2691

Local and Whole-Body SAR in UHF Body Imaging: Implications for Matrix Compression

Thomas M. Fiedler1, Mark E. Ladd1, and Stephan Orzada1

1German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany

1German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Safety, RF Arrays & Systems

RF safety of multi-channel transmit arrays is supervised with a set of matrices representing local SAR or whole-body SAR. As transmit arrays for body imaging have characteristics of both volume and local transmit coils, this study evaluates both SAR aspects: local and whole-body SAR. In all evaluated cases, the local SAR limit was reached before the whole-body SAR. Nevertheless, the whole-body SAR matrix can be used to reduce the number of local SAR matrices, reducing memory and computing time.Target audience:

Researchers involved in RF safety and high-field MRI.Introduction:

The IEC defines limits in the normal operating mode for local transmit coils (local or ‘10 g-averaged’ SAR, 10 W/kg) and for volume transmit coils (whole-body SAR, 2 W/kg).1In multi-channel RF transmit arrays, SAR depends on the time-dependent amplitude and phase of the RF shim vector u. With a pre-calculated set of normalized matrices M, representing the electric field contribution and dielectric tissue properties, SAR can be calculated using the quadratic form: SAR = u’ * Mi * u, ꓯi. Typically, a SAR matrix for each 10 g-volume in the body is computed, resulting in a set of several million local SAR matrices for a whole-body model that are compressed with a predefined overestimation to a set of several hundred virtual observation points (VOPs).2 Whole-body SAR can be expressed with a single matrix.

This study evaluates local and whole-body SAR in various antenna arrays for body imaging at 7 T MRI. Such arrays have characteristics of both volume and local transmit coils, and it is common that both SAR aspects are considered during safety monitoring.

Methods:

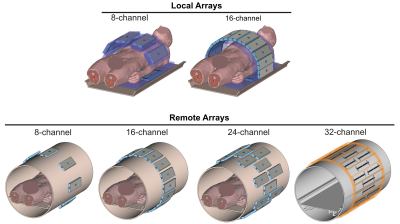

Six antenna arrays were evaluated in this study (Fig. 1)3,4 with a male body model placed with the liver region in the center. All configurations were simulated with the arms placed left and right of the body, but one array was also simulated with the arms above the head. Note that the 32-channel design is considered as a full prototype design, while the other configurations are considered as idealized simulation models without additional loses in the transmit path (e.g. cables, T/R-switches).The local SAR matrices (SARL,i) and the whole-body SAR matrix (SARG) were exported, and SAR was calculated with random shims. Worst-case SAR (SARwc) was determined by the maximum eigenvalue of all SAR matrices in the body for an eigenvector of unit voltage (||U||=1). A reduced set of local SAR matrices was determined in which all local SAR matrices dominated by the whole-body SAR matrix were removed (SARL,i - SARG is positive semidefinite).2

Results and discussion:

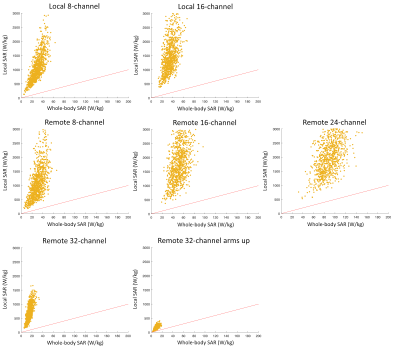

Fig. 2 shows the local vs. whole-body SAR distribution for 1000 random shims. In all cases, the local SAR limit was reached before the whole-body limit; local SAR was found to be at least approx. 1.93x higher than whole-body SAR for cases with the arms at the body sides (Table 1). The configuration with the arms above the head and thus outside the field-of-view of the RF antenna shows a smaller deviation between local and whole-body SAR.A reduction in the number of local SAR matrices of 66.7% was found for the local 8-channel configuration (from 6,185,379 to 2,143,291 matrices), with the reduction decreasing for arrays with higher channel count. Thus, consideration of the whole-body SAR matrix during the SAR matrix export can save hard disk memory and enable VOP compression on a workstation with less computing memory. Furthermore, the time to sort the SAR matrices during the compression2 is reduced (e.g. from 7 min to 4 min for the 8-channel array, from 51 min to 43 min for the 24-channel array).

Conclusion:

The results indicate that all considered RF transmit arrays are constrained by local SAR. However, the consideration of the whole-body SAR matrix can reduce the number of local SAR matrices, thus reducing the computational cost and hardware requirements for VOP compressions.Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013) / ERC Grant Agreement n. 291903 MRexcite.References

1. IEC 60601-2-33 Medical electrical equipment, Ed. 3.2 (2015)

2. Eichfelder and Gebhardt, MRM 66:1468-1476 (2011)

3. Fiedler et al., NMR in Biomed., e4515 (2021)

4. Fiedler et al., NMR in Biomed., e4656 (2021)

Figures

Fig. 1:

Configurations of local (8-channel, 16-channel) and remote (8-channel,

16-channel, 24-channel, 32-channel) antenna arrays consisting of 25 cm-long

meander micro-stripline antennas. The remote arrays

are placed outside the bore liner of the MR patient tunnel. The 24- and 32-channel

arrays consist of three interleaved rings with a 55 cm-FOV.

Fig. 2:

Maximum local vs. whole-body SAR for 1000 random shims. The red line indicates

operating points where the IEC local and whole-body SAR constraints are equally

restrictive; local SAR is more restrictive above this line. In all cases, the local

SAR limit is reached before the whole-body SAR limit.

Table 1:

Reduction in the number of local SAR matrices, worst-case (wc) local and

whole-body SAR for an eigenvector of unit voltage, and minimum overestimation

of local SAR (local SAR/whole-body SAR).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2691