood3. Previous studies have investigated the time-dependent changes in the shape of the tibiofemoral joint following ACL reconstruction (ACLR), which may serve as an indicator of PTOA progression; however, similar patellofemoral joint shape changes are relatively underreported4,5. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to quantify patella bone shape in subjects who underwent ACLR and to investigate the time-dependent changes in bone shape and their associations with demographic and treatment information.Methods

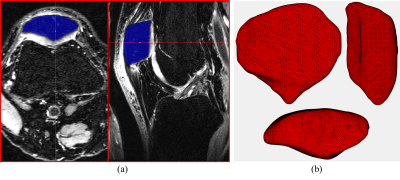

Bilateral knee MRIs from 19 subjects (10 males, age: 28.4 ± 13.6 years, BMI: 25.3 ± 1.5 kg/m2, 9 females, age: 27.7 ± 14.2 years, BMI: 25.1 ± 3.6 kg/m2) who suffered a single complete ACL injury were obtained prior to surgical reconstruction (baseline) and 6 months and 12 months following ACLR. These scans were collected as part of an IRB-approved multisite study using fat saturated 3D fast spin-echo (CUBE) sequences on 3-T MRI machines (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) and knee coils. For this study, a fully automatic segmentation pipeline was developed using 9 manually segmented scans (7 training, 2 validation). This pipeline consisted of a two stage deep leaning process where the patella bone region was first located and cropped using a 2D-UNet model and then a DenseNet based model was applied to the cropped region to obtain the bone segmentation6,7. This automatic pipeline was applied to the entire dataset and manually inspected and corrected to generate 114 patella segmentations (Figure 1a). A marching cubes algorithm was used to create 3D reconstructions from the segmented scans and Laplacian smoothing was applied to the resulting surfaces (Figure 1b)8,9. The coherent point drift method was used to register a generalized template to each patella surface, a generalized Procrustes analysis produced size invariant point distributions from the registered surfaces, and a statistical shape model was created using a principal components analysis (PCA)10,11. The first 8 PCs which explained approximately 55% of the variance in the data were retained and PC scores, which represent variations in patella shape, were collected for these factors. Several generalized linear models were fit to each of these shape variables using the generalized estimating equations (GEE) method to investigate the longitudinal changes in patella shape with side (ipsilateral vs contralateral), subject age, sex, BMI and treatment (allograft vs autograft)12. To help control for the increase in false discovery rate due to the testing of multiple hypotheses, a significance cutoff of 0.01 was chosen for this study.Results

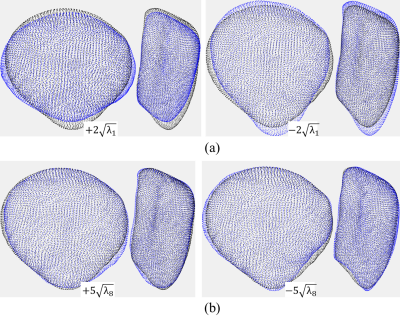

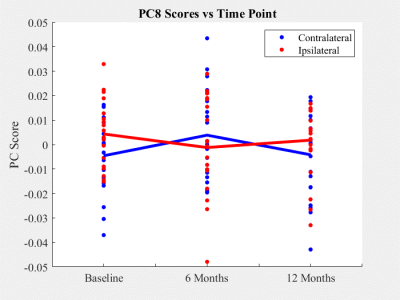

PCs 1, 3, and 5 displayed no significant association with demographic or treatment information, side, or time. PC 1, the largest shape mode, described a relative medial-lateral and proximal-distal stretching of the patella (Figure 2a). PC 8 was the only shape mode to vary significantly (p < 0.01) between contralateral and ipsilateral sides and described changes in convexity of the inferior apex and shifts of the medial and lateral margins of the patella (Figure 2b, Figure 3). Significant (p < 0.01) longitudinal patella shape changes were found to be associated with subject age (PC 6), sex (PC 7), BMI (PCs 2, 6, 8), and graft type (PCs 6, 7, 8), while overall shape changes were found to be associated with sex (PC 2), and time (PC 4).Discussion

PC 1, which accounted for approximately 15% of total patella shape variation, lacked any significant associations with time, treatment, side, or demographic information. This suggests that the largest amount of variability in patella shape was due to natural (typical) fluctuations across subjects. PC 8, accounting for approximately 3% of total variation, was the only variable to show significant longitudinal differences in patella shape between contralateral and ipsilateral sides. This indicates that a relatively small but marked amount of patella shape variability can be attributed to differential changes between contralateral and ipsilateral sides in subjects who underwent ACLR following a complete ACL injury. Additionally, several PCs were found to vary significantly with graft type pointing to a substantial impact of the choice of autograft and allograft on patella shape following ACLR.Conclusions

Significant longitudinal changes in patella shape were found to be associated with subject age, sex, BMI, graft type (autograft vs allograft), and side (contralateral vs ipsilateral) in subjects who underwent ACLR following a complete ACL injury. These results will be confirmed in a larger patient cohort in the future. We will also evaluate the relationship between patellar bone shape changes, other tissue degeneration, and patient symptoms/functions in future studies.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Arthritis Foundation.References

1. Hunter DJ, Guermazi A, Roemer F, et al. Structural correlates of pain in joints with osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013 Sep;21(9):1170-8

2. Brown TD, Johnston RC, Saltzman CL, et al. Posttraumatic osteoarthritis: a first estimate of incidence, prevalence, and burden of disease. J Orthop Trauma. 2006 Nov-Dec;20(10):739-44

3. Khella CM, Asgarian R, Horvath JM, et al. An Evidence-Based Systematic Review of Human Knee Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis (PTOA): Timeline of Clinical Presentation and Disease Markers, Comparison of Knee Joint PTOA Models and Early Disease Implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Feb 17;22(4):1996

4. Pedoia V, Lansdown DA, Zaid M, et al. Three-dimensional MRI-based statistical shape model and application to a cohort of knees with acute ACL injury. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015 Oct;23(10):1695-703

5. Zhong Q, Pedoia V, Tanaka M, et al. 3D bone-shape changes and their correlations with cartilage T1ρ and T2 relaxation times and patient-reported outcomes over 3-years after ACL reconstruction. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019 Jun;27(6):915-921

6. Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. MICCAI 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2015 Nov; 9351

7. Huang G, Liu Z, Van Der Maaten L, et al. Densely Connected Convolutional Networks. 2017 IEEE CVPR. 2017 Jul; 2261-2269

8. Lorensen WE, Cline HE. Marching cubes: A high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. ACM SIGGRAPH Computer Graphics. 1987 Jul;21(4):163-169

9. Vollmer J, Mencl R, Muller H. Improved Laplacian Smoothing of Noisy Surface Meshes. Computer Graphics forum. 1999 Sep;18(3):131-138

10. Myronenko A, Song X. Point set registration: coherent point drift. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2010 Dec;32(12):2262-75

11. Rohlf JF, Slice D. Extensions of the Procrustes Method for the Optimal Superimposition of Landmarks. Syst Zoo. 1990 Mar;39(1):40-59

12. Hardin JW, Hilbe JM (2002). Generalized Estimating Equations (1st ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC

Figures