2757

Measuring Microvascular Pulsatility with Short Bolus Duration (τ) VSASL1Center for fMRI, Department of Radiology, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States, 2Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States, 3Department of Psychiatry, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States, 4Department of Bioengineering, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Arterial spin labelling, Arterial spin labelling

Pulsatile blood flow has been linked to structural damage to the cerebral microvasculature. Previous methods have successfully measured pulsatility in the arteries, but few methods exist to target the microvasculature where the damage is occurring. In this current work, we present a simple theoretical model for CBF pulsatility, apply the model to experimental data acquired in human subjects, and report in vivo microvascular pulsatility using VSASL.Introduction

Pulsatile blood flow driven by the cardiac cycle has been linked to structural damage to the cerebral microvasculature1–4, and is believed to contribute to dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and other neurovascular diseases1,2,5,6. Previous methods have used ASL or phase contrast to measure pulsatility of cerebral blood volume7–11 or flow velocity9,12–14 within the arteries, but few methods exist12 to measure pulsatility within the microvasculature where the damage is occurring. Velocity-selective ASL (VSASL) is a technique that generates perfusion contrast directly in the microvasculature15, and previous work has shown the potential of VSASL to measure the effects of cardiac pulsations16. The current work presents a theoretical model for CBF pulsatility, applies the model to experimental data acquired in human subjects, and reports in vivo microvascular pulsatility using VSASL.Theory

The control-tag subtraction signal intensity (denoted $$$S$$$) from a VSASL scan is proportional to the product of cerebral blood flow (CBF) and bolus duration $$$\tau$$$15. In the case of time-varying, pulsatile flow, we can replace the product with the following convolution:$$S(t)\propto CBF(t)\ast rect\left(\frac{t}{\tau}\right)\tag{1}$$

We see that $$$S(t)$$$ is a smoothed version of $$$CBF(t)$$$, with the degree of smoothing controlled by $$$\tau$$$. To examine cardiac-driven pulsatility, we assume a simple model for $$$CBF(t)$$$, a pure sinusoid with oscillation amplitude $$$A$$$, mean $$$B$$$, and cardiac period $$$T$$$:

$$CBF(t)=Asin\left(\frac{2\pi t}{T}\right)+B\tag{2}$$

Inserting this expression into Eq. 1 yields:

$$S(t)\propto\frac{AT}{\pi}sin\left(\frac{\pi\tau}{T}\right)sin\left(\frac{2\pi t}{T}\right)+B\tau=A\tau\cdot sinc\left(\frac{\tau}{T}\right)sin\left(\frac{2\pi t}{T}\right)+B\tau\tag{3}$$

where $$$sinc(x)=\frac{sin(\pi x)}{\pi x}$$$. To characterize pulsatility, we use a previously defined pulsatility index (PI)12–14,17. For a pulsatile signal $$$y(t)$$$ we have:

$$PI_{y(t)}=\frac{y(t)_{max}-y(t)_{min}}{y(t)_{mean}}\tag{4}$$

Applying this to $$$CBF(t)$$$ yields:

$$PI_{CBF}=\frac{2A}{B}\tag{5}$$

and to $$$S(t)$$$ yields:

$$PI_{S}=\left(\frac{2A}{B}\right)\left|sinc\left(\frac{\tau}{T}\right)\right|=PI_{CBF}\cdot\left|sinc\left(\frac{\tau}{T}\right)\right|\tag{6}$$

To account for heart rate variability, we use a modified version of Eq. 6 $$PI_{S}=PI_{CBF}\cdot\kappa(\tau)\tag{7}$$ where $$$\kappa(\tau)$$$ is the weighted average of $$$\left|sinc\left(\frac{\tau}{T}\right)\right|$$$ functions:

$$\kappa(\tau)=\sum_{i}p(T_i)\left|sinc\left(\frac{\tau}{T_i}\right)\right|\tag{8}$$

and $$$p(T_i)$$$ is the probability of observing $$$T_i$$$ for the subject.

Given Eq. 7, $$$PI_{CBF}$$$ can subsequently be estimated from a measurement of $$$PI_{S}$$$.

Methods

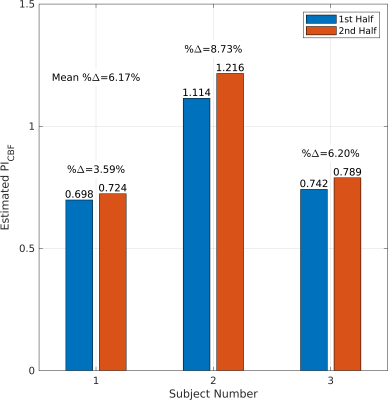

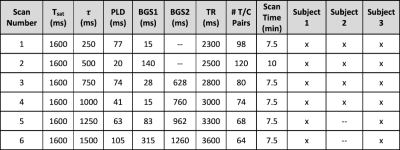

Data AcquisitionThree healthy subjects (3 males, aged 23-45 years) were scanned under UCSD IRB approval, with informed consent obtained from all participants. MRI scans were acquired on a Siemens Prisma 3.0T system with a 32ch head coil. Sessions consisted of (1) VSASL scans with $$$\tau$$$ from 250ms to ~1.5x the subject’s median $$$T$$$ in steps of 250ms, and (2) a T1-weighted MPRAGE. All VSASL scans used an identical 3D GRASE readout (resolution=4x4x6mm3, matrix size=56x56x24, single-shot, TE=15.42ms, GRAPPA acceleration 2x2 in PExSlice). See Table 1 for VS labeling and timing parameters. All VSASL scans were acquired while recording the subject’s cardiac cycle using a pulse oximeter finger cuff.

Data Processing

Motion correction of VSASL data and tissue segmentation of the T1 scan were performed using FSL18–20. The GM partial volume map was thresholded at 0.8 and resampled to the VSASL resolution to create the GM mask. Areas of bulk CSF artifact were manually excluded. Using this final mask, mean GM signal intensity was extracted from each VSASL timepoint.

Pulsatility Analysis

Pulse oximeter signals were smoothed, followed by peak detection. Following previously described approaches8,9,11, a fractional cardiac phase was assigned to each volume, data were fit to a 2nd-order Fourier function, and $$$PI_{S}$$$ was computed for each VSASL scan via Eq. 4.

To assess agreement with our model, $$$\kappa(\tau)$$$ was calculated via Eq. 8, with $$$p(T_i)$$$ estimated from the distribution of $$$T$$$s from the pulse oximeter signal. Then, each subject’s $$$PI_{S}$$$ vs $$$\tau$$$ data were fit to Eq. 7. To assess repeatability, each subject’s $$$\tau=500ms$$$ scans were also split into two halves and $$$PI_{CBF}$$$ was estimated from $$$PI_{S}$$$ with Eq. 7 for each half. Percent difference in $$$PI_{CBF}$$$ between each half was then computed.

Results

Figure 1 shows $$$PI_{S}$$$ vs $$$\tau$$$ for each subject and the fit of their data to Eq. 7. The local minimum of $$$PI_{S}$$$ around $$$\tau=T$$$ is an important validation that we are measuring cardiac-driven pulsatility, since from Eq. 3 we expect little fluctuation in $$$S$$$ when $$$\tau$$$ is exactly one cardiac period.Figure 2 shows the estimated $$$PI_{CBF}$$$ values from the two halves of the $$$\tau=500ms$$$ scans to test repeatability. We have good repeatability with this configuration, with a mean percent difference of 6.17% between successive halves.

Discussion

To our knowledge, we report the first measurement of CBF pulsatility within the microvasculature by exploiting the unique microvascular specificity of VSASL.Reflecting the effect of the $$$sin(\pi\frac{\tau}{T})$$$ term in Eq. 3, the fluctuation amplitude of $$$S$$$ is maximized with $$$\tau=T/2$$$, making it optimal for measuring $$$PI_{S}$$$. For a typical $$$T$$$ near 1s, $$$\tau=500ms$$$ satisfies this criterion.

The microvascular pulsatility we observe is presumably driven by signal changes slightly upstream, supported by Franklin et al. showing cardiac-driven signal changes up to 36% in the VS-labeled arterial pool16. Notably, Bouvy et al. reported lower PI values in the microvasculature12 than our current work; however, they measured PI on flow velocity, as opposed to CBF, which may explain this discrepancy. Future work will consider more physiologically realistic waveforms for $$$CBF(t)$$$, and refine our treatment of heart-rate variability by incorporating it earlier in our theory into $$$CBF(t)$$$. Both improvements will facilitate better modeling of downstream effects on pulsatility measurements.

Conclusion

We have established a novel, repeatable approach of using VSASL to measure CBF pulsatility in the microvasculature.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Mitchell, G. F. Effects of central arterial aging on the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature: Implications for end-organ damage. Journal of Applied Physiology vol. 105 1652–1660 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.90549.2008 (2008).

2. Mitchell, G. F. et al. Arterial stiffness, pressure and flow pulsatility and brain structure and function: The Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study. Brain 134, 3398–3407 (2011).

3. Henskens, L. H. G. et al. Increased aortic pulse wave velocity is associated with silent cerebral small-vessel disease in hypertensive patients. Hypertension 52, 1120–1126 (2008).

4. Duprez, D. A. et al. Relationship between periventricular or deep white matter lesions and arterial elasticity indices in very old people. (2001).

5. Zarrinkoob, L. et al. Aging alters the dampening of pulsatile blood flow in cerebral arteries. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 36, 1519–1527 (2016).

6. Mills, S., Cain, J., Purandare, N. & Jackson, A. Biomarkers of cerebrovascular disease in dementia. British Journal of Radiology vol. 80 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/79217686 (2007).

7. Yan, L., Li, C., Kilroy, E., Wehrli, F. W. & Wang, D. J. J. Quantification of arterial cerebral blood volume using multiphase-balanced SSFP-based ASL. Magn Reson Med 68, 130–139 (2012).

8. Pahlavian, S. H., Jog, M., Ma, S., Wang, D. J. J. & Yan, L. Quantification of intracranial vascular compliance using multi-PLD pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling with retrospective cardiac gating. ISMRM Abstract 1064, 156687 (2019).

9. Li, Y. et al. Three-dimensional assessment of brain arterial compliance: Technical development, comparison with aortic pulse wave velocity, and age effect. Magn Reson Med 86, 1917–1928 (2021).

10. Yan, L. et al. Assessing intracranial vascular compliance using dynamic arterial spin labeling. Neuroimage 124, 433–441 (2016).

11. Warnert, E. A. H., Murphy, K., Hall, J. E. & Wise, R. G. Noninvasive assessment of arterial compliance of human cerebral arteries with short inversion time arterial spin labeling. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 35, 461–468 (2015).

12. Bouvy, W. H. et al. Assessment of blood flow velocity and pulsatility in cerebral perforating arteries with 7-T quantitative flow MRI. NMR Biomed 29, 1295–1304 (2016).

13. Heidari Pahlavian, S. et al. Assessment of carotid stiffness by measuring carotid pulse wave velocity using a single-slice oblique-sagittal phase-contrast MRI. Magn Reson Med 86, 442–455 (2021).

14. Pahlavian, S. H. et al. Cerebroarterial pulsatility and resistivity indices are associated with cognitive impairment and white matter hyperintensity in elderly subjects: A phase-contrast MRI study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 41, 670–683 (2021).

15. Qin, Q. et al. Velocity‐selective arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI: A review of the state of the art and recommendations for clinical implementation. Magn Reson Med 88, 1528–1547 (2022).

16. Franklin, S. L., Schmid, S., Bos, C. & van Osch, M. J. P. Influence of the cardiac cycle on velocity selective and acceleration selective arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med 83, 872–882 (2020).

17. Shi, Y. et al. Small vessel disease is associated with altered cerebrovascular pulsatility but not resting cerebral blood flow. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 40, 85–99 (2020).

18. Jenkinson, M., Beckmann, C. F., Behrens, T. E. J., Woolrich, M. W. & Smith, S. M. FSL. Neuroimage 62, 782–790 (2012).

19. Woolrich, M. W. et al. Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage 45, (2009).

20. Smith, S. M. et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. in NeuroImagevol. 23 (2004).

21. Wong, E. C. et al. Velocity-selective arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med 55, 1334–1341 (2006).

Figures