2702

Reducing the number of virtual observation points when utilizing populations of body models1A. A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA, United States, 2Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Erwin L. Hahn Institute for MRI, University Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany, 4High-Field and Hybrid MR Imaging, University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany, 5Institute of Medical Physics and Radiation Protection, Department of Life Science Engineering, Mittelhessen University of Applied Sciences, Giessen, Germany, 6Center for Mind, Brain and Behavior (CMBB), Philipps-University Marburg, Marburg, Germany, 7Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: RF Pulse Design & Fields, RF Pulse Design & Fields

We introduce a VOP compression scheme using “stacked E-fields” followed by the removal of linear redundancies with a positive semi-definite convex optimization problem. This method provides a lower VOP-count at a constant SAR overestimation factor compared to three other approaches when applied to 7 Tesla 8-channel and 16-channel arrays loaded with three body models, each placed at three z-positions. The “stacked E-field” method yielded a compression factor of 0.0124% and 0.0039% for the 8-channel and 16-channel arrays, respectively, and 61% and 6% fewer VOPs than the standard VOP approach that does not remove linear redundancies.Introduction

Parallel transmission (pTx) creates complex E-field interferences between transmit channels that require monitoring in real-time during the MRI sequence. This is typically done by simulation of multiple body models and positions and compression of the resulting Q-matrices1 using the virtual observation points (VOPs) algorithm2. Despite relatively high compression factors, VOP sets routinely have hundreds of control matrices which can prove challenging for rapid (millisecond timescale) specific absorption rate (SAR) monitoring. Similarly, patient-specific pulse optimization including SAR metrics requires a reduced VOP count while keeping the SAR overestimation factor as small as possible. In this study, we compared four VOP compression approaches that each produce different numbers of VOPs for the same SAR overestimation factor and describe an optimal method.Methods

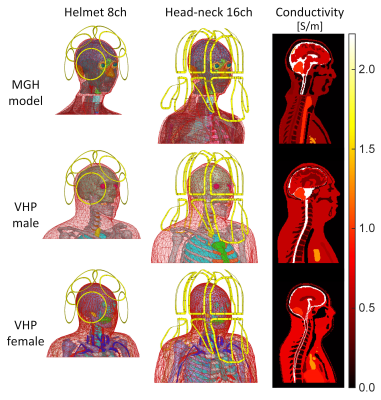

We simulated a 7T 8-channel helmet pTx head array3 and a 16-channel pTx head/neck array4 (Figure 1). Each coil was loaded with three body models (MGH model5,6, VHP male7, and VHP female8), which all contain significant cerebrospinal fluid compartments. Numerical electromagnetic (EM) simulations were performed with ANSYS Electronics (ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA). The co-simulation approach was employed for efficient tuning, matching and decoupling (matching <-20dB and coupling <-10dB). Each body model was modeled at z=0 (eyes at iso-center), z=-10mm, and z=+10mm, to provide robustness of the virtual observation point set with respect to subject position and motion.The E-fields and B1+-maps of each channel were exported on 2-mm isotropic grids covering the head, neck, and shoulders. 10g-averaged SAR Q-matrices were computed and compressed using the VOP algorithm2 with a maximum SAR overestimation factor of 5×10-4 W/kg/V2 for the 8-channel array and 7.5×10-4 W/kg/V2 for the 16-channel array.

We compare four VOP approaches: 1) computation of VOPs for each body model/position followed by concatenation of the VOP files, 2) concatenation of E-fields for all body models/positions, followed by VOP compression. Methods 3) and 4) are the same as 1) and 2), but are followed by a “generalized VOP” (gVOP) step proposed by Lee et al9 which is based on the observation that the original VOP approach creates VOPs dominated (in the semi-definite positive sense) by linear combinations of all other VOP matrices in the set. For those VOPs (Sj), it is possible to find real numbers λ1,…,λN, such that

$$\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}{{\rm{gVOP\; \; condition}}:}&{\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}{\sum\limits_{i = 1,..,\,N\atop\,\,\,\,i\ne j}{{\lambda_i}{{\bf{S}}_i}} \succ {{\bf{S}}_j}{\rm{ }}}\\{where\,\sum\limits_{i = 1,..,\,N\atop\,\,\,\,i\ne j}{{\lambda_i}}=1+\varepsilon}\end{array}}&{}&{[1],}\end{array}$$

where ε is the maximum SAR overestimation factor expressed as a percentage of the worst possible local-SAR for a unit pulse. Matrices Sj satisfying condition [1] should be removed from the set. We used the semi-definite MATLAB program SeDuMi10 interfaced with YALMIP11 to solve the gVOP condition.

Results

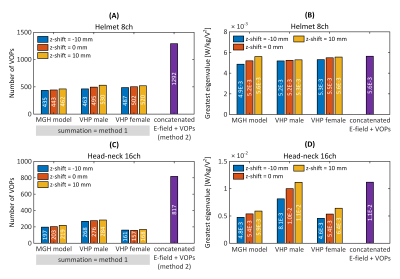

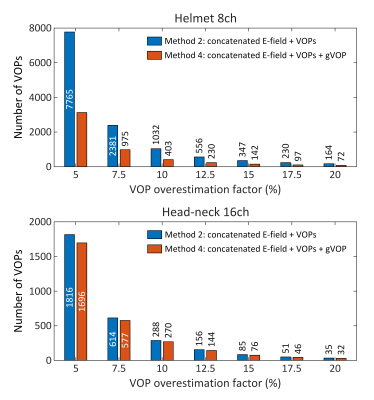

Figures 2A-C show the number of VOPs for all coils, body models and positions (method#1), as well the number of VOPs obtained by concatenation of E-fields for all body model positions, followed by VOP compression (method#2). Method#1 yielded 4337 and 1933 VOPs for the 8-channel and 16-channel coils, respectively, whereas method#2 yielded 1292 and 817 VOPs for those coils; a 70% and 58% reduction in the number of VOPs for the same SAR overestimation factor. Therefore, the VOP algorithm should always be run on concatenated E-fields, and not on individual model E-fields followed by concatenation of the resulting VOP sets. Figures 2B-D show that the maximum eigenvalue (worst-case local-SAR) of individual models/positions (method#1) is equal to that of the concatenated E-field + VOP (method#2), showing that, as expected, the VOP algorithm captures worst-case SAR combinations without information loss across body models and positions.Figures 3A-4A show the number of VOPs associated methods#1-4 for the 8-channel and 16-channel arrays. For both arrays, method#4 (“concatenated E-field + VOPs + gVOP”) yielded the smallest number of the VOPs at constant SAR overestimation. The impact of the gVOP step was much more pronounced for the 8-channel than the 16-channel array, although the reason for that is still under investigation. Figures 3B-4B show that all VOP sets yields SAR overestimations within the prescribed limit, which validates the different methods (they only differ by their compression ratio).

Figure 5 shows that the impact of the gVOP step increases at low SAR overestimation factors. This signifies that VOP sets with stringent epsilon SAR overestimation values have a greater tendency to create redundant control matrices, and therefore benefit more from VOP pruning by solving Eq. [1]. This phenomenon was much more pronounced for the 8-channel than the 16-channel array.

Discussion

MRI manufacturers limit the size of VOP files used by the safety watchdog to guarantee that SAR monitoring is fast enough12. There is a tradeoff between the number of VOPs and SAR estimation accuracy: small files may lead to large SAR overestimation, which is undesirable as this yields SAR-inefficient RF pulses and protocols. We found that the best compression strategy applies the VOP compression after concatenation of the E-fields of different body models/positions. Even then, however, a significant number of linear redundancies remain in the set, which we were able to remove by solving the generalized VOP condition [1]. Doing so further reduced the VOP sets by 61% for the 8-channel coil and 6% for the 16-channel coil while keeping the SAR overestimation factor constant.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Guerin B, Gebhardt M, Cauley S, et al. Local specific absorption rate (SAR), global SAR, transmitter power, and excitation accuracy trade-offs in low flip-angle parallel transmit pulse design. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(4):1446-1457.

2. Eichfelder G, Gebhardt M. Local specific absorption rate control for parallel transmission by virtual observation points. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(5):1468-1476.

3. Kazemivalipour E, Wald LL, Guerin B. Comparison of simulated parallel transmit head arrays at 7T using excitation uniformity, local SAR, and global SAR. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med 30 2022:5048.

4. May MW, Hansen SJD, Mahmutovic M, et al. A patient-friendly 16-channel transmit/64-channel receive coil array for combined head-neck MRI at 7 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2022;88(3):1419-1433.

5. Massire A, Cloos MA, Luong M, et al. Thermal simulations in the human head for high field MRI using parallel transmission. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35(6):1312-1321.

6. Makris N, Angelone L, Tulloch S, et al. MRI-based anatomical model of the human head for specific absorption rate mapping. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2008;46(12):1239-1251.

7. Noetscher GM. The CAD-Compatible VHP-Male Computational Phantom. In Makarov SN, Noetscher GM, Nummenmaa A, (Eds). Brain and Human Body Modeling 2020: Computational Human Models Presented at EMBC 2019 and the BRAIN Initiative(R) 2019 Meeting. Cham (CH) 2021:309-323.

8. Makarov SN, Noetscher GM, Yanamadala J, et al. Virtual Human Models for Electromagnetic Studies and Their Applications. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2017;10:95-121.

9. Lee J, Gebhardt M, Wald LL, et al. Local SAR in parallel transmission pulse design. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(6):1566-1578.

10. Sturm JF. Using SeDuMi 1.02, A Matlab toolbox for optimization over symmetric cones. Optimization Methods and Software. 1999:625-653.

11. Lofberg J. Yalmip : a toolbox for modeling and optimization in MATLAB. In: . IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation 2004:284–289.

12. Jin J, Weber E, Destruel A, et al. An open 8-channel parallel transmission coil for static and dynamic 7T MRI of the knee and ankle joints at multiple postures. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79(3):1804-1816.

Figures