2701

On the Importance of Solving for Temperature Versus Local SAR When Evaluating RF-Induced Heating in the Magnetic Resonance Environment

Eric David Anttila1, Grant M Baker1, Alan R Leewood1, and David C Gross1

1MED Institute, West Lafayette, IN, United States

1MED Institute, West Lafayette, IN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Safety, Safety

Previous work has determined that solving for a weighted average local SAR is a relatively easy to way to estimate worst-case RF-induced heating in MRI. The purpose of this study was to determine the importance of solving for temperature using a sequentially coupled electromagnetics and heat transfer model versus local SAR alone when evaluating worst-case RF-induced heating. The results demonstrate that to fully capture RF-induced heating in MRI, temperature rise must be solved for using a sequentially coupled electromagnetic and heat transfer model due to the complex interplay of electric and thermal material properties for implants and the surrounding tissue.Introduction

When a patient with a metallic implant is scanned in an MRI environment, the body transmit radiofrequency (RF) coil induces eddy currents onto the implant, resulting in heating of the tissue adjacent to the implant. One of the primary methods for evaluating RF-induced heating in the MRI environment is by using computational analysis (e.g., finite element method) in order to solve the electromagnetics to evaluate local specific absorption rate (SAR) or the sequentially coupled electromagnetics and heat transfer to evaluate temperature rise. It has been previously hypothesized that solving for a weighted average local SAR is a relatively easy to way to estimate worst-case RF-induced heating. The purpose of this work was to determine the importance of solving for temperature using a sequentially coupled electromagnetics and heat transfer model versus local SAR alone when evaluating worst-case RF-induced heating in the MRI environment.Methods

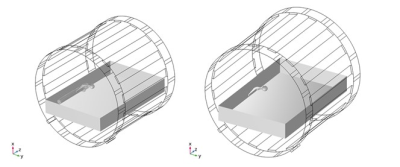

COMSOL Multiphysics® was used to build a computational model of a 1.5 T Siemens Altea conventional RF birdcage coil. Geometric details of the coil design were provided by Siemens. Validation of the computational model included titanium calibration rods in the ASTM F2182 phantom. Input voltages for the simulations were tuned to achieve a whole phantom SAR of 2 W/kg. The sequentially coupled electromagnetics and heat transfer problems were solved. RF-induced heating simulating a 15-minute scan of a representative hip implant within the Duke Virtual Human Anatomy’s femur in the ASTM phantom gel and in the ASTM phantom gel only were conducted, as shown in Figure 1. The gel phantom was assumed to be a solid, therefore convective heat transfer in the gel was not considered since the viscosity of the gel prevents bulk fluid motion. The hip stem was placed 2 cm from the side of the ASTM phantom at mid-depth, as higher heating is associated with this location. Local SAR was averaged over several spherical volumes to provide a weighted average (0.1 g, 1 g, 10 g) for each simulation and compared with temperature rise.Results

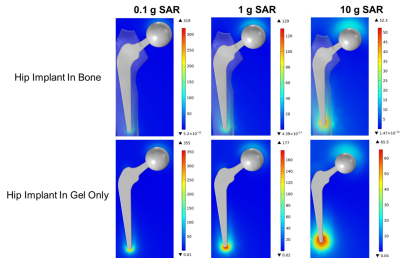

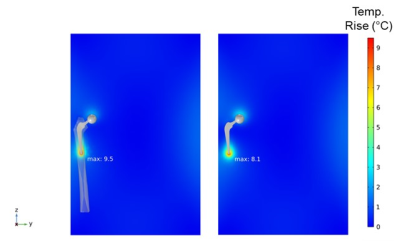

Different weighted averages of local SAR were compared by simulating a 15-minute scan of a representative hip implant within the Duke Virtual Human Anatomy’s femur in the ASTM phantom gel and in the ASTM phantom gel only in the 1.5 T Siemens Altea conventional RF birdcage coil. As expected, the local SAR changes significantly based on the weighted average, amongst other factors, as shown in Figure 2. When comparing the 1 g weighted average local SAR, the simulation of the representative hip implant within the Duke Virtual Human Anatomy’s femur in the ASTM phantom gel demonstrates a maximum of 129 W/kg, while the simulation of the representative hip implant in the ASTM phantom gel demonstrates a maximum of 177 W/kg (31% higher). However, when comparing temperature rises, the representative hip implant within the Duke Virtual Human Anatomy’s femur in the ASTM phantom gel shows a 16% higher temperature rise (9.5°C) than the representative hip implant in the ASTM gel phantom only (8.1°C), as shown in Figure 3.Discussion and Conclusion

The results herein demonstrate that in order to fully capture RF-induced heating in the MRI environment, temperature rise must be solved for using a sequentially coupled electromagnetic and heat transfer model due to the complex interplay of electric and thermal material properties for implants and the surrounding tissue. Moreover, the finite element software solves the full-field electromagnetics in all domains (i.e., everywhere) and it is challenging to use SAR as an intermediate metric for temperature rise due to the sensitivity of SAR near an electrically conductive medical device. However, evaluation of local SAR may be sufficient to determine worst-case RF-induced heating if all other properties of the simulation are maintained (e.g., determining worst-case hip implant with various sizes within the ASTM gel phantom).Acknowledgements

The authors also would like to thank Siemens Healthineers (Erlangen, Germany) for providing information regarding their RF coil. The authors also thank AltaSim Technologies (Columbus, OH) for their help with the development and validation of the RF coil model in COMSOL Multiphysics®.References

No reference found.Figures

Model

setup showing the conventional RF birdcage coil with a representative

hip implant within the Duke Virtual Human Anatomy’s femur in the ASTM phantom

gel (left) and in the ASTM phantom gel only (right).

0.1

g, 1 g, and 10 g weighted local SAR contour plots (units: W/kg) for the

representative hip implant within the ASTM gel phantom with the implant inside

of the Duke Virtual Human Anatomy’s femur (top) and in the presence of gel only

(bottom).

Temperature rises due to RF-induced heating of the

representative hip implant within the ASTM gel phantom with the implant inside

of the Duke Virtual Human Anatomy’s femur (left) and in the presence of gel

only (right).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2701