2610

Assessment of the effects of coronary artery disease on brain oxygen extraction fraction using quantitative susceptibility mapping.1Physics Department, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2Centre Epic and Research Center, Montreal Heart Institute, Montreal, QC, Canada, 3Department of Biomedical Science, Faculty of Medicine, Université de Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 4PERFORM Centre, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5BrainLab, Hurvitz Brain Sciences Program, Sunnybrook Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6Department of Psychology, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 7Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 8Department of Medicine, Université de Montreal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 9Research Center, Institut Universitaire de Gériatrie de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Blood vessels, Oxygenation

Here we investigated the effect of coronary artery disease (CAD) on the brain oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) using quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM). Our results, in a pilot dataset, show that OEF was significantly higher in CAD patients than in healthy controls in the caudate nucleus. This may be the result of declining cerebrovascular health in CAD patients in this region. However, since the caudate nucleus is iron-rich, this difference may also be interpreted as iron deposition as CAD has a known neuroinflammatory effect. Future work will investigate the impact of CAD on other metabolic and vascular components of brain health.

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most prevalent form of cardiovascular1. Chronic vascular diseases are also known to be associated with cerebrovascular damage. Brain function depends on sustained oxygen delivery. The balance between oxidative metabolism and O2 delivery from blood can be assessed using measures of oxygen extraction fraction (OEF). In turn, the two components that form OEF are cerebral blood flow (CBF) and oxygen consumption, measured by Cerebral Metabolic Rate of Oxygen Consumption (CMRO2). OEF is a valuable biomarker that is affected in several disease conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease2 and stroke3. However, it is currently unknown whether CAD affects brain oxidative metabolism. While it is challenging to measure OEF noninvasively and accurately, recent advances in Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping (QSM) make it now possible to measure OEF in the brain’s draining veins from MRI phase data. Since deoxyhemoglobin, predominantly present in veins, is paramagnetic, QSM allows extracting veins, and the susceptibility value within venous voxels is directly proportional to OEF. Recent work has shown the promise of QSM mapping to study venous structure5 and OEF4 in health and disease3. Here, we investigated the effects of CAD on OEF in comparison to healthy aging individuals with the use of QSM.Methods

The study included 29 CAD patients and 17 healthy controls (HC). MRI data acquisitions were performed at the Montreal Heart Institute (MHI), using a 3T Siemens Skyra MRI scanner equipped with a 32-channel array coil. QSM data were acquired using a 3D multi-echo gradient echo sequence with TR/TE1/TE2/TE3/TE4/flip angle = 20 ms/6.92 ms/13.45 ms/19.28 ms/26.51 ms/9°, 0.7 x 0.7 mm in-plane and 1.4 mm slice thickness. The first echo time data was fully flow-compensated in all three directions to mitigate blood flow artifacts in QSM maps. The phase and magnitude data from all coil channels were collected uncombined and recombined offline. Raw unwrapped phase data were combined and wrapped using the ROMEO toolbox6. The magnitude images were then combined by channel averaging and a brain mask was extracted using FSL BET7. The resultant mask and unwrapped phase images were used as input for the Total-generalized-variation (TGV) algorithm for QSM reconstruction, which includes background field removal and dipole inversion in a single iteration8. The resultant QSM maps were referenced to CSF QSM values in ventricles to derive relative QSM maps. Then, we used a novel Recursive Ridge Filtering (RRF) method9 to extract draining veins, as well as partial volume maps to correct final OEF values in small veins. Whole brain GM OEF values were extracted from venous voxels for each individual, as well as within the following regions of interest: the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes, the cerebellum, thalamus and caudate nucleus. A one-way ANCOVA test was then employed in R, utilizing sex and age as covariates, to compare OEF values in each ROI between the CAD and control groups. Tukey’s post-hoc test was employed to control for family-wise error where there were significant group differences. A significance level of p < 0.05 was employed.Results

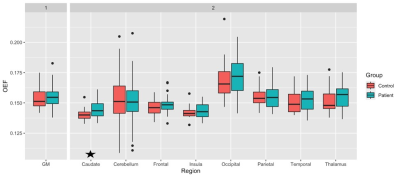

Table 1 demonstrates some demographic information of our preliminary sample. There were no statistical differences between CAD and HC for age, education, or the number of males and females in each group (p > 0.05). The one-way ANCOVA revealed that there was a statistically significant difference between the OEF values of CAD and HC within the caudate nucleus (F(1,40) = 4.51, p = 0.040), where CAD patients had significantly greater OEF in this region. No other region demonstrated a significant difference between the CAD patients and HC (p > 0.05). Figure 1 shows the average regional OEF values in CAD and HC groups, respectively.Discussion

Results revealed a significant difference in OEF within the caudate nucleus, whereby CAD patients showed a higher OEF than HC, potentially reflecting an unbalance between metabolism and vascular health in this region. This is consistent with reduced perfusion in vascular disease10. However, these results must be interpreted with caution given that the caudate nucleus is iron-rich. Cardiovascular diseases are known to be associated with neuroinflammation11 and this neuroinflammation can cause iron deposition in subcortical structures12. Finally, the lack of significant differences in other regions may reflect the preliminary nature of this analysis (i.e., a smaller sample size), however data acquisition of this project is still ongoing. As OEF values in patients were found to be systematically, though non-significantly, higher, it is likely that the future analyses of the complete dataset will yield greater power and thus increase the ability to detect differences in other regions between the groups. Moreover, the investigation of whether additional parameters, such as CBF, CMRO2 and venous structure are affected by CAD, will be permitted in future work with this project.Consclusion

This study explores the impact of CAD on brain oxygenation. In our preliminary sample, we identified an OEF difference in the caudate. This difference could reflect a difference in oxygenation or iron deposits due to neuroinflammation. Future analyses of the full sample will also investigate the impact of CAD on OEF, CBF, CMRO2, venous structure and iron deposition, providing a further understanding of the effects of CAD on cerebral metabolic and vascular health compared to healthy aging.Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of Paule Samson, MR technologist, Julie Lalongé, research assistant and medical electrophysiology technologist, and of all the staff of the EPIC center that has contributed to this project. We also want to thank all students and research assistants who have helped in data acquisitions: Roni Zaks, Robert Hovey, Stephanie Beram, Alexandre bailey, Agathe Godet and Kathia Saillant and the research participants who took part in this study.

SAT was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR: FBD 175862).

CJG was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation New Investigator Award and J.M. Barnett fellowship, the Michal and Renata Hornstein Chair in Cardiovascular Imaging, and the Heart and Stroke Foundation Grant-inAid G-17-0018336.

LB was supported by Mirella and Lino Saputo Research Chair in Cardiovascular Health and the Prevention of Cognitive Decline from the Universite de Montreal at the Montreal Heart Institute.

References

[1] Anazodo, U. C., Shoemaker, J. K., Suskin, N., Ssali, T., & Wang, D. J. (2015). Impaired Cerebrovascular Function in Coronary Artery Disease Patients and Recovery Following Cardiac Rehabilitation. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2015.00224

[2] Liu, Y., Dong, J., Song, Q., Zhang, N., Wang, W., Gao, B., Tian, S., Dong, C., Liang, Z., Xie, L., & Miao, Y. (2021). Correlation Between Cerebral Venous Oxygen Level and Cognitive Status in Patients With Alzheimer's Disease Using Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping. Frontiers in neuroscience, 14, 570848. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.570848

[3] Fan, A. P., Khalil, A. A., Fiebach, J. B., Zaharchuk, G., Villringer, A., Villringer, K., & Gauthier, C. J. (2020). Elevated brain oxygen extraction fraction measured by MRI susceptibility relates to perfusion status in acute ischemic stroke. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism: official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism, 40(3), 539–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271678X19827944

[4] Fan, A. P., Bilgic, B., Gagnon, L., Witzel, T., Bhat, H., Rosen, B. R., & Adalsteinsson, E. (2014). Quantitative oxygenation venography from MRI phase. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 72(1), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.24918

[5] Huck, J., Wanner, Y., Fan, A. P., Jäger, A. T., Grahl, S., Schneider, U., Villringer, A., Steele, C. J., Tardif, C. L., Bazin, P. L., & Gauthier, C. J. (2019). High resolution atlas of the venous brain vasculature from 7 T quantitative susceptibility maps. Brain structure & function, 224(7), 2467–2485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-019-01919-4

[6] Dymerska, B, Eckstein, K, Bachrata, B, et al. Phase unwrapping with a rapid opensource minimum spanning tree algorithm. Magn Reson Med. 2021; 85: 2294– 2308. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.28563

[7] Smith S. M. (2002). Fast robust automated brain extraction. Human brain mapping, 17(3), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.10062

[8] Langkammer, C., Bredies, K., Poser, B. A., Barth, M., Reishofer, G., Fan, A. P., Bilgic, B., Fazekas, F., Mainero, C., & Ropele, S. (2015). Fast quantitative susceptibility mapping using 3D EPI and total generalized variation. NeuroImage, 111, 622–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.02.041

[9] P. -L. Bazin, V. Plessis, A. P. Fan, A. Villringer and C. J. Gauthier, "Vessel segmentation from quantitative susceptibility maps for local oxygenation venography," 2016 IEEE 13th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 2016, pp. 1135-1138, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISBI.2016.7493466

[10] Alosco, M. L., Gunstad, J., Jerskey, B. A., Xu, X., Clark, U. S., Hassenstab, J., Cote, D. M., Walsh, E. G., Labbe, D. R., Hoge, R., Cohen, R. A., & Sweet, L. H. (2013). The adverse effects of reduced cerebral perfusion on cognition and brain structure in older adults with cardiovascular disease. Brain and behavior, 3(6), 626–636. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.171

[11] Díaz, H. S., Toledo, C., Andrade, D. C., Marcus, N. J., & Del Rio, R. (2020). Neuroinflammation in heart failure: new insights for an old disease. The Journal of physiology, 598(1), 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP278864

[12] Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):388-405. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5

Figures