2665

Improved DCE-MRI analyses of blood-brain barrier integrity in subjective memory and mild cognitive impairment: New results from the CANN trial1Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom, 2University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom, 3University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 4Department of Radiology, C.J. Gorter Centre for High Field MRI, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Permeability, DCE-MRI, Low-level Blood-brain-barrier Leakage, Mild cognitive impairment

We implemented recent developments in DCE-MRI pre-processing and analysis techniques to compare local differences in blood brain barrier (BBB) integrity in subjective memory impairment (SMI) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), two early indicators of Alzheimer’s disease. Also, as part of the CANN trial, we explored the impact of a combined flavanol and omega-3 fatty acid-based nutritional intervention on BBB leakage. The results show that BBB leakage in memory processing regions can distinguish between SMI and MCI, and thus can be used to quantitatively assess the progress of cSVD towards onset of MCI and/or early indication of Alzheimer’s disease.Introduction

The pathophysiology of cerebral small vessel diseases (cSVD) is directly related to integrity of the aging blood brain barrier (BBB). The relative risk of cSVD can be decreased through individual dietary interventions like fish-derived fatty acids and plant bioactives1. The effect of a combined dietary intervention on BBB leakage was investigated in the Cognitive Ageing, Nutrition and Neurogenesis (CANN) randomised controlled trial, using an omega-3 fatty acid flavonoid (OM3FLAV) supplement1. Dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE)-MRI provides quantitative measurement of BBB leakage and thus facilitates diagnosis, as well as progression and treatment monitoring of cSVDs, Alzheimer’s, and dementia2. However, capturing subtle leakage, or change in it due to a nutrition intervention, and mitigating systematic errors in estimation demand multiple modifications to conventional DCE-MRI analysis. In this study, we incorporated recent developments in DCE-MRI analysis that provide more accurate and precise leakage measurements2 to compare the low-level BBB leakage in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to subjective memory impairment (SMI)3─a self-diagnosed pre-MCI cognitive state. We also quantify the change in BBB leakage for SMI cohort after year-long oral intake of OM3FLAV1.Methods

The cohort size, demographics, and the acquisition protocol were same as our previously presented abstract4. Briefly, nine out of 17 SMI subjects consumed the OM3FLAV ─cocoa flavanol-containing chocolate drops along with fatty-acid containing fish oil capsules orally, each day, for a year. Eight SMI and five out of seven MCI participants received the placebo─flavanol-poor chocolate drops and omega-3-free oil capsules.All participants were scanned at 12 months using a 3T scanner (Discovery 750w; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with a 12-channel head coil. The protocol included: 3D T1-weighted inversion-recovery (IR) prepared-fast spoiled gradient recalled echo (FSPGR); DESPOT1-HIFI experiment consisting of SPGR acquisitions with 5, 10, and 15° flip angles (FAs) along with a 5°-FA IR-SPGR; and lastly, a 10.5-minute-15°-FA multi-phase SPGR (TR/TE=6.3/2.4 ms) sequence after Gadovist® injection (dose: 0.1mmol/kg body weight, rate: 1ml/s). Additionally, for scanner drift assessment, seven age-and-BMI-matched subjects underwent a sham, non-contrast version of the protocol.

Brain extraction and motion correction of DCE-MRI data was performed using BET and MCFLIRT in FSL5,6. The structural T1-weighted images and motion-corrected DCE-MRI data were aligned to 15°-SPGR images using rigid-body registration (FSL-FLIRT5,7). Finally, we used FastSurfer (a deep-learning-based version of FreeSurfer)8 to segment the structural data into two larger brain regions: WM, GM, and three smaller regions typically involved in memory processing and storage—the hippocampus, thalamus, and amygdala.

Further analysis was performed in Python (version 3.9.19) using code developed for improved DCE-MRI analyses (https://github.com/mjt320/SEPAL). The median scanner drift was found to be negligible for all ROIs and therefore was not incorporated in subsequent analysis. Median signal enhancement for each ROI was converted to dynamic concentration estimates10. Region-wise pre-contrast T1 values were calculated from DESPOT-HIFI data, which incorporated correction for B1-inhomogeneities and fitting for the apparent longitudinal relaxation time.11For pharmacokinetic modelling, we used the Patlak model12. To model longitudinal relaxation in the fast water exchange limit and to decrease the sensitivity of leakage to blood flow, the first-pass and early-post-injection data-points were excluded from dynamic concentration estimates2. Finally, fitting provided two parameters: the permeability surface area product (PS), which reflects BBB leakage and vp, which refers to the blood plasma volume fraction13. For each subject, the vascular input function was measured manually from a voxel placed in the superior sagittal sinus.

Results

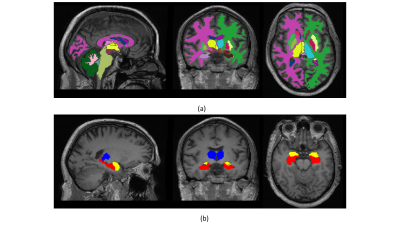

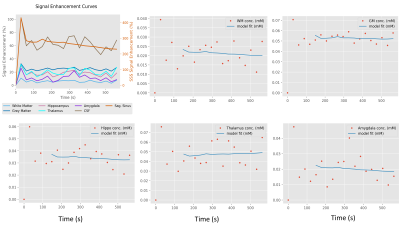

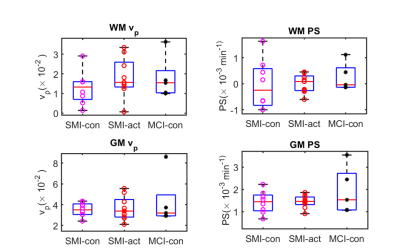

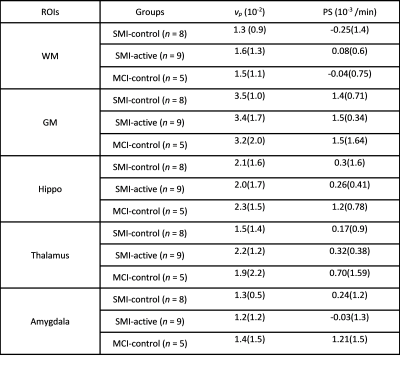

Figure 1(a) shows an example of a segmentation on T1-weighted structural data with 1(b) masks for regions involved in memory: namely, the hippocampus, thalamus, and amygdala for a 56-year-old female SMI participant. Figure 2 demonstrates Patlak fits to the median concentration data obtained from each ROI for that same subject. Figure 3(a-b) shows boxplots of DCE-MRI parameters for SMI-control, SMI-active, and MCI-control groups. For the hippocampus and amygdala, leakage in MCI subjects was significantly higher than in SMI-control and SMI-active groups (p=0.045 and 0.042, respectively; same p-value for group-wise comparisons in both hippocampus and amygdala).Table 1 summarises the median and inter-quartile range of DCE-MRI parameters.Discussion

We used recently recommended DCE-MRI analysis developments2 to investigate local differences in BBB integrity in approximately age- and body-mass-index(BMI)-matched SMI and MCI groups. For larger ROIs like WM and GM, BBB permeability was similar for the three groups. However, for regions specifically involved in memory storage and processing, like the hippocampus and amygdala, the MCI group had higher leakage (lower integrity) than both SMI groups.No significant differences were seen with the dietary intervention. The small sample size of this exploratory study may have limited our sensitivity to changes. In future extensions of this study, we aim to increase the sample size to improve our statistical power. Also, the duration of DCE acquisition will be increased to better quantify low PS values.

Conclusion

In this exploratory study, we incorporated recent advancements in subtle BBB leakage analysis to compare permeability metrics for SMI and MCI cohorts. Additionally, we explored the potential impact of a nutritional intervention on SMI participants. Results show that in memory processing regions, MCI participants have a higher leakage than SMI cohorts, suggesting potential for leakage parameters in characterising the onset of MCI. A larger sample may be needed to observe any possible effect of the intervention.Acknowledgements

I acknowledge the helps from our IT team member, specially Dr. Jacob Newman, for his continuous help towards running the FastSurfer in the high performance cluster.References

1. Irvine MA, Scholey A, King R, et al. The Cognitive Ageing, Nutrition and Neurogenesis (CANN) trial: Design and progress. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2018;4(1):591-601.

2. Manning C, Stringer M, Dickie B, et al. Sources of systematic error in DCE-MRI estimation of low-level blood-brain barrier leakage. Magnetic resonance in medicine. 2021.

3. Jessen F, Wiese B, Bachmann C, et al. Prediction of dementia by subjective memory impairment: effects of severity and temporal association with cognitive impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):414-422.

4. R. S, D.R. W, R. G, et al. DCE-MRI of blood brain barrier leakage in subjective memory and mild cognitive impairment: The Cognitive Ageing, Nutrition & Neurogenesis Trial 2022 Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB & ISMRT 31st Annual Meeting; 2022; London, UK.

5. Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage. 2002;17(2):825-841.

6. Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17(3):143-155.

7. Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143-156.

8. Henschel L, Conjeti S, Estrada S, Diers K, Fischl B, Reuter M. FastSurfer - A fast and accurate deep learning based neuroimaging pipeline. NeuroImage. 2020;219:117012.

9. Rossum GV, Drake FL. Python 3 Reference Manual. CreateSpace; 2009.

10. Armitage PA, Farrall AJ, Carpenter TK, Doubal FN, Wardlaw JM. Use of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI to measure subtle blood–brain barrier abnormalities. Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2011;29(3):305-314.

11. Deichmann R, Haase A. Quantification of T1 values by SNAPSHOT-FLASH NMR imaging. Journal of Magnetic Resonance (1969). 1992;96(3):608-612.

12. Patlak CS, Blasberg RG, Fenstermacher JD. Graphical evaluation of blood-to-brain transfer constants from multiple-time uptake data. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 1983;3(1):1-7.

13. Heye AK, Thrippleton MJ, Armitage PA, et al. Tracer kinetic modelling for DCE-MRI quantification of subtle blood-brain barrier permeability. NeuroImage. 2016;125:446-455.

Figures

Figure 1: (a) FastSurfer Segmentation result for a 56-year-old subjective memory impairment (SMI) participant taking placebo. (b) Hippocampus (red), amygdala (yellow), and thalamus (blue) ROI masks for the same subject

Figure 2: Signal enhancement curves for different region of interests (ROIs), together with Patlak model fits for each concentration time curve of the analysed ROIs for 56-year-old female subjective memory impairment (SMI) participant.

Table 1: Median (Inter-quartile range) of fractional plasma volume (vp) and permeability-surface area product (PS) for WM, GM, Hippocampus, Thalamus, and Amygdala, as obtained after 12 months of intervention. Abbreviations: SMI, subjective memory impairment; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; WM, white matter; GM, grey matter. Group abbreviations: SMI-control, SMI with omega-3- and flavanol-poor intervention; SMI-active, SMI with nutritional (OM3FLAV) intervention; MCI-control, MCI with omega-3- and flavanol-poor intervention; ROI, region of interest.