2661

Iron deficiency anemia is associated with abnormal cerebral metabolic rate, blood brain barrier permeability and cognitive function.1Pediatrics, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles-USC KSOM, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 3Neuropsychology, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles-USC KSOM, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 4Transfusion Medicine, Children's Hospital of Los Angeles-USC KSOM, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 5Transfusion Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 6Transfusion Medicine, Cedar Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 7Transfusion Medicine, City of Hope Medical Center, Duarte, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Dementia, Metabolism, Iron Deficiency

Iron deficiency is the predominant cause of anemia in adults, typically occurring in women with heavy menses, endometriosis or fibroids. We study cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2), blood brain barrier (BBB) permeability to water, and neurocognitive function in 34 women with iron deficiency anemia (IDA). We observed striking deficits in verbal and spatial memory, perceptual reasoning, and crystalized intelligence that were strongly correlated with hemoglobin level. CMRO2 was lower than predicted by anemia alone, correlated to BBB permeability to water, and associated with poorer neurocognitive performance, suggesting decreased brain capillary surface area for oxygen and water diffusion.Introduction

In the United States alone, 5.6% (~19 million people) of the population is anemic1, with 1.5% (~5 million) having moderate anemia (hemoglobin level < 11 g/dl). Iron deficiency is the predominant cause of anemia in adults and is overrepresented in minority and financially disadvantaged populations1. Iron is essential for cerebral function, particularly in metabolically active areas such as the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and prefrontal cortex2. Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) in infancy and childhood is well known to cause permanent damage to grey and white matter structure3-6 and function5,6. In contrast, adult-onset IDA is often perceived to be benign, easily recognized, readily treated, and completely reversible. However, there is a shocking lack of supporting data for this perception. We evaluated neurocognitive function and neurovascular integrity in 34 adult women with IDA to provide estimates of effect size for a potential interventional trial.Methods

We recruited potential blood donors at four donor centers in the Los Angeles basin (Childrens Hospital Los Angeles, University of California Los Angeles, Cedars Sinai Medical Center, and City of Hope Medical Center) whose screening hemoglobin was less than 10.5 g/dl. We also recruited using social media resources provided by the Clinical Translational Science Institute at USC and by Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; all women recruited in this manner underwent a separate hemoglobin screening visit. Exclusion criteria included systemic conditions associated with anemia or with small vessel disease. Iron deficiency anemia was confirmed by complete blood count with smear, reticulocyte count, iron indices, methyl malonic acid, hemoglobin electrophoresis, and high-sensitivity C reactive protein measurements. Patients underwent a comprehensive neuropsychiatric evaluation including subtests of the Weschler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI-II), the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), the Rey Complex Figure Test (RCFT), and the NIH Cognitive Toolkit. MRI examination was performed on a Philips 3T Achieva with 32 element head coil and digital receiver chain. Cerebral blood flow was measured by phase contrast of the cerebral and vertebral arteries as previously described7. Sagittal sinus oximetry as assessed using T2 Relaxation Under Spin Tagging(TRUST) using standard techniques8 and a human blood calibration curve appropriate for anemic subjects9. Blood brain barrier permeability to water was measured using Water Extraction by Phase Contrast Arterial Spin Tagging (WEPCAST) using a sequence developed by Dr. Hanzhang Lu and colleagues10. This technique uses psuedocontinuous arterial spin labeling at an imaging plane 83 mm below the anterior-posterior cingulate line and measures the fraction of labelled spins entering the sagittal sinus (normalized to a M0 image). The labelling duration was four seconds, label delay three seconds, and phase contrast encoding direction was foot-head.Results

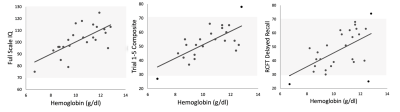

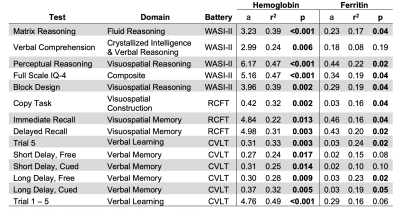

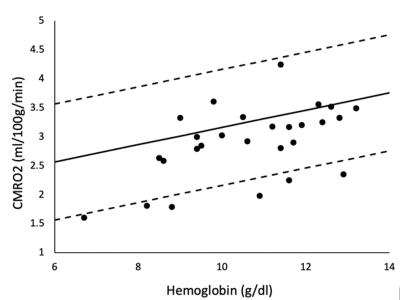

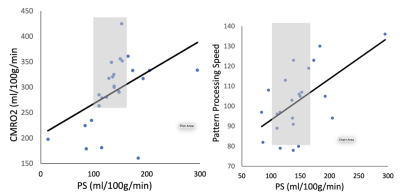

Our subjects demonstrate a clean IDA phenotype with low ferritin and transferrin saturation, high iron binding capacity, decreased MCV and MCHC, and hypochromia on blood smear (not shown). Neurocognitive function was impaired proportional to anemia severity. Figure 1 demonstrates a linear relationship between three neurocognitive scores and hemoglobin values. Figure 2 is a table summarizing the complete comparison of detectable effect sizes across more cognitive domains. IDA was also associated with decreased metabolic rate and derangements in BBB water permeability. Figure 3 demonstrates CMRO2 versus hemoglobin; the 95% confidence intervals represent data from all-cause chronic anemia syndromes11. While historical controls describe much of the behavior, the residual differences from this relationship were highly correlated with hypoalbuminemia, lymphocyte count, and ferritin, three markers of functional iron sufficiency. Figure 4 demonstrates that the BBB permeability-surface area product (PS) to water predicts CMRO2 (r2 = 0.21, p=0.019) and pattern processing speed (r2 = 0.38, p=0.00024) from the NIH Cognitive toolkit. Anemic subjects exhibited both increased and decreased PS relative to historical controls. However, decreased PS was pathological, associated with poor cognitive performance and decreased CMRO2.Discussion

Our present data refute the hypothesis that moderate IDA is “benign”, with subjects operating more than one standard deviation below their cognitive potential, with unknown academic and professional consequences. Given the over-representation1 of moderate IDA in young and middle-aged black (10.2%) and Hispanic (5.2%) women, compared with non-Hispanic white women (1.5%), failure to adequately diagnose and treat IDA is socially unjust. Mechanistically, we demonstrate that IDA suppresses CMRO2 far out of proportion to the impact of anemia, itself. Oxygen extraction is normal in these subjects, so the decrease in CMRO2 represents a failure of compensatory hyperemia. Models of cerebral oxygen exchange suggest that decreased CMRO2 can be explained by the loss of functional capillary surface area12, linking associations between CMRO2 and PS measurements. Since iron is essential for oxygen sensing in brain capillaries, we postulate that iron deficiency is impairing oxygen-supply demand matching in the brain, blunting compensatory hyperemia, and disproportionately lowering CMRO2 and PS in vulnerable subjects.Conclusion

Moderate IDA is common in adult women and has profound neurocognitive and neurovascular consequences, including impairment of CMRO2 and BBB water permeability-surface area product. Further work will define the regional brain derangements in flow, oxygen extraction and functional connectivity as well as determine the reversibility of these deficits to iron replacement.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Saban Research Institute 2nd ROI Pilot Grant, the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (1RO1HL136484-A1), the National Center for Research Resources (UL1 TR001855-04) and by Research Support-in-Kind from Philips Healthcare.References

1. Le CH. The Prevalence of Anemia and Moderate-Severe Anemia in the US Population (NHANES 2003-2012). PLoS One 2016;11:e0166635.

2. Ward RJ, Zucca FA, Duyn JH, Crichton RR, Zecca L. The role of iron in brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:1045-60.

3. Raz S, Koren A, Levin C. Associations between red blood cell indices and iron status and neurocognitive function in young adults: Evidence from memory and executive function tests and event-related potentials. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2022.

4. Vlasova RM, Wang Q, Willette A, et al. Infantile Iron Deficiency Affects Brain Development in Monkeys Even After Treatment of Anemia. Front Hum Neurosci 2021;15:624107.

5. Algarin C, Karunakaran KD, Reyes S, et al. Differences on Brain Connectivity in Adulthood Are Present in Subjects with Iron Deficiency Anemia in Infancy. Front Aging Neurosci 2017;9:54.

6. Algarin C, Peirano P, Chen D, et al. Cognitive control inhibition networks in adulthood are impaired by early iron deficiency in infancy. NeuroImage Clinical 2022;35:103089.

7. Bush AM, Borzage MT, Choi S, et al. Determinants of resting cerebral blood flow in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2016;91:912-7.

8. Bush AM, Coates TD, Wood JC. Diminished cerebral oxygen extraction and metabolic rate in sickle cell disease using T2 relaxation under spin tagging MRI. Magn Reson Med 2018;80:294-303.

9. Bush A, Borzage M, Detterich J, et al. Empirical model of human blood transverse relaxation at 3 T improves MRI T2 oximetry. Magn Reson Med 2017;77:2364-71.

10. Lin Z, Li Y, Su P, et al. Non-contrast MR imaging of blood-brain barrier permeability to water. Magn Reson Med 2018;80:1507-20.

11. Vu C, Bush A, Choi S, et al. Reduced global cerebral oxygen metabolic rate in sickle cell disease and chronic anemias. Am J Hematol 2021;96:901-13.

12. Angleys H, Ostergaard L, Jespersen SN. The effects of capillary transit time heterogeneity (CTH) on brain oxygenation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015;35:806-17.

Figures