2633

Sensitivity of magnetic resonance elastography to white matter alterations in a rat model of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders

Katrina A. Milbocker1, L. Tyler Williams2, Ian F. Smith1, Diego A. Caban-Rivera2, Samuel Kurtz3,4, Matthew D.J. McGarry5, Elijah Van Houten4, Curtis L. Johnson1,2, and Anna Y. Klintsova1

1Dept. of Psychological & Brain Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 2Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 3Laboratorie de Mécanique et Génie Civil, CNRS, Université de Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 4Département de Génie Mécanique, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 5Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, United States

1Dept. of Psychological & Brain Sciences, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 2Dept. of Biomedical Engineering, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 3Laboratorie de Mécanique et Génie Civil, CNRS, Université de Montpellier, Montpellier, France, 4Département de Génie Mécanique, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 5Thayer School of Engineering, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, Preclinical

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) produces spatially-resolved maps of brain tissue mechanical properties by estimating parameters, such as stiffness and viscosity, via inverse solution of the underlying equations of motion. When measured in the brain, estimated properties from MRE detect effects of disease or interventions with high fidelity and relate to functional outcomes, making it a potentially invaluable technique in neuroradiology. Application of MRE in white matter (WM) tracts is limited. To evaluate the sensitivity of MRE to WM alterations, this study compared values of total brain stiffness and damping ratio derived from MRE scanning of rats with impaired WM development.Introduction

Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) of the brain estimates the stiffness and viscosity of neural tissues via imaging of displacements from gentle head vibration and inverse solution of the underlying equations of motion. While MRE has been used to investigate structural changes to brain regions clinically, use of this technique for in vivo imaging in preclinical rodent studies of white matter pathology is sparse, impeding its role in therapeutic development and disease progression research1,2. To test the sensitivity of preclinical MRE to WM pathology and outcomes of behavioral interventions in rodents, we collected a series of repeated in vivo MRE scans in a rat model of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD).FASD, a continuum of neurodevelopmental disorders, results from gestational alcohol exposure and leads to impaired executive function, visuospatial processing, sensory-motor integration, and learning/memory deficits3. Notably, alcohol exposure during the brain growth spurt, a period of rapid parenchymal growth during the onset of central nervous system myelination, delays the trajectory of WM myelination, ultimately contributing to impaired executive function and visuospatial processing in children and youth with FASD7-9. Similarly, rats exposed to alcohol during the rat brain growth spurt exhibit reduced WM myelination in adolescence and disrupted spatial working memory in adulthood10,11. Notably, increasing aerobic exercise in adolescence stimulates WM myelination in humans and rats13,14 and has been shown to mitigate impairments to neuronal architecture in rodent models of FASD4. We hypothesized that aerobic exercise would stimulate WM myelination in adolescent rats exposed to alcohol during the brain growth spurt. MRE scans were obtained immediately post-intervention in adolescence and again in adulthood to examine the acute and lasting effects of intervention on WM elastography in alcohol-exposed and control rats.

Methods

We performed MRE scans immediately following the intervention period in adolescence (postnatal day 45) and approximately one month later in young adulthood (postnatal day 70). We used a well-established rat model of FASD wherein female Long-Evans rat pups were either intubated and received alcohol in milk substitute producing blood alcohol concentrations of 300-400 mg/dL daily (alcohol exposed, AE; treatment condition) or sham-intubated with no liquid administration during the rat brain growth spurt (SI; sham condition). Once weaned, adolescent rats from each treatment group were randomly selected to remain in the homecage (SH; socially-housed sedentary control condition) or rehoused in modified cages with attached running wheels for 12-days voluntary exercise intervention (WR). Following the intervention period, intervention-exposed rats were rehoused in home cages and the first MRE scans were acquired (postnatal day 45). A second set of MRE scans was acquired approximately one month later in young adulthood (postnatal day 70); see Figure 1.MRE data were acquired with a custom echoplanar imaging (EPI) sequence with a 9.4T Bruker Biospec scanner. A piezoelectric actuator was attached to a bite bar to deliver vibrations at 800 Hz to anesthetized rats maintained on 1-3% isoflurane in oxygen and at 32-36 degrees Celsius for the total 1.5 hour scan protocol. MRE imaging parameters included: TE/TR = 60/3400 ms; 20x20 mm FOV; 80x80 matrix; 40 slices, 0.5 mm thick; 0.25x0.25x0.50 mm resolution. Maps of mechanical properties, including stiffness and damping ratio, were estimated from displacement images with nonlinear inversion (NLI) formulated without boundary conditions5. Following scanning in young adulthood, rats were perfused and brain tissue was collected for quantification of myelinating oligodendrocytes in the corpus callosum. We predicted that the integrity of the oligodendrocyte matrix could contribute to brain stiffness or damping ratio in WM.

Results

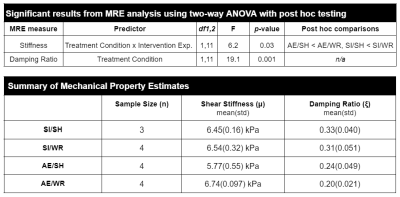

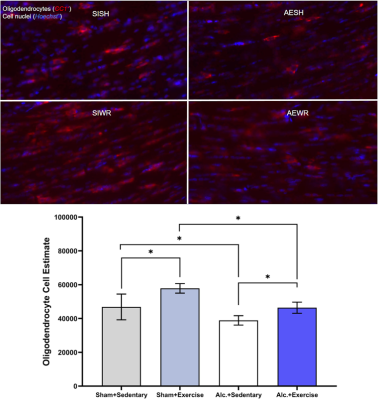

Results from the first set of scans following intervention exposure in adolescence indicate that there was a significant interaction between treatment condition and intervention exposure on brain stiffness (F1,11 = 6.2, p = 0.03). Post hoc analysis with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons revealed that stiffness was reduced in AE/SH rats; intervention exposure mitigated this effect (AE/WR). Moreover, there was a significant main effect of treatment on the damping ratio of the whole brain wherein AE reduced damping ratio in both the WR and SH groups (F1,11 = 19.1, p < 0.001; Figure 2, 3). Lower damping ratio could indicate delayed maturity of WM in adolescence after AE2.Preliminary histological analysis of oligodendrocyte count in the corpus callosum demonstrated that it is reduced in AE/SH female rats on postnatal day 45. Reduced oligodendrocyte count could be reflected in both lower stiffness and lower damping ratio, as they are thought to represent microstructural composition and organization, respectively12. Adolescent WR immediately increased the number of oligodendrocytes in WM in AE rats such that the population was comparable to SI levels (Figure 4). These cellular changes support the observed overall changes to brain stiffness.

Discussion and Conclusions

We show that MRE protocols can be adapted for preclinical scanning of anesthetized rodents, and these protocols exhibit a high degree of sensitivity for the detection of structural changes to WM in vivo. In the adolescent brain, whole brain stiffness was altered by the etiology of a neurodevelopmental disease (FASD) as well as following exercise intervention. These findings are convergent with the histological analysis of the oligodendrocyte matrix and indicate that MRE may be useful in the in vivo examination of acute alterations to WM structure.Acknowledgements

NIH/NIAAA R01 AA027269-01 (Klintsova), NIH 2P20GM10365 (University of Delaware Center for Biomedical and Brain Imaging; Klintsova and Johnson), NIH/NIBIB R01 EB027577 (Johnson)References

- Bayly P V., Garbow JR. Pre-clinical MR elastography: principles, techniques, and applications. J Magn Reson. 2018;291:73-83.

- Bigot M, Chauveau F, Beuf O, Lambert SA. Magnetic resonance elastography of rodent brain. Front Neurol. 2018;9:1-8.

- Delgorio et al. Structure-Function Dissociations of Human Hippocampal Subfield Stiffness and Memory Performance. Journal of Neuroscience. 2022; 42(42) 7957-7968.

- Helfer et al. The effects of exercise on adolescent hippocampal neurogenesis in a rat model of binge alcohol exposure during the brain growth spurt. Brain Research. 2009; 1294 1-11.

- McGarry et al. Multiresolution MR elastography using nonlinear inversion. Medical Physics. 2012; 39: 6388-6396.

- McIlvain et al. Mapping brain mechanical property maturation from childhood to adulthood. Neuroimage. 2022; (263) 1053-8119.

- Hoyme et al. Updated Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosing Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Pediatrics. 2016; 138(2) 20154256.

- Wozniak and Muetzel. What Does Diffusion Tensor Imaging Reveal About the Brain and Cognition in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders? Neuropsychology Review. 2011; 21 133-147.

- Treit et al. Longitudinal MRI Reveals Altered Trajectory of Brain Development during Childhood and Adolescence in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013; 33(24) 10098 –10109.

- Milbocker et al. Reduced and delayed myelination and volume of corpus callosum in an animal model of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders partially benefit from voluntary exercise. Scientific Reports. 2022; 12.

- Newville et al. Acute oligodendrocyte loss with persistent white matter injury in a third trimester equivalent mouse model of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Glia. 2017; ;65:1317–1332.

- Sack et al. Structure-sensitive elastography: on the viscoelastic powerlaw behavior of in vivo human tissue in health and disease. Soft Matter. 2013; 9: 5672-5680.

- Tomlinson et al. Behavioral experiences as drivers of oligodendrocyte lineage dynamics and myelin plasticity. Neuropharmacology. 2016; 110 548-562.

- Ruotsalainen et al. Physical activity, aerobic fitness, and brain white matter: Their role for executive functions in adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2020; 42 100765.

Figures

Figure 1. Experimental timeline depicting the timing of: 1) alcohol exposure/sham intubation which targets the rat brain growth spurt, 2) in vivo scan acquisition on postnatal day (PD) 45 and 70, and 3) exposure to aerobic intervention in adolescence.

Figure 2. Representative shear stiffness (μ) and damping (ξ) maps from each of the four study groups: sham intubated/social housing (SI/SH), sham intubated/wheel running (SI/WR), alcohol exposed/social housing (AE/SH), and alcohol exposed/wheel running (AE/WR).

Figure 3. Summary of MRE property results. Two-way ANOVA analysis revealed a significant interaction between treatment condition and intervention exposure on stiffness wherein WR increased stiffness the most in SI rats. There was a main effect of treatment condition on damping ratio such that it was reduced by AE. Table 2 shows the group averages for shear stiffness and damping ratio.

Figure 4. Example images of immunocytochemical stained oligodendrocytes with the corresponding statistical analysis comparing the number of oligodendrocytes in corpus callosum between groups following intervention exposure. Groups: sham intubated/social housing (SI/SH, gray), sham intubated/wheel running (SI/WR, periwinkle), alcohol exposed/social housing (AE/SH, white), and alcohol exposed/wheel running (AE/WR, blue). Bars: 土 SEM. *p < .05

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2633