2654

Hyperperfusion in middle-aged individuals with genetic risk of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease1Department of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 3Centre for Dementia Prevention, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 4Ohio University, Athens, OH, United States, 5Institute of Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin, University of Dublin, Dublin, United Kingdom, 6Division of Brain Science, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, United Kingdom, 7Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, 8INSERM, Montpellier, France, 9University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Arterial spin labelling

Extensive brain hypoperfusion is well-established in people with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, mixed findings have emerged during the pre-symptomatic disease stage. In this study, we used arterial spin labelling (ASL) MRI in middle-aged, cognitively normal participants from the PREVENT-Dementia study to evaluate cerebral perfusion differences between carriers and non-carriers of the apolipoprotein ε4 (APOE4) allele. The ASL spatial coefficient of variation (CoV) was used as a proxy for arterial transit time (ATT) delays. We found hyperperfusion in APOE4 carriers which was not accompanied by increased spatial CoV, suggesting that the observed hyperperfusion is not driven by ATT delays.Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterised by marked atrophy in many brain regions and hypoperfusion, both changes particularly affecting the temporo-parietal cortex [1]. However, there is evidence from presymptomatic populations at midlife with increased risk for developing future dementia of increased cerebral blood flow (CBF) [2-4]. The presymptomatic or ‘preclinical’ disease period is the period during which there are no cognitive symptoms, which become apparent in the prodromal disease stage. Risk stratification in the preclinical period usually relies on several AD risk factors, including dementia family history, presence of elevated AD-related fluid or PET imaging markers or carriership of the apolipoprotein ε4 (APOE4) gene. Cognitively normal APOE4 carriers have been shown to demonstrate altered perfusion, compared to age-matched controls (carriers of APOE2 and APOE3 alleles) [2-4]. A potential explanation is that when using arterial spin labelling (ASL), hyperperfusion could be attributed to intravascular signal contamination. Not all ASL sequences allow for the quantification of arterial transit time (ATT) or acquire a cerebral perfusion measure insensitive to such variations. Recently, it has been shown that the spatial coefficient of variation (CoV) of the ASL signal, can be used as a proxy for ATT [5]. In this study we first determined, using data from the PREVENT-Dementia study [6, 7], whether APOE4 carriers had altered CBF compared to non-carriers, and secondly, determined whether alterations in CBF may be confounded by a higher spatial CoV.Methods

563 cognitively normal middle-aged participants in the PREVENT-Dementia study were scanned at 3T Siemens scanners (Prisma, Prisma fit, Verio, Skyra) in four study sites (West London, Cambridge, Oxford, Edinburgh) using a 2D ASL echo planar imaging sequence with the following characteristics: PICORE Q2TIPS – 50 pairs of control/tagged and one calibration image, TR = 2.5s, TE = 11ms, 14 slices, inversion time = 1.8s, bolus duration = 700ms (225 participants) and 1675ms (338 participants), flip angle = 90o, voxel size 3.0x3.0x6.0mm. A high resolution T1-weighted acquisition was also used (Magnetization prepared rapid-echo (MPRAGE) - TR = 2300ms, TE = 2.98ms, 160 slices, flip angle = 9°, voxel size = 1x1x1mm) in the present study. The MPRAGE image was segmented to gray matter (GM), white matter (WM) and cerebrospinal fluid with CAT12. GM and WM maps were registered to the ASL space and used for partial volume correction (PVC). The oxford_asl pipeline was used for processing of the scans, applying motion correction, calibration and spatial priors [8-10]. The boundary-based registration of FSL was used for registration of ASL to the T1 data and vice-versa. PVC CBF images were registered to the MNI space and the final voxel resolution was 2mm. A mask containing GM voxels where all participants had good quality data and brain coverage was created (Figure 1A,C). An upper and lower threshold for voxel CBF values was applied (150 and 4 ml/100g/min respectively). The group average GM mask was thresholded at 25% and was used for final masking. Voxel-wise comparisons were run using FSL’s randomise [11] with age, sex, years of education, bolus duration and study center (coded as a categorical variable) as additional nuisance regressors. The threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) method was used and 5000 permutations were applied; the level of significance was set to the adjusted p < = 0.05 after Family Wise Error rate correction (FWER).Results

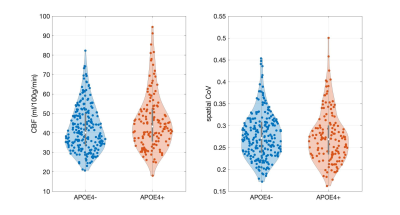

375 scans were of good quality and artifact-free, 233 belonged to non-carriers (mean age 51.9 ± 5.4, 66.5% females, 51.9% with dementia family history) and 142 to APOE4 carriers (mean age 50.4 ± 5.6, 68.3% females, 62.7% with dementia family history). APOE4 carriers were significantly younger compared to non-carriers (p = 0.02). Higher CBF was observed in APOE4 carriers (t = 2.70; p = 0.01) in a cluster covering mainly frontotemporal regions (Figure 1B,D). Within this hyperperfusion cluster, the spatial CoV was quantified as the standard deviation over the mean of CBF values, and it did not differ between the groups (t = -0.65; p = 0.51) (Figure 2).Discussion

Hyperperfusion has previously been reported in carriers of the APOE4 gene [2-4]. Additionally, there is evidence of a positive association between CBF and markers of AD-related proteins such as amyloid [12]. The observed hyperperfusion might be attributed to antagonistic pleiotropy effects or might hint towards the presence of an underlying resting vascular compensation mechanism in APOE4 carriers. The fact that spatial CoV was not higher in APOE4 carriers suggests that hyperperfusion is unlikely an ‘arterial transit artifact’ and potentially reflects actual higher perfusion.Conclusions

Hyperperfusion in APOE4 carriers has been reported in several studies. Given accumulating evidence regarding vascular changes in early disease stages, it is now important to acquire a deeper understanding of the reasons for this increased blood flow. In this study we have shown that middle-aged APOE4 carriers demonstrate hyperperfusion and using the spatial CoV of the ASL signal, we further demonstrated that hyperperfusion was not accompanied by a higher spatial CoV which is linked to prolonged ATT. In future studies inclusion of ASL sequences allowing for quantification of ATT will allow for a more detailed investigation of regional differences in both CBF and ATT between APOE4 carriers and non-carriers.Acknowledgements

We thank the PREVENT-Dementia participants and the DeNDRoN specialty within the Clinical Research Network for help with recruitment and participant assessments.References

1. Zhang, H., et al., Cerebral blood flow in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 2021. 71: p. 101450.

2. Dounavi, M.-E., et al., Evidence of cerebral hemodynamic dysregulation in middle-aged APOE ε4 carriers: The PREVENT-Dementia study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, 2021.

3. Wierenga, C.E., et al., Interaction of age and APOE genotype on cerebral blood flow at rest. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2013. 34(4): p. 921-935.

4. Wang, R., et al., Impact of sex and APOE epsilon4 on age-related cerebral perfusion trajectories in cognitively asymptomatic middle-aged and older adults: A longitudinal study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2021: p. 271678X211021313.

5. Mutsaerts, H.J., et al., The spatial coefficient of variation in arterial spin labeling cerebral blood flow images. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2017. 37(9): p. 3184-3192.

6. Ritchie, C.W. and K. Ritchie, The PREVENT study: A prospective cohort study to identify mid-life biomarkers of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. BMJ Open, 2012. 2(6): p. 1-6.

7. Ritchie, C.W., K. Wells, and K. Ritchie, The PREVENT research programme-A novel research programme to identify and manage midlife risk for dementia: The conceptual framework. International Review of Psychiatry, 2013. 25(6): p. 748-754.

8. Chappell, M.A., et al., Partial volume correction of multiple inversion time arterial spin labeling MRI data. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 2011. 65(4): p. 1173-1183.

9. Chappell, M.A., et al., Variational Bayesian Inference for a Nonlinear Forward Model. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 2009. 57(1): p. 223-236.

10. Groves, A.R., M.A. Chappell, and M.W. Woolrich, Combined spatial and non-spatial prior for inference on MRI time-series. NeuroImage, 2009. 45(3): p. 795-809.

11. Winkler, A.M., et al., Permutation inference for the general linear model. NeuroImage, 2014. 92: p. 381-397.

12. Fazlollahi, A., et al., Increased cerebral blood flow with increased amyloid burden in the preclinical phase of alzheimer's disease. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2020. 51(2): p. 505-513.

Figures