2579

Investigating border zone hemodynamics with time-encoded super-selective pCASL in internal carotid and basilar artery perfusion territories1C.J. Gorter MRI Center, Department of Radiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Arterial spin labelling, Perfusion, super-selective, time-encoded, borderzones

The borders between cerebral perfusion territories are regions of the brain that are susceptible to infarction. In this study, time-encoded super-selective pCASL was implemented to study the hemodynamic properties of the border zones between the left internal carotid artery and basilar artery perfusion territories. Perfusion territories were well-defined with little-to-no detectable overlap. The longest arrival times were found at the border zones, compared to 'inland' of the perfusion region. Combining time-encoded with super-selective pCASL enables the simultaneous investigation of border zones and their arrival times.Introduction

Border zones are the locations at the periphery of flow territories of tissues fed by specific arteries. In the brain, the border zones are regions that are more susceptible to infarction, i.e. where white matter lesions more frequently occur. It is generally assumed that their arrival times are delayed1, and that this could be linked to the increased risk of hypoxic injury in cerebrovascular diseases2, but exactly how they are linked is unknown. Our understanding of the border zones between perfusion territories is limited by the lack of simultaneous measurements of arrival time and perfusion territory mapping. This can be achieved by combining time-encoded pCASL with super-selective pCASL3,4 to obtain vessel-specific and therefore perfusion-territory-specific information at multiple times, or post-label delays. This combination was implemented in this study and used for two purposes:- To investigate whether this is detectable overlap between left internal carotid artery (LICA) and basilar artery (BA) territories within the border zones.

- To investigate whether longer arrival time corresponds spatially to the border zone region between LICA and BA.

Methods

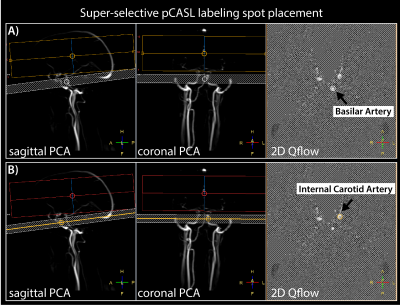

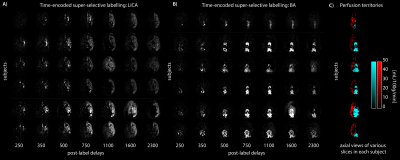

Six subjects (3 female/3male, mean age 27.5 ± 2.3 years) underwent MRI on an Achieva 3T MRI scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, Netherlands) with a 32-channel head-coil. Several surveys of the vasculature were performed for planning (Figure 1). Time-encoded super-selective pCASL was performed with a 2-shot segmented 3D-gradient and spin echo (3D-GRASE) readout. The matrix was 64 × 64 (RL x AP) with 18 slices (resolution 3.75 × 3.75 × 3.75 mm3), TSE factor of 25, slice oversampling factor 1.4, EPI echo train length of 15 and a shot length of 274 ms. The TR/TE was 4600/11 ms, which included WET pre-saturation pulses, 3950 ms Hadamard-encoded labelling blocks: 1900, 700, 500, 350, 250, 150, 100 ms; post-label delays: 250, 350, 500, 750, 1100, 1600, 2300 ms, 4 background suppression pulses, 16 dynamics, total scan duration of 21:28 minutes. The labelling focus was centred on the basilar artery for one sequence, and on the left internal carotid artery for the other super-selective pCASL sequence (Figure 1).Images were aligned and subtracted according to the Hadamard-8 matrix and averaged over the 16 dynamics. Masks were defined by thresholding the average of the last 3 post-label delays above the 95th percentile. Quantification of arrival time and cerebral blood flow (CBF) was done by fitting the timeseries per voxel to the Buxton model5 (also fitting T1 since this resulted in lower residuals). Although it is expected that labelling efficiency is lower in super-selective pCASL4, we still assumed a labelling efficiency of 0.85 in the fitting procedure, since our aim was to quantify arrival time. We did not expect CBF values to represent the actual perfusion, but used them for the purpose of displaying the perfusion territories (Figure 2). Long arrival times were defined as >95th percentile of the arrival time parameter map.

Results

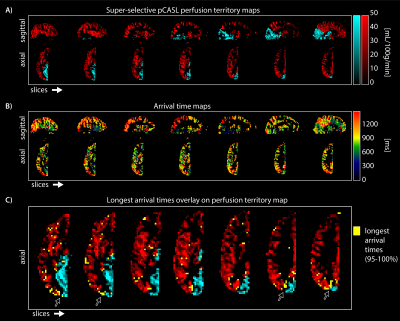

Perfusion territories between the LICA and BA differed slightly between participants. Figure 2 shows that participant in row one only had a left posterior territory perfusion fed by the basilar artery, while most other participants had left and right posterior territory perfusion fed by the basilar artery. Furthermore, the lateral ventricle choroid plexus was clearly visible in the basilar territory maps. This region is fed by the lateral posterior choroidal artery, a branch of the posterior cerebral artery.Aside from perfusion territories (Figure 3A) the arrival time parameter maps from LICA and BA territories showed spatial variation as hypothesised (Figure 3B); long arrival time voxels at the borders between territories. The longest arrival time voxels were displayed in yellow on top of the perfusion territory maps to show the co-localisation with the border zones (Figure 3C).

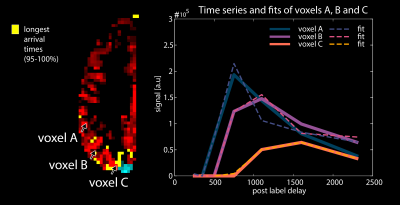

Figure 4. shows the quantitative parameters of voxels that were far from, or close to, the borders. The time series shows clear differences in arrival time as well as magnitude between the border zone-voxel and the distal voxels.

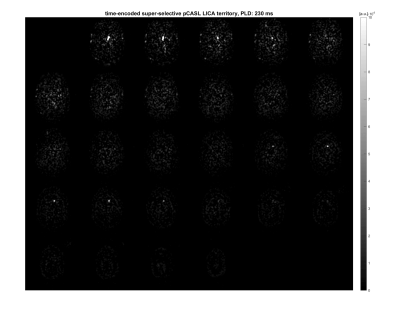

Figure 5. shows a movie over seven post-label delays of the perfusion territory fed by the LICA. It is clear that the posterior region is not perfused, as expected since only the LICA was labelled in this dataset, and implies that there is no overlap between the perfusion territories.

Discussion

In this work time-encoded pCASL and super-selective pCASL were combined to enable simultaneous measures of the hemodynamic aspects of the border zones and delineation of perfusion territories in the brain. Our results show well-defined territories with no overlap detected at this spatial resolution of 3.75 x 3.75 x 3.75 mm3. A 2D multi-slice read-out may be slightly more sensitive in terms of in-plane voxel size but 3D provides higher SNR, which was needed here to counteract the lower labelling efficiency we expected due to additional in-plane gradients for super-selective pCASL4 and the inhomogeneous labelling location6 at C4. While it is known that arrival times vary spatially across the brain1, the link to border zones has been made possible in this study by combining time-encoded with super-selective pCASL. In conclusion the longest arrival times were spatially colocalised with what we defined and detected here as the border zones.Acknowledgements

This work is part of the research programme Innovational Research Incentives Scheme Vici with project number 016.160.351, which is financed by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO).References

1. Hendrikse et al. Cerebral Border Zones between Distal End Branches of Intracranial Arteries: MR Imaging. Radiology 2008; 246(2): 339-655.

2. Stotesbury et al. Individual Watershed Areas in Sickle Cell Anemia: An Arterial Spin Labeling Study. Frontiers in Physiology 2022; 13:865391.

3. Helle et al. Superselective pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 2010; 64(3): 777-86.

4. Dai et al. Modified Pulsed-continuous arterial spin labeling for labeling of a single artery. Magn Reson Med. 2010; 64(4): 975–982.

5. Buxton et al. A General Kinetic Model for Quantitative Perfusion Imaging with Arterial Spin Labeling. Magn. Reson. Med. 1998; 40:383–396.

6. Teeuwisse et al. Arterial spin labeling at ultra-high field: All that glitters is not gold. Int J Imaging Syst Technol, 2010; 20(1): 62–70.

Figures