2634

Comparative evaluation of DKI and DTI in detecting white matter microstructural alterations in early-blind adolescents1Shenzhen Mental Health Center/Shenzhen Kangning Hospital, Shenzhen, China, 2GE Healthcare, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Adolescents

Blind people is a natural bio-model for the investigation of neural plasticity. Diffusion-based MRI techniques are powerful probes for characterizing the effects of disease and neural development on tissue microstructure. This study compared diffusion Kurtosis Imaging (DKI) metrics and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) metrics to explore white matter microstructural changes and neural plasticity in early-blind adolescents (EBAs). The results demonstrate microstructural complexity reduction and coexistence of neural reorganization and compensatory development process induced by visual deprivation in EBAs. And the DKI metrics are more sensitive in detecting changes in crossing fibers and pathology and development of disease than DTI metrics.

Introduction

Due to the visual deprivation, blind people is a natural bio-model for the investigation of neural plasticity. Neuroimaging studies, particularly the diffusion-based MRI methods, are powerful probes for characterizing the effects of disease and neural development on tissue microstructure. Compared to conventional diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) based on Gaussian diffusion model, diffusion kurtosis imaging (DKI) is expanded towards quantification of non-Gaussian water diffusion, which is closer to the physiological state and could be more sensitive in tissue characterization than DTI[1]. This study aimed to investigate the white matter (WM) microstructural changes and neural plasticity of DKI metrics in early-blind adolescents (EBAs) and to compare them with DTI metrics.Method

The DKI data and 3D high-resolution T1-weighted structural image of 23 EBAs (15 males and 8 females; age range 11-18, 14.80±2.07 years) and 20 age- and gender-matched normal-sighted controls (NSCs; 9 males and 11 females; age range 11-19, 14.46±2.62 years) were acquired. DKI was done using single-shot echo planar imaging sequence with b values of 0, 1000 and 2000 s/mm2 along 25 directions. By using the FMRIB Software Library (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/), DKI data were processed for motion correction, eddy current correction, and generated b0 image of each subject. Then, DKI parameter maps, including three tensor maps, i.e., axial diffusivity (AD), radial diffusivity (RD), and fractional anisotropy (FA), and three specific kurtosis maps, i.e., axial kurtosis (AK), radial kurtosis (RK), and mean kurtosis (MK), were derived from Diffusion Kurtosis Estimator software (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/dke/). After that, T1 anatomical image of each subject was first registered to b0 image using SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) with a six degree-of-freedom transform. Then the co-registered T1 images were non-linearly normalized from individual space to MNI 2 mm space. Next, all the DKI related quantitative mappings were also transformed to the MNI space, which were followed by smoothing with a 6 mm full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel. Finally, 50 different WM fiber tracts masks (ICBM-152)[2] were used to extract mean DTI and DKI metrics values for each participant. Statistically, two-sample t-test were performed to compare the differences of DTI and DKI metrics between two groups, and a p≤0.001 was considered to be significant. To see the relationship between significant diffusional parameters and age, Pearson’s correlation analysis was calculated in EBA group.Results

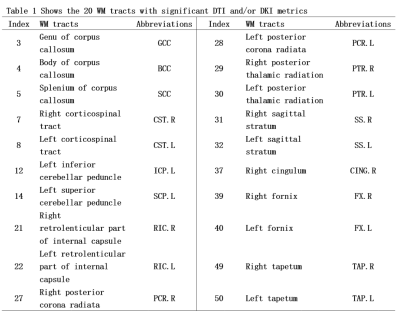

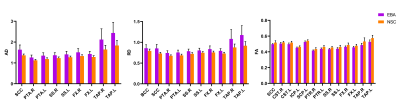

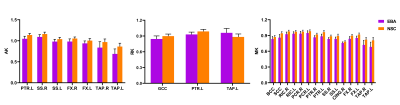

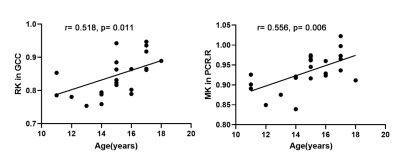

Two-sample t-test revealed significant increased AD and RD in body and genu of corpus callosum, bilateral posterior thalamic radiation, fornix and tapetum, increased RK in left tapetum, and decreased FA, AK, RK, and MK in corpus callosum, bilateral corticospinal tracts, left superior and inferior cerebellar peduncle, bilateral retrolenticular part of internal capsule, posterior corona radiate, posterior thalamic radiation, fornix and tapetum in EBAs compared to NSCs (p< 0.001). (Table 1, Figure 1&2). Pearson’s correlation analysis showed significant correlation between RK of genu corporis callosi and age (r=0.518, p=0.011), and between MK in right posterior corona radiata and age (r=0.556, p=0.006) in EBA. (Figure 3)Discussion and conclusion

As conventional diffusion tensor metrics, AD and RD measure the extent of water diffusion occurring parallel and perpendicular to the fiber, respectively, and FA tends to represent WM integrity. Increased AD and RD reflect degeneration or deterioration of the axonal and myelin integrity, respectively. Similarly, AK and RK measures the kurtosis along the parallel and perpendicular to the principle water diffused direction[3]. MK is defined as the average of kurtosis along all directions of diffusion gradients. Decreased kurtosis metrics reveal reduced diffusion restriction and tissue complexity[4]. In this study, we found similar changes of DTI metrics in body and splenium of corpus callosum, bilateral posterior thalamic radiation, sagittal stratum, fornix, and tapetum in EBA group compared to NSC group. These regions were related to the cognitive, emotional, visual and other information processing. However, the changes of DKI metrics was different. MK reductions occurred across more extensive WM tracts than DTI metrics, such as in the internal capsule, posterior corona radiata and cingulum. These tracts have cross-fiber concentrations. AK decreased in posterior thalamic radiation, sagittal stratum, fornix and tapetum, and RK decreased in genu of corpus callosum and posterior thalamic radiation, indicating a reduction in the corresponding axon and myelin complexity in these regions, respectively. Additionally, Pearson’s correlation analysis showed the positive correlation between RK in genu of corpus callosum and age, and between MK in right posterior corona radiate and age in EBAs. The results suggest that the structural complexity of these WM tracts increases with age. Since the posterior brain continues to develop during adolescence, this result may imply that visual deprivation leads to the coexistence of neural reorganization and compensatory development process in the brain of EBA. Our result also suggest that DKI metrics are more sensitive in detecting pathology and development of disease than DTI metrics.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Shenzhen Fund for Guangdong Provincial High-level Clinical Key Specialties (SZGSP013).References

[1] Steven A J, Zhuo J, Melhem E R. Diffusion kurtosis imaging: An emerging technique for evaluating the microstructural environment of the brain[J]. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2014, 202(1): W26-33.

[2] Mori S, Oishi K, Jiang H, et al. Stereotaxic white matter atlas based on diffusion tensor imaging in an icbm template[J]. Neuroimage, 2008, 40(2): 570-582.

[3] Wu E X, Cheung M M. Mr diffusion kurtosis imaging for neural tissue characterization[J]. NMR Biomed, 2010, 23(7): 836-848.

[4] Blockx I, Verhoye M, Van Audekerke J, et al. Identification and characterization of huntington related pathology: An in vivo dki imaging study[J]. Neuroimage, 2012, 63(2): 653-662.

Figures

Figure 1. Group differences of DTI metrics, i.e., axial diffusivity (AD), radial diffusivity (RD), and fractional anisotropy (FA), between early-blind adolescents (EBA) and normal-sighted controls (NSC) groups (p<0.001). The abbreviations of WM tracts can be referred in Table 1.

Figure 2. Group differences of DKI metrics, i.e., axial kurtosis (AK), radial kurtosis (RK) and mean kurtosis (MK), between early-blind adolescents (EBA) and normal-sighted controls (NSC) groups (p<0.001). The abbreviations of WM tracts can be referred in Table 1.

Figure 3. The Pearson correlation between abnormal DKI metrics and age in EBAs. RK, radial kurtosis; MK, mean kurtosis; GCC, genu of corpus callosum; PCR.R, right posterior corona radiate.