2764

Sensitivity of Bi-Exponential UTE-T2* Mapping to Tendon Laxity1Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Tendon/Ligament, Quantitative Imaging, T2*, Bi-exponential, UTE, CONES

Tendon laxity can cause pain and increased injury risk. Quantitative MRI using Ultrashort echo time (UTE) sequences can quantify both short and long T2* water components in tendons. This study evaluates the sensitivity of UTE-T2* mapping with a bi-exponential fit model to tendon laxity, in the Achilles tendon under tension and relaxation. T2*long values seemed to increase as tendon load increased, while T2*short values were the opposite. These changes may be caused by water movement due to loading and changes in fiber orientation due to tendon slackening.Introduction

Tendon laxity, which may result in joint hypermobility or skeletal maltracking, can lead to pain and increased injury risk1. Non-invasive measurement of tendon laxity remains a challenge. Quantitative MRI using Ultrashort echo time (UTE) sequences can detect signal from tissues with short T2* relaxation times such as tendons and ligaments and are sensitive to changes in hydration as well as collagen content and organization. Further, multi-echo UTE-T2* mapping using a bi-exponential fit model can separate and quantify these components based on their relaxation mechanisms: free water (long T2*) and collagen and proteoglycan-bound water (short T2*)2-4.As tendon laxity and loading can lead to movement of water molecules within the tendon as well as differences in collagen fiber alignment, it has been suggested that laxity can be detected using T2* relaxation5-7. However, the sensitivity of T2* changes to magic angle effects, particularly in well-organized tissues such as tendons, makes this difficult to assess.

This study aims to evaluate the sensitivity of UTE-T2* mapping to tendon laxity using a bi-exponential fit model. We utilize the Achilles tendon, which aligns with the main magnetic field, under tension (ankle dorsiflexion) and relaxation (ankle planter flexion) to evaluate the sensitivity of UTE-T2* to tendon laxity.

Methods

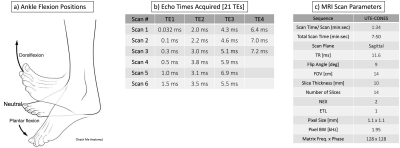

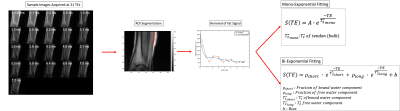

The Achilles tendons of 5 young, healthy subjects (age 26.8±2.4 years) were scanned on a 3T whole-body MRI system (GE Healthcare) using a 16-channel receive-only phased-array-coil. The imaging protocol included a sagittal spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR) scan for morphological assessment and six sagittal multi-echo UTE-Cones acquisitions, each with 4-5 echoes (21 TEs) for quantitative T2* mapping (MR scan parameters in Figure 1). All participants repeated the scanning protocol in three positions of static ankle flexion: neutral, plantar flexion, and dorsiflexion. Manual segmentation of the Achilles tendon was done to obtain a region-of-interest (ROI), and the data was averaged. To account for fat in the signal due to partial volume and chemical shift effects, chemical shift encoding (CSE)-based water-fat separation8-10 was used to isolate the signal from the tendon. The data was fit to mono-exponential and bi-exponential models for each position and subject. The fitting was performed using user-defined models in MATLAB (Figure 2). A repeated measures ANOVA was performed to measure differences across the three positions.Results

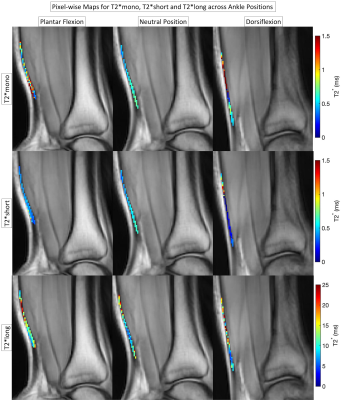

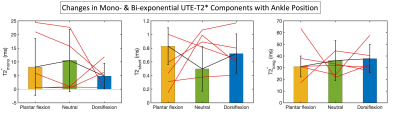

The pixel-wise T2* relaxation times of bulk, short and long water components from the mono- and bi-exponential fit analysis for one subject are shown in Figure 3. The mean T2* relaxation times from the analysis are included in Figure 4. For both mono- and bi-exponential fits, the T2* values showed changes with ankle flexion, but none of them were significant.For the mono-exponential fit, the T2*mono values increased, from plantar flexion (8.124±10.408 ms) to neutral (10.507±11.421 ms) and decreased from neutral to dorsiflexion (4.781±4.709 ms). For the bi-exponential fit, T2*short relaxation times increased in plantar flexion (0.829±0.269 ms) when compared to the neutral (0.497±0.326 ms) and dorsiflexion (0.721±0.289 ms). T2*long values decreased in plantar flexion (31.05±8.97 ms) and increased in dorsiflexion (37.77±12.14 ms) compared to the neutral position (36.14±17.05 ms). The fractions of both T2* components remained similar across all three positions, with the T2*short component accounting for over 50% of the total composition.

Discussion

We investigated the sensitivity of using UTE-T2* to changes in tendon laxity using flexion and extension of the Achilles tendon as a model. Long T2* relaxation times seemed to increase as tendon load increased, from plantar flexion (tendon relaxation) to dorsiflexion (tendon under tension). Short T2* times followed the opposite trend, with values decreasing from plantar flexion to dorsiflexion.These results may be caused by two factors: movement of water molecules in response to load and tendon orientation with respect to the main magnetic field. Previous ex vivo studies in tendons have shown a decrease in T2 values in the core with an increase in the rim of the tendon due to tensile load, potentially due to extrusion of water from the core to the periphery of the tendon5. In our experiments, we observe a bulk increase in T2*long with load during dorsiflexion.

As ankle flexion can cause changes in tendon length and fiber orientation, it is possible that T2* relaxation times, especially the T2*short values are impacted by these factors. This may explain our results where T2*short increases for plantar flexion, given that tendon fibers may align non-uniformly (in a non-parallel manner) with the main magnetic field due to slacking of tendon and reduction in length.

However, given the variability of results across subjects, these changes may also be due other factors such motion artifacts, which are visible during the flexed positions. Future work will include a bigger sample size, incorporating a uniform way of maintaining ankle flexion during scanning to reduce motion effects and inter-subject variability, and assessment of regional differences to better understand these effects.

Conclusion

UTE-T2* relaxometry appears to show some sensitivity to tendon laxity, but the scale of this effect is still unclear. Further, changes may be influenced by two competing effects, movement of water molecules in response to load and changes in tendon fiber orientation due to tendon slackening, which may require bi-exponential fitting to decouple.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research funding from GE Healthcare, NIH R21 EB030180 and R01 AR079431.References

[1] Sobel M, Geppert MJ, Warren RF. Chronic ankle instability as a cause of peroneal tendon injury. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1993 Nov(296):187-191. PMID: 8222423.

[2] Juras V, Apprich S, Szomolanyi P, Bieri O, Deligianni X, Trattnig S. Bi-exponential T2 analysis of healthy and diseased Achilles tendons: an in vivo preliminary magnetic resonance study and correlation with clinical score. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(10):2814-2822. doi:10.1007/s00330-013-2897-8

[3] Williams A, Qian Y, Chu CR. UTE-T2∗ mapping of human articular cartilage in vivo: a repeatability assessment. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2011;19(1):84-88. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2010.10.018

[4] Chu CR, Williams AA. Quantitative MRI UTE-T2* and T2* Show Progressive and Continued Graft Maturation Over 2 Years in Human Patients After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(8):2325967119863056. Published 2019 Aug 13. doi:10.1177/2325967119863056

[5] Wellen J, Helmer KG, Grigg P, Sotak CH. Spatial characterization of T1 and T2 relaxation times and the water apparent diffusion coefficient in rabbit Achilles tendon subjected to tensile loading. Magn Reson Med. 2005;53(3):535-544. doi:10.1002/mrm.20361

[6] Mountain KM, Bjarnason TA, Dunn JF, Matyas JR. The functional microstructure of tendon collagen revealed by high-field MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(2):520-527. doi:10.1002/mrm.23036

[7] Peto S, Gillis P, Henri VP. Structure and dynamics of water in tendon from NMR relaxation measurements. Biophys J. 1990;57(1):71-84. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(90)82508-X

[8] Boehm C, Diefenbach MN, Makowski MR, Karampinos DC. Improved body quantitative susceptibility mapping by using a variable-layer single-min-cut graph-cut for field- mapping. Magn Reson Med. 2021;85:1697–1712. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28515

[9] Yu H, Shimakawa A, McKenzie CA, Brodsky E, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Multiecho water-fat separation and simultaneous R2* estimation with multifrequency fat spectrum modeling. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60:1122-1134

[10] Diefenbach MN, Liu C, Karampinos DC. Generalized parameter estimation in multi-echo gradient-echo- based chemical species separation. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2020;10(3):554-567. doi: 10.21037/qims.2020.02.07

Figures