2575

APOE genotype-dependent sex differences in cortical hemodynamics measured with arterial spin labeling MRI1Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 3Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 4MGH Institute of Health Professions, Boston, MA, United States, 5MU School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, United States, 6Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, United States, 7NeuroGenomics and Informatics Center, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, United States, 8Hope Center for Neurologic Diseases, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, United States, 9Neuroimaging Research for Veterans Center, VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Arterial spin labelling, Aging

Identifying biomarkers that could characterize typical from atypical aging is crucial for understanding the aging process. One of the most significant genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s Disease, an age-related neurodegenerative disorder, is the presence of an apolipoprotein-E (APOE) ε4 allele. Here, we investigate the impact of APOE genotype on cortical hemodynamics in a large cohort of participants across the lifespan, accounting for interacting effects of age, sex, and cardiovascular risk. We found unique spatial patterns of cerebral blood flow and arterial transit time between males and females within distinct APOE genotypes, potentially indicating the presence of a complex interaction.Introduction

Altered cerebral physiology has been postulated to precede changes in brain structure and cognition that typically occur during the aging process1. Understanding whether these physiological changes may serve as early biomarkers for neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), is a crucial step towards characterizing typical from atypical aging. The Lifespan Human Connectome Project in Aging (HCP-A) contains a rich dataset across a typically aging cohort including imaging measures of perfusion and structure, as well as apolipoprotein-E (APOE) genotype sequencing and cardiovascular risk measures2. Previous work from the HCP-A consortium has demonstrated global decreases in grey matter cerebral blood flow (CBF) and increases in arterial transit time (ATT) across the aging trajectory3, but the contributions of APOE genotype and region-based differences have not been explored. As the presence of an APOE-ε4 allele represents a significant genetic risk factor for AD4, we investigated the relationship between APOE genotype and cerebral hemodynamics using the HCP-A cohort, whilst accounting for the potential interacting effects of age, sex and cardiovascular risk.Methods

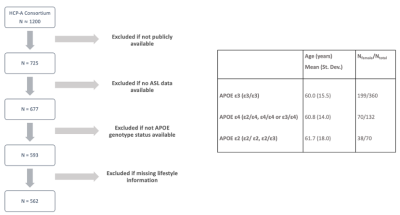

Participants. The publicly available dataset consisted of 562 individuals between 36–90+ years who had arterial spin labeling (ASL) data, lifestyle information, and genetic sequencing. We stratified the cohort into three groups based on APOE genotype: 1) homozygous APOE-ε3 (ε3/ε3), 2) either heterozygous (ε2/ε4, ε3/ε4) or homozygous (ε4/ε4) APOE-ε4 individuals, 3) either heterozygous (ε2/ε3) or homozygous APOE-ε2 (ε2/ε2). Further information on the cohort demographics can be seen in Figure 1 and have been previously reported2.Data acquisition. Four acquisition sites used matched optimized protocols to collect pseudo-continuous ASL data5. The acquisition parameters included labeling duration=1500 ms, five post-labeling delays (PLD)=200 ms (control/label pairs=6), 700 ms (pairs=6), 1200 ms (pairs=6), 1700 ms (pairs=10), and 2200 ms (pairs=15), multi-band 2D gradient echo echo-planar imaging (GRE-EPI) readout with TR=3580 ms, TE=19 ms, partial Fourier=6/8, SMS acceleration factor=6, total slices=60, spatial resolution=2.5×2.5×2.5 mm3, total acquisition time=5.5 min. Equilibrium magnetization (M0) images were acquired at the end of the scan. Two spin echo EPI scans with opposite phase encoding directions were also acquired for distortion correction, with TR=8000 ms, TE=40 ms, spatial resolution=2.5×2.5×2.5 mm3. A standard 0.8 mm resolution T1-weighted structural multi-echo MPRAGE image was also collected as previously described5.

Data processing and analysis. Image pre-processing included applying ‘TopUp’ for distortion correction6, motion correction with AFNI '3dvolreg'7, and multi-band artifact correction through slice interpolation. CBF and ATT quantification were performed using an approach similar to previous work4. Surface-based analysis was performed in Freesurfer8. CBF and ATT maps were registered to the T1-weighted image using boundary-based registration9, and partial volume correction was applied10. An average z-score was computed from medication-adjusted measures for cardiovascular risk11, which was included as a covariate alongside age in a general linear model analysis for the effects of sex and genotype. Surfaces were corrected using threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) with significance established with cluster-wise error correction (cwc) pcwc<0.05 after permutation testing with 1000 permutations with cluster-forming threshold of p=0.001 for multiple comparisons correction. Effect size maps were also devised to clarify the effect of sample size differences.

Results

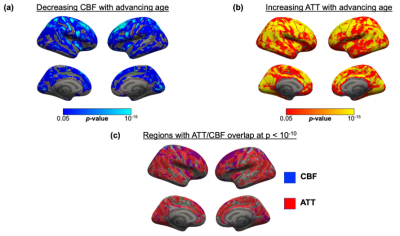

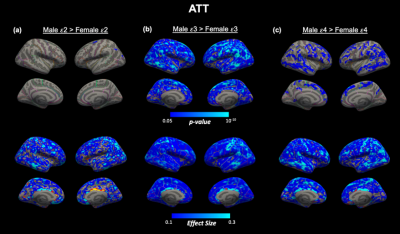

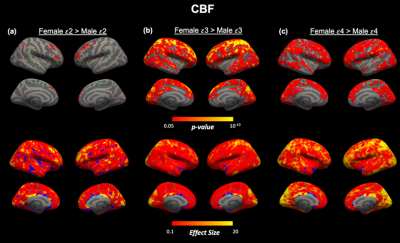

Perfusion associations with age. We confirmed previous findings by identifying a significant inverse age association with CBF and a significant positive age association with ATT across the cortex in the entire cohort (Figure 2a,b). Regions demonstrating particularly strong correlations with age (pcwc<10-10) were within the superior frontal lobe for CBF and across the frontal and temporal cortices for ATT. We found overlapping regions of most significant CBF decline and ATT incline with age in the rostral middle frontal cortex (Figure 2c).Within genotype sex differences. We did not identify any significant difference between APOE genotype or surface-based interaction effects between APOE genotypes within sex. However, we found unique spatial patterns of sex differences according to APOE genotype for both ATT (Figure 3) and CBF (Figure 4). The most significant sex differences (pcwc<10-6) in ATT were localized to the inferior parietal, lateral orbitofrontal and precentral regions for APOE-ε2, supramarginal and temporal regions for APOE-ε3 and inferior parietal and inferior temporal for APOE-ε4. For CBF, significant sex differences were in the rostral middle frontal region for APOE-ε2, superior parietal region for APOE-ε3 and supramarginal gyrus for APOE-ε4.

Discussion

Overlapping regions of significant CBF and ATT associations with advancing age could indicate areas that are vulnerable to neurodegeneration, potentially related to age-related vascular effects (e.g., arterial stiffening). The differing spatial patterns of sex differences according to APOE genotype could be indicative of an interaction effect of APOE with sex, as observed in previous studies12,13, such that 'at-risk' regions differ between sex according to genotype. For example, APOE-ε4 dosage has demonstrated an interaction effect with sex on tau deposition14. Further investigation with longitudinal data would benefit the validation of these findings.To conclude, we observed significant associations with age globally for ATT and CBF though the strength of associations was region-dependent. Stratifying according to genotype, whilst accounting for cardiovascular risk and age, demonstrated unique spatial patterns of sex differences according to genotype.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (R21AG072068, U01AG052564, and U01AG052564-S1) and the American Heart Association (19CDA34790002). This research was made possible in part by the computational hardware generously provided by the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center (https://www.masslifesciences.com/).References

1. Chen, J. J., Rosas, H. D., & Salat, D. H. (2013). The Relationship between Cortical Blood Flow and Sub-Cortical White-Matter Health across the Adult Age Span. PLOS ONE, 8(2), e56733.

2. Bookheimer, S. Y., Salat, D. H., Terpstra, M., Ances, B. M., Barch, D. M., Buckner, R. L., Burgess, G. C., Curtiss, S. W., Diaz-Santos, M., Elam, J. S., Fischl, B., Greve, D. N., Hagy, H. A., Harms, M. P., Hatch, O. M., Hedden, T., Hodge, C., Japardi, K. C., Kuhn, T. P., … Yacoub, E. (2019). The Lifespan Human Connectome Project in Aging: An overview. NeuroImage, 185, 335–348.

3. Juttukonda, M.R., Li, B., Almaktoum, R., Stephens, K.A., Yochim, K.M., Yacoub, E., Buckner, R.L. and Salat, D.H., 2021. Characterizing cerebral hemodynamics across the adult lifespan with arterial spin labeling MRI data from the Human Connectome Project-Aging. NeuroImage, 230, p.117807.

4. Tai LM, Thomas R, Marottoli FM, Koster KP, Kanekiyo T, Morris AW, Bu G. The role of APOE in cerebrovascular dysfunction. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:709-723.

5. Harms, M. P., Somerville, L. H., Ances, B. M., Andersson, J., Barch, D. M., Bastiani, M., Bookheimer, S. Y., Brown, T. B., Buckner, R. L., Burgess, G. C., Coalson, T. S., Chappell, M. A., Dapretto, M., Douaud, G., Fischl, B., Glasser, M. F., Greve, D. N., Hodge, C., Jamison, K. W., … Yacoub, E. (2018). Extending the Human Connectome Project across ages: Imaging protocols for the Lifespan Development and Aging projects. NeuroImage, 183, 972–984.

6. Smith, S.M., Jenkinson, M., Woolrich, M.W., Beckmann, C.F., Behrens, T.E., Johansen-Berg, H., Bannister, P.R., De Luca, M., Drobnjak, I., Flitney, D.E. and Niazy, R.K., 2004. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage, 23, pp.S208-S219.

7. Cox, R.W., 1996. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Computers and Biomedical research, 29(3), pp.162-173.

8. Fischl, B., Sereno, M. I., & Dale, A. M. (1999). Cortical Surface-Based Analysis: II: Inflation, Flattening, and a Surface-Based Coordinate System. NeuroImage, 9(2), 195–207.

9. Greve, D. N., & Fischl, B. (2009). Accurate and robust brain image alignment using boundary-based registration. NeuroImage, 48(1), 63–72.

10. Greve, D.N., Salat, D.H., Bowen, S.L., Izquierdo-Garcia, D., Schultz, A.P., Catana, C., Becker, J.A., Svarer, C., Knudsen, G.M., Sperling, R.A., and Johnson, K.A., 2016. Different partial volume correction methods lead to different conclusions: an 18F-FDG-PET study of aging. Neuroimage, 132, pp.334-343.

11. Robertson, T., Beveridge, G. and Bromley, C., 2017. Allostatic load as a predictor of all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the general population: Evidence from the Scottish Health Survey. PloS one, 12(8), p.e0183297.

12. Farrer, L.A., Cupples, L.A., Haines, J.L., Hyman, B., Kukull, W.A., Mayeux, R., Myers, R.H., Pericak-Vance, M.A., Risch, N. and Van Duijn, C.M., 1997. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. Jama, 278(16), pp.1349-1356.

13. Wang, R., Oh, J.M., Motovylyak, A., Ma, Y., Sager, M.A., Rowley, H.A., Johnson, K.M., Gallagher, C.L., Carlsson, C.M., Bendlin, B.B. and Johnson, S.C., 2021. Impact of sex and APOE ε4 on age-related cerebral perfusion trajectories in cognitively asymptomatic middle-aged and older adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism, p.0271678X211021313.

14. Yan, S., Zheng, C., Paranjpe, M.D., Li, Y., Li, W., Wang, X., Benzinger, T.L., Lu, J. and Zhou, Y., 2021. Sex modifies APOE ε4 dose effect on brain tau deposition in cognitively impaired individuals. Brain, 144(10), pp.3201-3211.

15. Cruchaga, C., Kauwe, J.S., Mayo, K., Spiegel, N., Bertelsen, S., Nowotny, P., Shah, A.R., Abraham, R., Hollingworth, P., Harold, D. and Owen, M.M., 2010. SNPs associated with cerebrospinal fluid phospho-tau levels influence rate of decline in Alzheimer's disease. PLoS genetics, 6(9), p.e1001101.

Figures