2647

Multi-parametric MRI Characterization of the Aging Squirrel Monkey as a Model of Sporadic Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy1NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2UT - MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Alzheimer's Disease, Aging, Non human primate

The current study seeks to identify neuroimaging biomarkers in a unique squirrel monkey (SQM) as a spontaneous model of cerebral amyloid angiopathy both in vivo and ex vivo using conventional MRI metrics in young and geriatric SQM cohorts and demonstrate the utility of quantitative R2* to map age-related differences in SQM neuropathology cross-sectionally and longitudinally.Introduction

Premature translation of promising immunotherapeutic approaches for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) from mice to humans has led to a high failure rate in clinical trials [1,2]. Major drawbacks of current treatments include limited effectiveness against cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) and an increased incidence of CAA-linked complications, such as amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) [3,4]. Squirrel monkeys (SQMs), new world primates with a maximum lifespan of ~ 25 years, are a unique non-human primate model (NHP), which unlike other NHPs, develops extensive age-associated CAA that is more prominent than parenchymal Aß deposits [5,6]. The growing recognition of CAA contribution to clinical decline and CAA-related complications in current clinical trials underscore the utility of the SQM model for studying CAA pathology development. Neuroimaging can play a key role in noninvasively detecting and monitoring disease progression in conjunction with histological methods. The current study seeks to identify neuroimaging biomarkers in order to help characterize and monitor age and disease-associated neuropathological changes in the SQM model.Methods

3 groups of SQMs with age ranging from 5 years old (=4), 16-17 years old (n=5) and 20-23 years old (n=12) were examined. All MRI scanning was performed in vivo at the UT/MD Anderson Cancer Center and ex vivo at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine on a similar 7-Tesla Bruker 7030 Biospec scanner interfaced to an Avance 3-HD console. A CP Tx/Rx birdcage RF coil (ID=86-mm) was used to accommodate the SQM body and enable full head coverage. The imaging protocol consisted of the following pulse sequences performed in vivo and when possible subsequently ex vivo, in separate sessions, in order to limit the anesthetic burden for each subject scanned as follow: 1) multigradient echo sequence (MGE, 8 Echoes, TE/ES= 2.96/4.0-ms TR=41-ms, FA= 13°, FOV= 38.4 × 25.6 × 25.6-mm, Matrix=384 × 256 × 256; Acq. Time= 45-min, NRep = 3, Tot. scanning= 2h30-min); 2) 2D T2-w Turbo-spin-echo (TSE, 1TFac=10, TE=36-ms, TR=3200-ms) and 3) 2D FLAIR (TFac=10, TE=35-ms, TR=3200-ms, TI=1557-ms for in vivo and TI=1150-ms for ex vivo to account for T1 alteration due to fixative). The two latter sequences were acquired in 4 consecutive datasets for full head coverage totaling 80-min for each sequence. Subsequent volumetric measurements of brain anatomical regions were performed from echo averaged MGE 3D dataset in order to boost both the SNR and CNR and ease anatomical morphometry by transforming brain volume into individual subject’s native MRI space, providing us with complete animal-specific regional volumes using MRtrix3 [7]. Immunohistochemistry was subsequently performed to characterize the neuropathological underpinnings of MRI abnormalities.Results

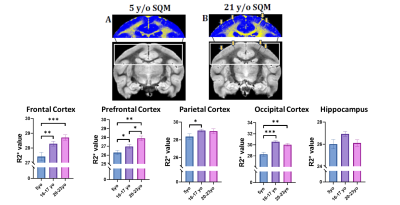

Our preliminary regional brain volume assessment revealed significant decreases in the prefrontal cortex and cingulum (one-way ANOVA, Bonferroni, **p < 0.01). Frontal and occipital cortex did not display significant changes in volume (Fig. 1). Ventricular enlargement was not observed (data not shown). Additional regions and subject analyses are ongoing. Notably, significant R2* differences quantified both through Atlas- and ROI-based analyses were observed between the young and the two older cohorts in various cortical brain regions (Fig. 2). Specifically R2*s increase were observed in several cortical regions (one-way ANOVA) with no significance in hippocampus. Additional regions and subjects analyses are underway.Both in vivo and ex vivo T2-w TSE and FLAIR helped identify spontaneous asymmetric hyperintensities commonly attributed to vasogenic edema (termed ARIA-E) exclusively in geriatric SQMs (21-23yrs) suggesting advanced pathology. Histological assessment of region-matched sections revealed Iba1 microgliosis, as well as immunoreactivity for decreased MBP when compared to the contralateral side. Aß immunohistochemistry (6E10/4G8) confirmed presence of CAA in the affected regions. Pronounced extravascular fibrinogen (FGG) immunoreactivity was detected in the gray matter in close proximity to the WM lesion area.Disussion & Conclusion

We examined the utility of R2* brain mapping under 200-µm isotropic spatial resolution as a quantitative biomarker of amyloid ß-related pathology including iron deposition, amyloid ß lesions, hemorrhaging. The same image dataset proved valuable to assess brain volumetric analysis among the three different SQM age cohorts. Importantly, the R2* increase preceded amyloid related imaging abnormalities associated with vasogenic edema detected with T2-w FSE and FLAIR as signal hyperintensities, which corresponds to histopathological features commonly present in advanced AD patients and following immunotherapies. Our findings help validate the use of SQMs as a model for testing the safety and efficacy of current immunotherapeutic approaches and studying the pathogenesis and possible long-term consequences of amyloid related imaging abnormalities. Our pixel-wise isotropic brain R2* mapping proved valuable for assessing retrospectively all anatomical brain regions both quantitatively and through a volumetric analysis where we were able to detect SQM age differences in diseased relevant regions. The study of aged SQM with naturally occurring Aß related pathologies visible by MRI may represent a sensitive in vivo model for testing the safety of current immunotherapeutic approaches, providing the community with an effective NHP model for studying the pathogenesis and possible long-term consequences of ARIA. The use of this advantageous NHP model is important to achieve efficienttranslation to human clinical trials.Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by Alzheimer’s Association - AARG-16-440596 NIH grants - R01NS102845, R21AG073305, R21NS127091, R01NS128190.MRI imaging was performed both at UT-MD Anderson Cancer Center and at the the NYU Langone Health Preclinical Imaging Core. The latter is a shared resource partially supported by the NIH/SIG 1S10OD018337-01, the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center Support GrantNIH/NCI 5P30CA016087 and the NIBIB Biomedical Technology Resource Center Grant NIH P41 EB017183.References

1. Drummond E, Wisniewski T. Alzheimer's disease: experimental models and reality. Acta neuropathologica. 2017;133(2):155-75. PMID: 28025715; PMCID: PMC5253109.

2. Banik A, Brown RE, Bamburg J, Lahiri DK, Khurana D, Friedland RP, Chen W, Ding Y, Mudher A, Padjen AL, Mukaetova-Ladinska E, Ihara M, Srivastava S, Padma Srivastava MV, Masters CL, Kalaria RN, Anand A. Translation of Pre-Clinical Studies into Successful Clinical Trials for Alzheimer's Disease: What are the Roadblocks and How Can They Be Overcome? Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2015;47(4):815-43. PMID: 26401762.

3. Banerjee G, Carare R, Cordonnier C, Greenberg SM, Schneider JA, Smith EE, Buchem MV, Grond JV, Verbeek MM, Werring DJ. The increasing impact of cerebral amyloid angiopathy: essential new insights for clinical practice. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2017;88(11):982-94. Epub 2017/08/28. PMID: 28844070

4. Sperling RA, Jack CR, Jr., Black SE, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM, Hyman BT, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies W, Bednar MM, Black RS, Brashear HR, Grundman M, Siemers ER, Feldman HH, Schindler RJ. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: Recommendations from the Alzheimer's Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(4):367-85.

5. Heuer E, Jacobs J, Du R, Wang S, Keifer OP, Cintron AF, Dooyema J, Meng Y, Zhang X, Walker LC. Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities in an Aged Squirrel Monkey with Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy. Journal of Alzheimer's disease : JAD. 2017;57(2):519-30. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160981. PMID: 28269776.

6. Patel AG, Nehete PN, Krivoshik SR, Pei X, Cho EL, Nehete BP, Ramani MD, Shao Y, Williams LE, Wisniewski T, Scholtzova H. Innate immunity stimulation via CpG oligodeoxynucleotides ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease pathology in aged squirrel monkeys. Brain : a journal of neurology. 021;144(7):2146-65.

7. Tournier JD, Smith R, Raffelt D, Tabbara R, Dhollander T, Pietsch M, Christiaens D, Jeurissen B, Yeh CH, Connelly A. MRtrix3: A fast, flexible and open software framework for medical image processing and visualisation. Neuroimage. 2019 Nov 15;202:116137.

Figures