2655

Cascade of Perfusion and Brain Atrophy in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Longitudinal Study1Radiation Oncology, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, United States, 2Computer Science, State University of New York at Binghamton, Binghamton, NY, United States, 3Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 4Radiology and Neurology, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, United States, 5Psychiatry, Psychology, and Neurology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 6Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 7Radiology, New York University School of Medicine, New York City, NY, United States, 8Neurology and Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States, 9Radiology and Biomedical Engineering, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Arterial spin labelling

We conducted a longitudinal study to determine if reduced temporoparietal and frontal cerebral blood flow (CBF) in elderly population leads to reduced gray matter volumes (GMVs) in the temporal lobe, or vice versa. We observed smaller GMVs in the temporal pole (TP) region in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. We also found associations of: (1) the TP GMVs with subsequent temporoparietal CBF declines; (2) the TP CBF with its own subsequent GMV changes; and (3) the hippocampal GMVs with longitudinal frontal CBF declines. Hypoperfusion in the temporal lobe may be an early event driving atrophy, followed by temporoparietal and frontal hypoperfusion.Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has been associated with different manifestations, including diminished cerebral blood flow (CBF) (1-3) and gray matter volume (GMV) (4-6). The most consistent findings in the literature for decreased CBF and metabolism of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD are in the temporoparietal region at the early stage and spread to the frontal region at the later stage (7-9). However, gray matter atrophy in the medial temporal lobe (MTL) (10-12), including the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex, was predominantly reported. Dissociated regional patterns of CBF and GMV have been observed in these cohorts (10,13). Indeed, it has been debated whether decreased CBF represents a pathological reduction in blood supply or a response to reduced metabolic demand. One study indicated that hippocampal atrophy occurs earlier than hypoperfusion in the temporoparietal region (14), while other studies indicated that vascular damage and reduced perfusion in the parietal association cortex lead to the initiation and progression of AD pathology in the MTL (15,16). This study took advantage of the longitudinal design of the Cardiovascular Health Study Cognition Study (CHS-CS) to elucidate the temporal relationship between temporoparietal and frontal hypoperfusion and MTL atrophy.Methods

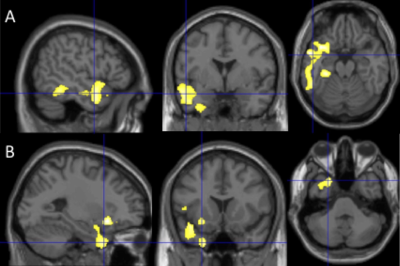

In the CHS-CS, 148 volunteers, including 58 normal controls (NC), 50 MCI, and 40 AD, had perfusion MRIs and T1-weighted structural MRIs during 2002-2003 (Time 2). Sixty-three volunteers had follow-up MRIs (Time 3). Forty of the 63 volunteers had structural MRIs during 1997-1999 (Time 1).GMV images were derived from the T1-weighted structural MRIs by using the DARTEL-based voxel-based morphometry (VBM) in SPM12. A general linear model (GLM) was performed to examine the GMV differences on a voxel-by-voxel basis between 58 NC, 50 MCI and 40 AD subjects (Time 2) by considering age, gender, and total intracranial volume (TIV) as confounding variables. The corrected cluster-level p values were set to p < 0.05. The clusters with significant GMV differences between the NC and AD groups were considered as GMV regions of interest (ROIs). Because of frequently reported GMV loss in hippocampus (10-12), hippocampal ROIs were added as exploratory GMV ROIs. Two perfusion ROIs, the temporoparietal region and superior medial prefrontal region, were extracted from the clusters with perfusion deficits in AD from our prior cross-sectional study (17).

Multiple linear regression models were used to investigate whether the baseline regional GMVs (Time 1 or Time 2) were related to longitudinal regional perfusion changes (from Time 2 to Time 3) and the baseline regional CBF values (Time 2) were related to longitudinal regional GMV changes (from Time 2 to Time 3).

Results

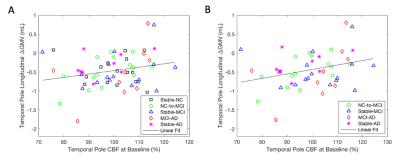

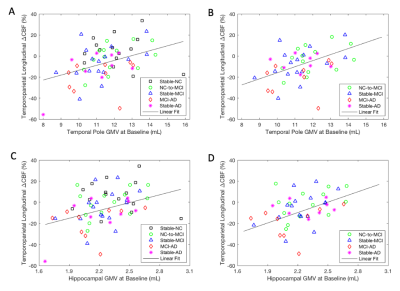

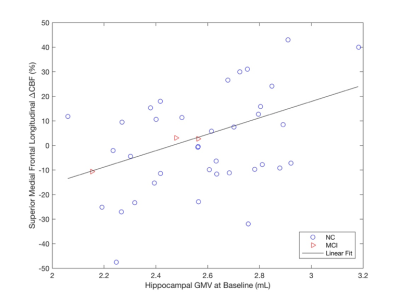

At Time 2, we observed smaller GMVs (p < 0.05) in the temporal pole (TP) region in AD compared to NC and MCI (Fig. 1). We also found association of: (1) the TP CBF at Time 2 with its own subsequent GMV changes for all the subjects (Fig. 2A, p = 0.079) and the subjects with AD progression (all the subjects excluding those in the stable NC group) (Fig. 2B, p = 0.048); (2) the TP GMVs at Time 2 with subsequent temporoparietal CBF declines for all the subjects (Fig. 3A, p = 0.0089) and the subjects with AD progression (Fig. 3B, p = 0.0032); the hippocampal GMVs at Time 2 with subsequent temporoparietal CBF declines from Time 2 to Time 3 for all of the subjects (Fig. 3C, p = 0.027) and for the subjects with AD progression (Fig. 3D, p = 0.012); and (3) the left hippocampal GMVs at Time 1 with subsequent superior medial frontal CBF declines (Fig. 4, p = 0.0343) from Time 2 to Time 3.Discussion

The observed temporal pole region is different from frequently reported early AD atrophic regions, or hippocampal and entorhinal areas (18-21). By contrast, using the 1997-1999 CHS-CS cohort, we observed significant hippocampal atrophy in AD in a prior publication (22). We postulated that the observed atrophy in the temporal pole region reflects brain structural atrophy in a more advanced stage of AD compared to our prior 1997-1999 cohort.We found that baseline atrophy in the left temporal pole and left hippocampal regions was correlated with subsequent perfusion decline in the temporoparietal region, suggesting that GMV in the temporal lobe is a strong indicator of future perfusion decline in the adjacent vessel territory.

We observed that baseline hippocampal GMVs (rather than GMVs in the temporal pole region) were associated with perfusion decline in the superior medial frontal region 4-5 years later. This data directly supports that hippocampal atrophy occurs earlier than atrophy in the temporal pole region.

Longitudinal GMV changes were found to be associated with baseline brain perfusion in the temporal pole region but not in the hippocampal region. Failure to find the association between hippocampal perfusion and its atrophy may be caused by the cohort that we analyzed being in the relatively advanced stage and relative older age group as mentioned earlier.

Conclusion

Reduced CBF in the temporal lobe may be an early event driving its own atrophy, followed by temporoparietal and frontal hypoperfusion. Boosting CBF at a critical stage may be an effective strategy for slowing AD process.Acknowledgements

This research was supported by contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, HHSN268201800001C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086, 75N92021D00006, and grants U01HL080295 and U01HL130114 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional support was provided by R01AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). A full list of principal CHS investigators and institutions can be found at CHS-NHLBI.org.References

1. Chen W, Song X, Beyea S, D'Arcy R, Zhang Y, Rockwood K. Advances in perfusion magnetic resonance imaging in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(2):185-196.

2. Zhang H, Wang Y, Lyu D,et al. Cerebral blood flow in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2021;71:101450.

3. Kisler K, Nelson AR, Montagne A, Zlokovic BV. Cerebral blood flow regulation and neurovascular dysfunction in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017;18(7):419-434.

4. Barnes J, Bartlett JW, van de Pol LA,et al. A meta-analysis of hippocampal atrophy rates in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30(11):1711-1723.

5. Pini L, Pievani M, Bocchetta M,et al. Brain atrophy in Alzheimer's Disease and aging. Ageing Res Rev 2016;30:25-48.

6. Franko E, Joly O, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. Evaluating Alzheimer's disease progression using rate of regional hippocampal atrophy. PLoS One 2013;8(8):e71354.

7. Messa C, Perani D, Lucignani G,et al. High-resolution technetium-99m-HMPAO SPECT in patients with probable Alzheimer's disease: comparison with fluorine-18-FDG PET. J Nucl Med 1994;35(2):210-216.

8. Herholz K, Schopphoff H, Schmidt M,et al. Direct comparison of spatially normalized PET and SPECT scans in Alzheimer's disease. J Nucl Med 2002;43(1):21-26.

9. Dolui S, Li Z, Nasrallah IM, Detre JA, Wolk DA. Arterial spin labeling versus (18)F-FDG-PET to identify mild cognitive impairment. Neuroimage Clin 2020;25:102146.

10. Luckhaus C, Cohnen M, Fluss MO,et al. The relation of regional cerebral perfusion and atrophy in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early Alzheimer's dementia. Psychiatry Res 2010;183(1):44-51.

11. Lacalle-Aurioles M, Mateos-Perez JM, Guzman-De-Villoria JA,et al. Cerebral blood flow is an earlier indicator of perfusion abnormalities than cerebral blood volume in Alzheimer's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014;34(4):654-659.

12. Visser PJ, Scheltens P, Verhey FR,et al. Medial temporal lobe atrophy and memory dysfunction as predictors for dementia in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. J Neurol 1999;246(6):477-485.

13. Wirth M, Pichet Binette A, Brunecker P, Kobe T, Witte AV, Floel A. Divergent regional patterns of cerebral hypoperfusion and gray matter atrophy in mild cognitive impairment patients. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017;37(3):814-824.

14. Jack CR, Jr., Knopman DS, Jagust WJ,et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer's pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol 2010;9(1):119-128.

15. Mazza M, Marano G, Traversi G, Bria P, Mazza S. Primary cerebral blood flow deficiency and Alzheimer's disease: shadows and lights. J Alzheimers Dis 2011;23(3):375-389.

16. Love S, Miners JS. Cerebral hypoperfusion and the energy deficit in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol 2016;26(5):607-617.

17. Duan W, Sehrawat P, Balachandrasekaran A,et al. Cerebral Blood Flow Is Associated with Diagnostic Class and Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2020;76(3):1103-1120.

18. Apostolova LG, Green AE, Babakchanian S,et al. Hippocampal atrophy and ventricular enlargement in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2012;26(1):17-27.

19. Carmichael OT, Kuller LH, Lopez OL,et al. Cerebral ventricular changes associated with transitions between normal cognitive function, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2007;21(1):14-24.

20. Driscoll I, Davatzikos C, An Y,et al. Longitudinal pattern of regional brain volume change differentiates normal aging from MCI. Neurology 2009;72(22):1906-1913.

21. Thompson PM, Hayashi KM, De Zubicaray GI,et al. Mapping hippocampal and ventricular change in Alzheimer disease. Neuroimage 2004;22(4):1754-1766.

22. Raji CA, Lopez OL, Kuller LH, Carmichael OT, Becker JT. Age, Alzheimer disease, and brain structure. Neurology 2009;73(22):1899-1905.

Figures