2683

Graph theory-based analysis of brain diffusion data reveals network alterations in World Trade Center first responders with chronic PTSD1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Stony Brook Medicine, Stony Brook, NY, United States, 3Program in Public Health and Department of Family, Population, and Preventative Medicine, Stony Brook Medicine, Stony Brook, NY, United States, 4Environmental Medicine and Public Health, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, NY, United States, 5Department of Psychiatry, Stony Brook Medicine, Stony Brook, NY, United States, 6Environmental Health Sciences, School of Public Health, Florida International University, Miami, FL, United States, 7Occupational Medicine, Department of Medical and Surgical Specialties, Radiological Sciences and Public Health, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy, 8Department of Medicine, Stony Brook Medicine, Stony Brook, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Psychiatric Disorders

Many World Trade Center (WTC) responders continue to suffer from chronic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Multimodal imaging techniques have shown potential as putative markers for PTSD but still lie in the developmental stages. Network connectivity techniques are showing promise for investigating neuropathology influencing PTSD symptom maintenance and course. This work utilizes a graph theory approach with brain diffusion images to probe the network alterations in WTC responders with PTSD. We identified a significant difference in Characteristic Path Length (CPL) between responders with and without chronic PTSD.Introduction

World trade center (WTC) first responders worked through tremendous physical and psychological challenges in the clean-up efforts of the 9/11 terrorist attack1. Following these events, there is evidence showing that as many as 23% of rescue and recovery workers continue to suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)2. Graph theory-based analysis has previously been implemented to study functional connectivity on the group level. More recent studies utilized graph theory techniques to study brain diffusion data3,4 to investigate neurodegenerative diseases5 and neurological disorders6-8. Recently, an exciting but small study (n=47) of PTSD in a pediatric population revealed that PTSD was associated with CPL and global efficiency6-8. However, that study focused on acute PTSD status among children aged10-16 in China following exposure to a natural disaster, making the generalizability of study results unclear to other populations such as first-responders suffering from chronic PTSD twenty years after surviving a terrorist attack. In addition, since PTSD is known to cause cognitive impairment and accompanying neurodegeneration, the applicability of results to a study where cognitive status was controlled by design was also unclear. The present work explores the use of graph theory techniques with diffusion data to determine if brain networks are altered in WTC responders with chronic PTSD compared to their counterparts without PTSD and healthy controls.Methods

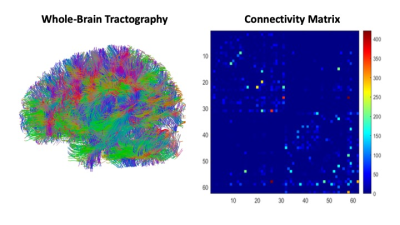

Diffusion data were acquired from 101 volunteers on a 3T scanner (Siemens Biograph mMR). Within this dataset, 91 were WTC responders (43 chronic PTSD as diagnosed through Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV, and 10 subjects were non-responder healthy controls). Diffusion images were acquired using single shell diffusion-weighted EPI acquisitions (TE/TR = 87.6/4680 ms, b value = 1200, 64 diffusion directions, in-plane resolution = 2 mm, slice thickness = 2 mm, matrix size = 128 x 128, multiband factor = 2). Connectivity matrices were generated via deterministic tractography analysis using QSDR reconstruction with DSI-Studio and consisted of 62 regions of interest (ROI, which are the nodes of the network) using the DKT atlas with whole-brain seeding using 100,000 seeds. The weight of the edge connecting two nodes was defined as 1 over the number of tracts connecting the respective ROIs. Network measures for each subject were calculated using the Brain Connectivity Toolbox software for MATLAB9, and analyzed via two-sample t-tests. Two commonly used thresholds for CPL (weighted and binary), Global Efficiency were calculated4.Results

Figure 1 shows the tractography results and the connectivity matrix for a representative subject while Figure 2 depicts comparisons of network analysis for healthy controls, PTSD-, and PTSD+ subjects. Significant differences were found in CPL (weighted) and (binary) between PTSD+ and PTSD- subjects (p= 0.003 and p= 0.02, respectively; the former survives multiple comparison correction). Additionally, PTSD+ subjects were found to have increased CPL relative to healthy controls (p= 0.0008, survived multiple comparison correction) and the total number of connections in PTSD+ subjects were significantly lower than PTSD- responders (p= 0.048). Of note, all nine subjects with the highest weighted CPL>80 were PTSD+. There was no statistically significant differences when measuring global efficiency.Discussion

In the largest study to date to examine the relationship between chronic PTSD and the topography of neural connections, we found that weighted and binary CPL differed between the PTSD+ and PTSD- groups and also identified a significant increase in CPL for PTSD+ subjects relative to healthy controls. Our findings are consistent with previous investigations on CPL and PTSD status, where CPL was found to be increased in pediatric patients with PTSD8. An increase in CPL for PTSD subjects could imply that the brain’s level and efficiency of communication has diminished as a result of chronic PTSD10, but could also signify a vulnerability marker for the development of PTSD following traumatic exposure. Since CPL represents the average shortest path length between different brain regions, an increase could imply that paths may be broken. When considering the total number of edges between brain regions in PTSD+ and PTSD- subjects, we also see a significant decrease in the PTSD+ subjects seen in Figure 2(C), although the p-value of this finding is barely below 0.05 and will not survive multiple comparison correction. This reduction of tracts is expected to be related to the increase in CPL.Conclusion

PTSD+ WTC responders had increased CPL relative to their PTSD- counterparts and healthy controls, suggesting that network connectivity of the brain may be linked to chronic PTSD. Further work is necessary to determine if weighted CPL sustains symptomatology in chronic PTSD or if it also facilitates the emergence of PTSD symptomatology.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the generous funding of the following institutions: (NIH/NIA R01 AG049953), (CDC/NIOSH U01 OH011314), (NIH/NIA P50 AG005138), and (NIH/NIA R01 AG049953).

We would also like to acknowledge ongoing funding to monitor World Trade Center responders (CDC 200-2011-39361)

References

1. Liu, B., Tarigan, L. H., Bromet, E. J. & Kim, H. World Trade Center disaster exposure-related probable posttraumatic stress disorder among responders and civilians: a meta-analysis. PloS one 9, e101491 (2014).

2. Clouston, S. A. et al. Cognitive impairment and World Trade Centre-related exposures. Nature Reviews Neurology, 1-14 (2021).

3. Hallett, M. et al. Human brain connectivity: Clinical applications for clinical neurophysiology. Clinical Neurophysiology 131, 1621-1651 (2020).

4. Nigro, S. et al. The Role of Graph Theory in Evaluating Brain Network Alterations in Frontotemporal Dementia. Frontiers in Neurology 13 (2022).

5. Barbagallo, G. et al. Structural connectivity differences in motor network between tremor‐dominant and nontremor Parkinson's disease. Human brain mapping 38, 4716-4729 (2017).

6. Long, Z. et al. Altered brain structural connectivity in post-traumatic stress disorder: a diffusion tensor imaging tractography study. J Affect Disord 150, 798-806 (2013).

7. Suo, X. et al. Large‐scale white matter network reorganization in posttraumatic stress disorder. Human brain mapping 40, 4801-4812 (2019).

8. Suo, X. et al. Anatomic insights into disrupted small-world networks in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder. Radiology 282, 826-834 (2017).

9. Rubinov, M. & Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 52, 1059-1069 (2010).

10. Onoda, K. & Yamaguchi, S. Small-worldness and modularity of the resting-state functional brain network decrease with aging. Neuroscience letters 556, 104-108 (2013).