2670

Whole Brain Multivoxel Pattern Analysis of resting fMRI in Autism and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder1Department of Psychology & The Center for Innovative Research in Autism., University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, United States, 2University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, United States, 3Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Atlanta, GA, United States, 4Carle Illinois Advanced Imaging Center, Urbana, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, Brain Connectivity, Multivoxel Pattern Analysis

This study examined whole-brain resting state fMRI connectivity patterns in autistic and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) adults in comparison with neurotypical adults using multivoxel pattern analysis. Results highlight alterations in cerebellar-cortical functional connectivity (FC) in autistic participants and the involvement of cerebellum and inferior frontal gyrus in ADHD.Introduction

Autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are common disorders affecting youth and share a high extent of symptomatology1. Atypical functional connectivity (FC) is a hallmark feature of autism and ADHD2-4. Owing to the heterogeneous nature and widespread FC alterations seen among these disorders, it is challenging to gain a mechanistic understanding of the underlying disorder. The study aims at investigating the shared and distinct resting-state FC patterns in autism and ADHD using a data-driven whole-brain connectome wide Multivoxel pattern analysis (MVPA).Methods

15 autistic, 15 Neurotypical (NT), and 19 ADHD young adults of age group, 16-29 years participated in this fMRI study. All participants underwent MRI scanning on a Siemens MAGNETOM 3T Prisma scanner. Resting fMRI data were collected for 12 minutes, with 6 minutes of acquisition in the anterior-posterior direction and the rest in posterior-anterior direction. Data preprocessing was done in Conn Connectivity toolbox (conn20b; www.nitrc.org/projects/conn) and Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM12) software (www.fl.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). The preprocessing involved realignment, unwrapping, outlier identification, coregistration to anatomical scan, spatial normalization and smoothing. Denoising was performed by anatomical component-based noise correction procedure called aCompcor, which corrects for physiological noise by regressing out cerebral white matter and CSF along with the six head motion parameters and their first order derivatives of realignment parameters. We employed a whole-brain MVPA using Conn Connectivity toolbox5. A principal component analysis (PCA) was used for dimensionality reduction by estimating a multivoxel representation of the connectivity pattern by computing the pairwise connectivity between each voxel and rest of the voxels in the brain in a two-step process. Initially, 64 PCA components are retained at the subject level while characterizing each participant’s voxel-to-voxel structure. The second step involved PCA decomposition of the between-subjects variability in voxel-to-voxel connectivity between each voxel and the voxels from the rest of the brain. Jointly across all subjects and separately for each voxel, the three strongest components were retained. An F-test was performed (at a voxel level threshold of p<0.001, and a cluster threshold of p<0.05, corrected for family-wise error) on all these three MVPA components simultaneously to identify the voxels that show significant differences in connectivity patterns between the groups (autism & NT, and ADHD & NT).Results

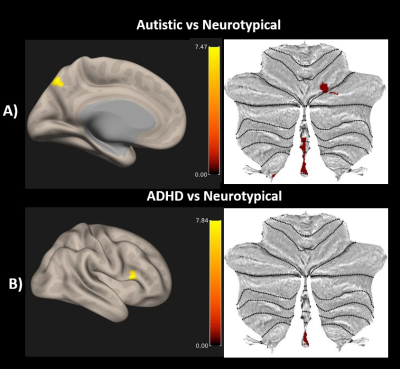

MVPA identified the right cerebellar vermis 9, left precuneus and the right cerebellum VI for autism vs NT. The right inferior frontal gyrus (RIFG) and the right cerebellar vermis 9 were identified for ADHD vs NT comparison (See Table 1 and Figure 1).| Table: 1 Peak clusters obtained from the whole brain Connectome wide MVPA | |||

| Contrast for F-test | MNI Co-ordinates | Peak Cluster | Voxels per cluster |

| Autistic vs. NT | +02 -48 -36 | Vermis 9 | 68 |

| -4 -78 +48 | Precuneus | 42 | |

| +20 -72 -22 | Cerebellum Right VI | 29 | |

| ADHD vs. NT | +52 +18 +14 | Right Inferior Frontal Gyrus | 37 |

| +02 -50 -40 | Vermis 9 | 31 | |

Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate the underlying cerebellar and precuneus (a central node in DMN) contribution to the resting FC pattern of autistic individuals and the involvement of the cerebellar vermis and the RIFG in the connectivity pattern of ADHD participants. Consistent reports on the role of the cerebellum in cognition and emotion made it a key brain region affected in autism and ADHD6, 7. A recent study provided evidence for a third somatomotor representation in the cerebellar vermis8, which makes the cerebellar vermis a noteworthy region for further research. This study elucidates the involvement of cerebellar-cortical circuitry in both these neurodevelopmental disorders. Future studies with higher field strength can help gain a better mechanistic understanding of the functional abnormalities of these disorders.Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate the shared functional connectivity profile of the cerebellum with key cortical areas in autism and ADHD and further underscores the need for revisiting the role of the cerebellum in neurodevelopmental disorders.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Benjamin McManus, Gabriela Sherrod, Rishi Deshpande, and Austin Svancara for their help at different stages of data collection. This research was supported by the Civitan International Pilot Research grant at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.References

1. Matson JL, Rieske RD, Williams LW. The relationship between autism spectrum disorders and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an overview. Res Dev Disabil. 2013; (34): 2475–2484.

2. Kana RK, Uddin LQ, Kenet T, Chugani D, Müller RA. Brain connectivity in autism. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;(8):349.

3. Bednarz HM, Kana RK. Patterns of Cerebellar Connectivity with Intrinsic Connectivity Networks in Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;(49), 4498–4514.

4. Uddin LQ, Dajani DR, Voorhies W, Bednarz H, Kana RK. Progress and roadblocks in the search for brain-based biomarkers of autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7(8):e1218.

5. Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Nieto-Castanon A. Conn : A Functional Connectivity Toolbox for Correlated and Anticorrelated Brain Networks. Brain Connectivity. 2012;2(3):125–41.

6. Muriel MK. Bruchhage, Maria-Pia Bucci, Esther BE. Becker, Cerebellar involvement in autism and ADHD. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Elsevier. 2018;(155):61-72.

7. Stoodley CJ. The Cerebellum and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Cerebellum. 2016;15(1):34-37.

8. Saadon-Grosman N, Angeli PA, DiNicola LM, Buckner RL. A third somatomotor representation in the human cerebellum. J Neurophysiol. 2022;128(4):1051-1073.