2597

Feasibility of muscle template creation using tensor based registration1Radiology, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Muscle, Diffusion Tensor Imaging

In this study, the aim is to show the feasibility of generating a per-muscle architecture template using a combination of muscle shape and muscle tensor registration. Additionally, the use of a generalized muscle template to identify between-subject differences will be explored. The tensor-based registration does allow for better alignment of internal muscle structures which is not possible using registration based on distance maps alone.Introduction

Muscle architecture is the main determinant of muscle function. Diffusion tensor-based tractography, although challenging, allows for three-dimensional quantification of this muscle architecture (1). A single value for fascicle length and pennation angle per muscle does not capture regional variations within a muscle (2) since multipennate muscles can have multiple compartments with different properties (3). When assuming that muscle fibres cannot diverge muscle architecture can be described using Laplacian flow if the muscle shape and attachment areas are known (4,5). To allow the regional analysis of muscle architecture Bolsterlee proposed a framework for the analysis of three-dimensional shape and architecture using muscle templates (6). Within this framework, tensors were not realigned based on the shape deformations and no internal structures were used for muscle alignment (7). Combining the template framework and that muscle architecture is determined by its shape a general template can be made for each muscle and such a template can be used to simplify muscle architecture analysis. In this study, the aim is to show the feasibility of generating a per-muscle architecture template using a combination of muscle shape and muscle tensor registration. Additionally, the use of a generalized muscle template to identify between-subject differences will be explored.Methods

For this study we used previously published calf DTI data of 5 volunteers in 3 different ankle positions (15° dorsiflexion, 0° neutral and 30° plantarflexion) which were acquired twice, resulting in 30 datasets (8). All data processing and analysis were done using QMRITools (9). Processing of the DTI data comprised denoising, motion and eddy current correction and anatomical alignment. The tensors were fitted using an iWLLS solver using outlier removal.For muscle template creation, each muscle was manually segmented and registered to a common space using a reference distance map (6) using PCA-based group-wise image registration (10), and tensor realignment (7). Next, an average muscle tensor dataset was created to which each muscle was registered using all 6 log Euclidian (11) tensor components which allows aligning the internal muscle architecture between subjects as is shown in figure 1. The muscle template can then be transformed back to subject space using the same tensor-based registration and tensor realignment allowing subject-specific analysis with point-to-point correspondence to the template.

The muscle architecture is quantified using tract-based analysis. For each muscle and template, 100k fibre tracts were generated (FA: 0.1-0.5; step: 1mm; angle: 10°) which were then amended to exclude tendinous tissue using tract density (12). After tractography tracts were fitted with a 3rd-order polynomial (13) and per voxel fibre length and angle maps were created. The fibre architecture between subjects and ankle positions was compared in template and subject space to explore the effects of template-based analysis.

Results

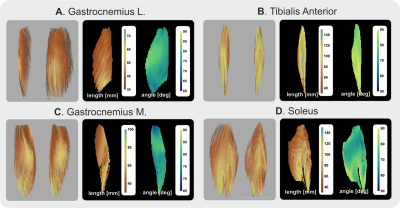

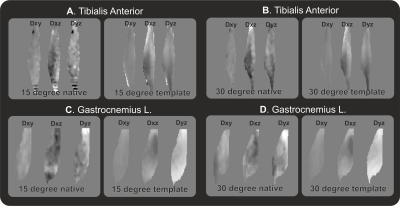

Template creation using shape only was feasible, as was also previously shown (6), as can be seen in figures 1 A and B. The tensor templates created per muscle are shown in figure 1 C. The template resembles the muscle architecture of those in the native subject space. The second step was to register the muscles to the template space tensor created using distance maps but this time using all 6 tensor elements of which the result can be seen in figure 1 D. Although the tensors are still blurred compared to those in the native subject space the muscle architecture is better defined as indicated by the red arrows.The analysis of fibre length and angle in the template space is shown in figure 2. The muscle architecture in template space still resembles the actual muscle architecture although details tend to be blurred out, which is most apparent in the soleus muscle where the anterior compartment is hard to recognize (3).

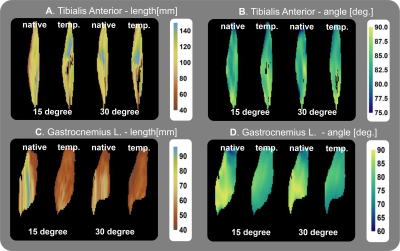

The created muscle tensor templates can be registered back to the native subject space as shown in figure 3. Overall the general architecture still resembles the one recognizable in the more noisy subject space. However, the quantitative assessment of muscle length and angle to not match the template muscle in native space and the original muscles, which is shown in figure 4.

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, the feasibility of generating a per-muscle architecture template using a combination of muscle shape and muscle tensor registration is shown. The current cohort is still small, with only 5 subjects each with 6 datasets. However, the tensor-based registration does allow for better alignment of internal muscle structures which is not possible using registration based on distance maps alone.The muscle architecture evaluation, although still qualitative for now, shows recognizable muscle architecture and the quantitative maps are in line with previous results. However, when registering the template back to the native space there are many differences. This can be due to the imperfect reconstruction of the native data or flaws in the registration.

Further work will involve increasing the database on which the template is based and also extending it to the upper leg muscles. Furthermore, the registration framework and architecture quantification need to be improved. In conclusion, the concept of template-based analysis seems to be valid, which will allow for a well-curated template per muscle reducing the effort needed for native architecture analysis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by VIDI research programme (project number: 18929) of the Dutch Research Council (NWO).

Great thanks to Bart Bolsterlee for the valuable discussions regarding muscle architecture analysis and to the collaborators of the original dataset.

References

1. Damon BM, Froeling M, Buck AKW, et al. Skeletal muscle diffusion tensor-MRI fiber tracking: rationale, data acquisition and analysis methods, applications and future directions. NMR Biomed 2017;30:e3563 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3563.

2. Heemskerk AM, Sinha TK, Wilson KJ, Ding Z, Damon BM. Repeatability of DTI-based skeletal muscle fiber tracking. NMR Biomed 2010;23:294–303 doi: 10.1002/nbm.1463.

3. Bolsterlee B, D’Souza A, Herbert RD. Reliability and robustness of muscle architecture measurements obtained using diffusion tensor imaging with anatomically constrained tractography. J Biomech 2019;86:71–78 doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2019.01.043.

4. Choi HF, Blemker SS. Skeletal Muscle Fascicle Arrangements Can Be Reconstructed Using a Laplacian Vector Field Simulation. PLoS One 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077576.

5. Handsfield GG, Bolsterlee B, Inouye JM, Herbert RD, Besier TF, Fernandez JW. Determining skeletal muscle architecture with Laplacian simulations: a comparison with diffusion tensor imaging. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 2017;16:1845–1855 doi: 10.1007/s10237-017-0923-5.

6. Bolsterlee B. A new framework for analysis of three-dimensional shape and architecture of human skeletal muscles from in vivo imaging data. J Appl Physiol 2022;132:712–725 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00638.2021.

7. Alexander DC, Pierpaoli C, Basser PJ, Gee JC. Spatial transformations of diffusion tensor magnetic resonance images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2001;20:1131–1139 doi: 10.1109/42.963816.

8. Mazzoli V, Oudeman J, Nicolay K, et al. Assessment of passive muscle elongation using Diffusion Tensor MRI: Correlation between fiber length and diffusion coefficients. NMR Biomed 2016;29:1813–1824 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3661.

9. Froeling M. QMRTools: a Mathematica toolbox for quantitative MRI analysis. J Open Source Softw 2019;4:1204 doi: 10.21105/joss.01204.

10. Huizinga W, Poot DHJ, Guyader JM, et al. PCA-based groupwise image registration for quantitative MRI. Med Image Anal 2016;29:65–78 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2015.12.004.

11. Arsigny V, Fillard P, Pennec X, Ayache N. Log-Euclidean metrics for fast and simple calculus on diffusion tensors. Magn Reson Med 2006;56:411–421 doi: 10.1002/mrm.20965.

12. Oudeman J, Mazzoli V, Marra MA, et al. A novel diffusion-tensor MRI approach for skeletal muscle fascicle length measurements. Physiol Rep 2016;4:e13012 doi: 10.14814/phy2.13012.

13. Damon BM, Ding Z, Hooijmans MT, et al. A MATLAB toolbox for muscle diffusion-tensor MRI tractography. J Biomech 2021;124:110540 doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110540.

Figures