2640

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN VASCULAR REACTIVITY AND MICROSTRUCTURAL WHITE MATTER INTEGRITY IN DUTCH-TYPE CEREBRAL AMYLOID ANGIOPATHY1Radiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands, 2Neurology and Neurosurgery, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands, 3LMU Klinikum, München, Germany, 4Neurology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands, 5Image Sciences Institute, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Diffusion Tensor Imaging, PSMD

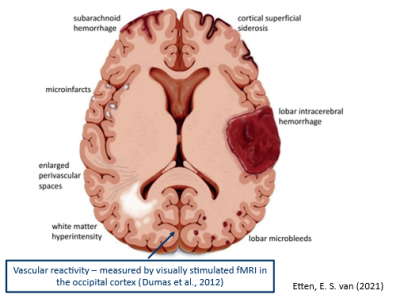

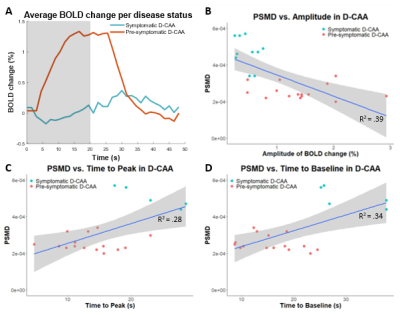

Vascular reactivity is an early marker of Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA), but its relation to structural brain damage remains unclear. We aimed to study this relationship in Dutch-type CAA (D-CAA; genetic form of CAA): vascular reactivity and microstructural white matter integrity were studied through visually stimulated fMRI and ‘Peak width Skeletonized Mean Diffusivity (PSMD)’. Reduced BOLD amplitude, delayed time to peak, and delayed time to baseline were significantly related to a higher PSMD (β=-1.15e-02, β =1.08e-05, β=8.64e-06, respectively). These results indicate that vascular reactivity and microstructural white matter integrity may deteriorate hand-in-hand in D-CAA.Introduction

Cerebral Amyloid Angiopathy (CAA) is one the leading etiologies of intracerebral hemorrhages in the elderly1. Dutch-type CAA (D-CAA) is an autosomal dominant hereditary form of CAA that is caused by a genetic mutation on the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene2. D-CAA can be confirmed through genetic testing, which enables studying the early presymptomatic phase of the disease, together with the symptomatic phase. In general, D-CAA is considered as a model for sporadic CAA. Vascular reactivity is an early marker of CAA3,4, but its relation to structural brain damage remains unclear. The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between reactivity alterations and microstructural white matter integrity measured by the diffusion measure ‘Peak width Skeletonized Mean Diffusivity (PSMD)’ in (pre-)symptomatic D-CAA mutation carriers.Methods

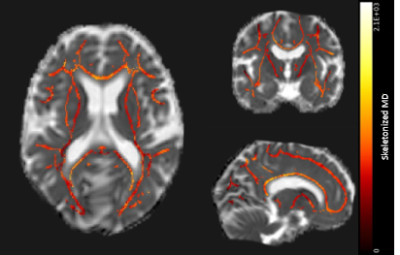

Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI; TE/TR 76/8194ms, FA 90°, 48 slices, FOV 220x220x120mm, voxel size 1.72x1.72x2.5mm, 45 gradient directions with b-value 1200s/mm2, 1 baseline image with b-value 0s/mm2, scan duration ~6:30 min) and reactivity measurements by visually stimulated fMRI (TE/TR 38/1500, FA 78°, 18 slices, 0.5mm interslice gap, FOV 210x177x59mm, voxel size 2.5x2.5x2.81mm, 224 dynamics, scan duration ~5:40 min) in the V1 of the visual cortex were acquired at 3Tesla in 25 D-CAA mutation carriers (mean 45±13.3yrs, range 28-71yrs, 64% women; 15 pre-symptomatic). The visual stimulus paradigm of the fMRI scan consisted of 7 blocks of an 8Hz flashing radial black and white checkerboard pattern, for 20s, followed by a grey screen for 28s3. Based on a trapezoid fit to the Blood-Oxygen-Level-Dependent (BOLD) response, we calculated normalized amplitude, time to peak (TTP), and time to baseline (TTB) of the BOLD response3. When the amplitude was too low, timing parameters TTP and TTB were not calculated. Based on the DTI, robust and fully automated PSMD was calculated5 (Figure 2). Associations between the vascular reactivity measures (amplitude, TTP, and TTB) and PSMD were tested using linear regression analyses (Figure 3B-D).Results

BOLD amplitude was decreased and PSMD, TTP, and TTB were increased in symptomatic versus presymptomatic D-CAA mutation carriers (Figure 3). Amplitude, TTP, and TTB are significantly related to PSMD values (β=-1.15e-02, p<.001; β =1.08e-05, p=.009; β=8.64e-06, p=.004, respectively). When looking only at the presymptomatic D-CAA mutation carriers, these relations are no longer statistically significant.Discussion and conclusion

Reduced vascular reactivity as depicted by reduced BOLD amplitude, and delayed TTP and TTB is related to microstructural white matter brain damage assessed through increased PSMD. This relationship indicates that vascular and microstructural white matter integrity loss go hand-in-hand in D-CAA. When looking only at the presymptomatic phase, the found effects are no longer statistically significant. Thus, the effects give insight into the disease progression and how vascular reactivity and microstructural white matter integrity progress from the presymptomatic to the symptomatic phase. With this cross-sectional study no causal relation can be proven.Acknowledgements

M.R. Schipper was funded by the TRACK D-CAA consortium consisting of Biogen, Alnylam, and researchers from Leiden, Boston, and Perth.

N. Vlegels was funded by the Heart Brain Connection Consortium.

References

1. Aguilar, M.I. and T.G. Brott, Update in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. The Neurohospitalist, 2011. 1(3): p. 148-159.

2. Bakker, E., et al., DNA diagnosis for hereditary cerebral hemorrhage with amyloidosis (Dutch type). Am J Hum Genet, 1991. 49(3): p. 518-21.

3. Dumas, A., Dierksen, G.A., Edip Gurol, M., Ann Neurol. 2012, 72(1): p. 76-81.

4. Opstal, A.M. van, Rooden, S. van, Harten, T.W. van, Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16(2): p. 115-122.

5. Baykara, E., Gesierich, B., Adam, R. Ann Neurol. 2016, 80(4): p. 581-592.

Figures