2694

Experimental Validation of Deep Learning Based Local SAR Mapping from 3D B1+ and Localizer-like MRIs for 7T pTx Systems

Sayim Gokyar1, Chenyang Zhao1, and Danny JJ Wang1,2

1USC Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Department of Neurology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

1USC Stevens Neuroimaging and Informatics Institute, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2Department of Neurology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Safety, Safety, Local SAR Prediction

Local SAR related heating is a limiting safety factor at UHF MRI. Since local SAR cannot be measured, it should either be estimated from the global SAR or predicted by using the available data such as B1+ maps and MRIs. Here we proposed to use a multi-channel 3D CNN to utilize different channels for B1+ maps and MRIs simultaneously to improve local SAR prediction. We validated our method on 6 participants and found that maximum SAR values can be predicted with 80% accuracy, and local SAR variation can be predicted over 95% accuracy by using common image similarity metrics.Introduction

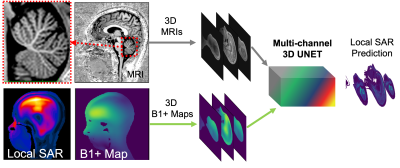

Ultra-high field (UHF) MRI (≥7T) offers improved signal to noise ratio (SNR), but it comes at the cost of increased specific absorption rate (SAR) and higher local SAR variation in human anatomy due to wavelength effect1,2. With the advancement of parallel transmission (pTx) technology at UHF MRI3, radio-frequency (RF) fields become more complex than ever for clinical settings due to constructive and destructive interferences1. Convolutional neural networks (CNN) were utilized before to predict local SAR distributions from B1+ maps4 or MRI-like images5. However, B1+ based methods suffer from the lack of anatomy details, and MRI-like method does not include field distributions to predict local SAR. Hence, both methods result in compromised accuracy. A new approach, which uses CNNs for tissue segmentations and then calculates the local SAR, showed promising results in clinical settings6,7. But this approach requires the solutions of electromagnetic fields after imaging, which might be difficult for implementation by clinicians or radiologists.Here we present an improved method to predict local SAR distribution directly from the scanner data (i.e., B1+ maps and localizer-like images simultaneously, Figure-1), avoiding the modeling of patients and full-wave simulations, thus allows for seamless integration in clinical practice. We validated this method on six participants.

Methods

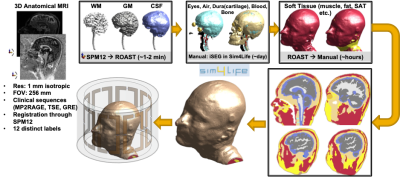

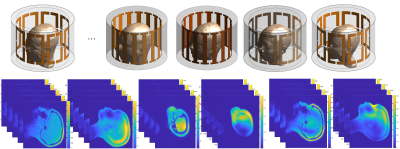

A multi-channel three-dimensional (MC-3D) UNET structure composed of 4 contraction layers and having 64 filters in the first stage as described before was utilized5. Sim4Life8 with two realistic body models (Duke and Ella) from the library of IT’IS9 were used. We scanned six volunteers (age of 31±4.1 years, four males and two females) with MP2RAGE sequence (1mm isotropic resolution) by using Siemens Terra 7T scanner to generate new head models by using iSEG module in Sim4Life (Figure 2). An eight-channel pTx loops and an 8-channel driven birdcage coils constructed in the numerical environment. Additionally, participants scanned by using 8 channel Nova pTx head coil with a 3D-GRE sequence (TR/TE: 12/1.1 ms, ⍺=5-15°, 2mm isotropic resolution with an FOV:256mm, total acquisition time of 12 s) with different channel weights adjusted randomly. These total of 161 3D-images converted to Nifti for co-registration by using SPM12. Co-registered images were later converted to h5 format and normalized to their maximums for CNN training.10g-averaged SAR maps were calculated for the corresponding experimental B1+ of each body model and iteration (Figure 3). Generated data was augmented by randomly flipping and rotating the iterations (i.e., 161 experimental 3D scans) and randomly split with a ratio of 70-15-15% for training, validation, and testing. A weighted mean absolute error was used as the loss function during training. Structural similarity index (SSIM)9, feature similarity index (FSIM)10, and mean squared error (MSE) were evaluated for the resulting prediction maps. Algorithms initially trained and tested on numerical body models only and then the experimental data were incorporated to studies.

Results

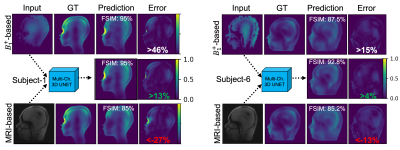

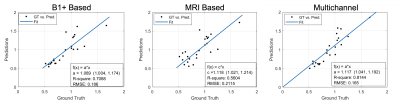

Training and testing of the algorithms took 0.7 and 0.1 s per 3D data on an Nvidia 3080-Ti graphical processing unit, respectively. Figure 4 shows that the MC-3D-UNET trained on simulated B1+ maps predicted 10g-averaged local SAR distribution with an SSIM of 97.1±1.9%, FSIM of 97.4±1.8%, and MSE of <0.1%. Instead of full field-of-view, when the region of interest was masked to head location, then the mean SSIM drops to 90.8% and mean FSIM becomes 97.5%, showing the robustness of FSIM over SSIM for images with mainly zero-filled pixels. When we tested these weights with experimental data, we have seen that performances drop to 70% for SSIM and FSIM, and errors increased above 10% for MSE due to noise, and low-resolution B1+ fields. Incorporating experimental data to trainings improved FSIM to >89.1% for B1+ only training, and >86.3% for MRI-based training. MB-3D-CNN achieved an average FSIM of >94.4% and an average error of <0.4% for all experimental models. Figure 5 shows that multichannel approach achieved the better reliability (81.4% goodness of the fit) with reasonable overestimation error (i.e., 11.8% average and 65% maximum overestimation error).Discussion

CNN-based predictions based on simulations did not work on experimental data due to poor representation of physiology in simulations, low resolution B1+ maps, and noise in experiments. Training 3D-CNNs on experimental data improved the prediction accuracies, but they showed limited performance. Using multi-channel-3D-CNN architecture boosted the performance of local SAR predictions with very high accuracy (>94% FSIM) and low errors (<0.4% MSE) in clinical settings. MRI channel in the model allows for the utilization of anatomy information and B1+ helps to predict SAR levels. In addition to MSE and SSIM, we utilized a rarely used metric, FSIM, and observed that FSIM provided more robust values due to higher no-data regions in head MRIs.Conclusion

Multi-channel-CNN based deep learning algorithms provide promising local SAR prediction scores in clinical settings and may open a pathway for on-the-fly local-SAR monitoring in UHF MRI scanners equipped with pTx systems.Acknowledgements

The authors are also grateful to Katherin Martin for the support during subject scanning.References

interference with, without, and despite dielectric resonance. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;21(2):192-196. doi:10.1002/jmri.202452. Collins CM, Wang Z. Calculation of radiofrequency electromagnetic fields and their effects in MRI of human subjects. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(5):1470-1482. doi:10.1002/mrm.22845

3. Deniz CM. Parallel Transmission for Ultrahigh Field MRI. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;28(3):159-171. doi:10.1097/RMR.0000000000000204

4. Meliadò EF, Raaijmakers AJE, Sbrizzi A, et al. A deep learning method for image-based subject-specific local SAR assessment. Magn Reson Med. 2020;83(2):695-711. doi:10.1002/mrm.27948

5. Gokyar S, Robb FJL, Kainz W, Chaudhari A, Winkler SA. MRSaiFE: An AI-based Approach Towards the Real-Time Prediction of Specific Absorption Rate. IEEE Access. Published online 2021:1-1. doi:10.1109/access.2021.3118290

6. Brink W, Staring M, Remis R, Webb A. Fast Subject-Specific Local SAR and B1+ Prediction for PTx at 7T using only an Initial Localizer Scan. In: Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med. 30 (2022). ISMRM; 2022:0387.

7. Milshteyn E, Guryev G, Torrado‐Carvajal A, et al. Individualized SAR calculations using computer vision‐based MR segmentation and a fast electromagnetic solver. Magn Reson Med. 2021;85(1):429-443. doi:10.1002/mrm.28398

8. Sim4Life by ZMT. Published November 2, 2022. Accessed November 5, 2022. https://zmt.swiss/sim4life/

9. Gosselin MC, Neufeld E, Moser H, et al. Development of a new generation of high-resolution anatomical models for medical device evaluation: the Virtual Population 3.0. Phys Med Biol. 2014;59(18):5287-5303. doi:10.1088/0031-9155/59/18/5287

10. Zhang L, Zhang L, Mou X, Zhang D. FSIM: A Feature Similarity Index for Image Quality Assessment. IEEE Trans Image Process. 2011;20(8):2378-2386. doi:10.1109/TIP.2011.2109730

Figures

Figure 1. UHF MRI offers high resolution anatomical imaging with clear delineation of tissue boundaries (top row). However local SAR related heating is a limiting factor, despite achieving reasonable B1+ uniformities even with pTx systems (bottom row). We propose to utilize a multichannel 3D convolutional neural network, where 3D MRIs and B1+ maps used as separate channels of the CNN, to improve the prediction accuracy of local SAR maps.

Figure 2. Generation of head/neck body models for simulations. Anatomical MRIs with 1 mm isotropic resolution were segmented by using SPM12 and ROAST toolboxes. White matter, gray matter, and cerebrospinal fluid masks were imported to iSEG toolbox of Sim4Life directly. Other tissues, (eyes, air, dura, cartilage, blood, and bone) segmented manually. Finally, soft tissue is segmented for muscle, skin, and fat manually. Segmented tissue labels were converted to volumetric objects in Sim4Life and an 8 Ch pTx coil is used for electromagnetic simulations to generate local SAR maps.

Figure 3. Electromagnetic simulations and ground truth generation: computed head/neck body models were simulated in Sim4Life by using 8-ch driven head coils to generate the experimental B1+ map distribution. For 161 randomly generate experimental B1+ shim settings (and corresponding MRIs), we optimized channel weights in simulations to generate their corresponding local SAR maps. These SAR maps were used as the ground truths for the supervised learning approach used in this work.

Figure 4. Performance comparison of different prediction approaches for experimental data. Random slices for subject-1 and -6 are given on the left right, respectively. B1+ based methods offered good feature similarities (FSIM) but showed higher overestimation errors. MRI-based predictions underestimated the peak local SAR values, since these images are not correlated to SAR directly. On the other hand, the multichannel approach predicted highest image similarities and lowest overestimation errors for the slices, validating the power of the approach on experimental data.

Figure 5. Performances of different approaches on the prediction of 10g averaged peak-spatial SAR. B1+ based method shows 8.9% overestimation, 71% goodness of fit, and 18.6% RMSE. MRI based method has 11.8% overestimation, 56% goodness of fit, and 21.2% RMSE. Multichannel approach has 11.7% overestimation, 81.4% goodness of fit, and 16.5% RMSE. Multichannel approach shows the better reliability (81.4% goodness of the fit) with reasonable overestimation error (i.e., 11.8%).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2694