2709

Using BOLD-fMRI to Compute Respiration Volume per Time (RVT) and Respiration Variation (RV) with Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) in Children1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Schulich School of Engineering, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2Hotchkiss Brain Institute, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 3Department of Radiology, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 4Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 5Department of Medical Physics, Alberta Heath Services, Calgary, AB, Canada, 6Department of Electrical & Software Engineering, Schulich School of Engineering, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Processing, fMRI, Physiological Noise

In many fMRI studies, respiratory signals are unavailable or do not have acceptable quality. Consequently, the direct removal of low-frequency respiratory variations from BOLD signals is not possible. This study proposes a one-dimensional CNN model for reconstruction of two respiratory measures including RV and RVT. Results show that a CNN can capture informative features from the BOLD signals and reconstruct accurate RV and RVT timeseries. It is expected that application of the proposed method will lower the cost of fMRI studies, reduce complexity, and decrease the burden on participants because they will not be required to wear a respiratory bellowsIntroduction

Low-frequency variation in breathing rate and depth during functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning can alter cerebral blood flow and consequently the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal. Over the past decade, respiratory response function models [1-4] have shown good performance in modelling the confounds induced by low-frequency respiratory variation. While convolution models perform well, they require the collection of external signals that can be cumbersome and prone to error in the MR environment.Respiratory data is not routinely recorded in many fMRI experiments due to the absence of measurement equipment in the scanner suite, insufficient time for set-up, financial concerns, or any other reason [5-7]. Even in the studies where respiratory timeseries is measured, a large portion of the recorded signals don’t have acceptable quality, particularly in pediatric populations [8]. This work proposes a method for estimation of the two main respiratory timeseries used to correct fMRI, including respiration variation (RV) and respiratory volume per time (RVT), directly from BOLD fMRI data.

Method

In this study, we used resting-state fMRI scans and the associated respiratory belt traces in Human Connectome Project in Development (HCP-D) dataset (from HCD0001305 to HCD2996590), where participants are children in the age range of 5 and 21 years [9, 10]. From 2451 scans, 306 scans were selected based on the quality of their respiratory signals. Figure 1 shows some examples of the usable scans (12.4%) and unusable scans (87.6%).The RVT is the difference between the maximum and minimum belt positions at the peaks of inspiration and expiration, divided by the time between the peaks of inspiration [1], and RV is defined as the standard deviation of the respiratory waveform within a six-second sliding window centered at each time of point [11].

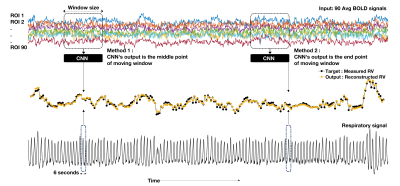

In the proposed method a CNN is applied in the temporal dimension of the BOLD time series for RV and RVT reconstruction. To decrease computational complexity, the average BOLD signal time series from 90 functional regions of interest (ROI) [12] were used as the main inputs. Figure 2 shows the model input and output for RV estimation. For each RV point, BOLD signals centered at the RV point covering 32 TRs before and after were used as the input. The output of the model can be defined as any point of the moving window. In this paper, we implemented two approaches: middle point of the window (Method 1 in Figure 1), and end point of the window (Method 2 in Figure 1). In Method 1, CNN can use both past and future information, but in Method 2 it can only use the past information hidden in the BOLD signals. The same procedure is applied for RVT estimation.

A ten-fold cross-validation strategy was employed to evaluate the robustness of the proposed model. The performance of each fold was evaluated based on mean absolute error (MAE), mean square error (MSE), coefficient of determination of the prediction (R2), and dynamic time warping (DTW).

Results

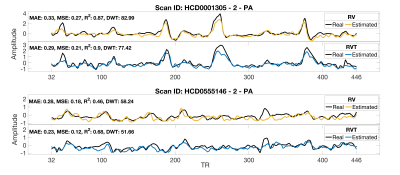

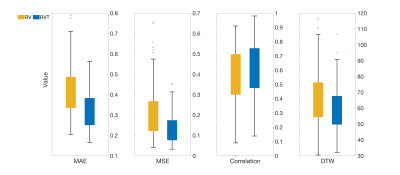

Figure 3 shows the performance of the proposed method considering the middle point of the window as the network’s output on two samples from the test subset. The trained network can reconstruct the RV and RVT timeseries well, especially when there are big changes in RV and RVT value. Large changes in RV and RVT can happen when the subject has a deep breath or changes their breathing pattern. Variations in breathing pattern induce a confound to the BOLD signal and the CNN model can use that information to reconstruct the RV and RVT timeseries.Figure 4 shows the performance of the CNN considering the middle point of the window as the CNN’s output in terms of MAE, MSE, correlation, and DTW. As the performance is a function of the variation, no one performance metric is satisfactory.

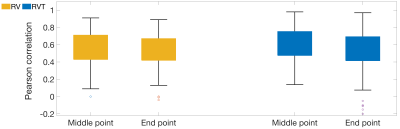

Figure 5 shows the impact of output point location, whether estimating the point at the middle or end of the window, on network’s performance. The obtained results showed that using both sides, before and after the current breath, leads to better performance.

Discussion

The current work demonstrates the ability to compute both the RV and RVT signals from the fMRI data alone in a pediatric population, which eliminates the need for external respiratory measurement device and reduces cost.In this paper we used window size 64, but this is an adjustable parameter. Larger window sizes provide more information about baseline breathing rate and depth, and enable the model to better estimate variation. An important limitation of larger window size is that they result in more timepoints discarded at the beginning and end of the scan due to edge-effects. This may limit the minimum duration of scans that can be reasonably reconstructed with the proposed approach, but for longer scans a larger window might be acceptable. For fMRI studies with short scan times, the proposed method using a window size of 16 or 32 will be a reasonable choice with a fair performance.

There is potential to enrich a large volume of existing resting-state fMRI datasets through retrospective addition of respiratory signal variation information, which is an interesting potential application of the developed method.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of Calgary, in particular the Schulich School of Engineering and Departments of Biomedical Engineering and Electrical & Software Engineering; the Cumming School of Medicine and the Departments of Radiology and Clinical Neurosciences; as well as the Hotchkiss Brain Institute, Research Computing Services and the Digital Alliance of Canada for providing resources. The authors would like to thank the Human Connectome Project for making the data available. JA – is funded in part from a graduate scholarship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Brain Create. GBP acknowledges support from the Campus Alberta Innovates Chair program, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (FDN-143290), and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (RGPIN-03880). MEM acknowledges support from Start-up funding at UCalgary and a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant (RGPIN-03552) and Early Career Researcher Supplement (DGECR-00124).References

1. Birn, R.M., et al., Separating respiratory-variation-related fluctuations from neuronal-activity-related fluctuations in fMRI. NeuroImage, 2006. 31(4): p. 1536-1548.

2. Chang, C. and G.H. Glover, Relationship between respiration, end-tidal CO2, and BOLD signals in resting-state fMRI. NeuroImage, 2009. 47(4): p. 1381-1393.

3. Golestani, A.M., et al., Mapping the end-tidal CO2 response function in the resting-state BOLD fMRI signal: Spatial specificity, test–retest reliability and effect of fMRI sampling rate. NeuroImage, 2015. 104: p. 266-277.

4. Wise, R.G., et al., Resting fluctuations in arterial carbon dioxide induce significant low frequency variations in BOLD signal. NeuroImage, 2004. 21(4): p. 1652-1664.

5. Mascarell Maričić, L., et al., The IMAGEN study: a decade of imaging genetics in adolescents. Molecular Psychiatry, 2020. 25(11): p. 2648-2671.

6. Miller, K.L., et al., Multimodal population brain imaging in the UK Biobank prospective epidemiological study. Nature Neuroscience, 2016. 19(11): p. 1523-1536.

7. Shafto, M.A., et al., The Cambridge Centre for Ageing and Neuroscience (Cam-CAN) study protocol: a cross-sectional, lifespan, multidisciplinary examination of healthy cognitive ageing. BMC Neurol, 2014. 14: p. 204.

8. Smith, S.M., et al., Resting-state fMRI in the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage, 2013. 80: p. 144-168.

9. Harms, M.P., et al., Extending the Human Connectome Project across ages: Imaging protocols for the Lifespan Development and Aging projects. NeuroImage, 2018. 183: p. 972-984.

10. Somerville, L.H., et al., The Lifespan Human Connectome Project in Development: A large-scale study of brain connectivity development in 5–21 year olds. NeuroImage, 2018. 183: p. 456-468.

11. Chang, C., J.P. Cunningham, and G.H. Glover, Influence of heart rate on the BOLD signal: The cardiac response function. NeuroImage, 2009. 44(3): p. 857-869.

12. Shirer, W.R., et al., Decoding subject-driven cognitive states with whole-brain connectivity patterns. Cereb Cortex, 2012. 22(1): p. 158-65.

Figures