2574

Optimal PLD selection for White Matter perfusion measurements at 7T.1Radiology, C.J. Gorter MRI Center, Leiden Univeristy Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands, 2Radiology, Center for Image Sciences, Univeristy Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Arterial spin labelling, High-Field MRI

White matter (WM) perfusion measurements are challenging because of the generally lower perfusion in combination with a longer bolus arrival time (BAT). We investigated the use of long-PLD perfusion measurements at high-field (7T) to compensate for longer BAT in WM. We showed that 3D background suppressed FAIR at 7T with a PLD of 2300ms provides robust perfusion measurement in almost 80% of deep WM within 4min of scan time.Background:

Over the last years, flow-alternating-inversion-recovery (FAIR) ASL has proven to provide robust and sufficient gray matter (GM) perfusion SNR at 7T. However, white matter (WM) perfusion is known to be lower and to have longer bolus arrival times (BAT), both resulting in low SNR. Previously, it was shown at 3T that after 10min of scanning using background suppressed pCASL, 70% of the WM voxels showed significant perfusion signal[1]. High field strength could potentially improve WM perfusion measurements since relaxation of label is less severe due to longer T1 of blood, enabling longer post-label-delays (PLD) acquisitions to compensate for longer BAT in WM. However, more physiological noise will be present at higher field strength[2], emphasizing the need for good background suppression (BGS)[3]. Recently, at 7T, over 75% of voxels presented significant perfusion with 11min of scan time using real-time feedback 2D FAIR[4]. The aim of this study was to investigate whether long PLD 3D FAIR at 7T can provide more robust WM perfusion signal within a clinically acceptable scan time.Methods

Acquisition: FAIR time-resampled frequency offset corrected inversion (TR-FOCI)[5] RF-pulses and two BGS-pulses were applied in combination with five QUIPSS pulses equally spaced starting 800ms after labelling[3]. Images were acquired at PLDs ranging from 1300-3800ms with 500ms steps. A 3D EPI read-out (3x3x3mm voxels) was chosen to obtain proper and homogenous BGS over the entire imaging volume. Other imaging parameters were: FOV=210x210x51mm, TR/TE=6000/8.3ms, FA=20֯ dynamics=20 (and 30 for PLDs≥2800ms) with a total scan time of 4min (and 6min resp.) per PLD. Timings of the BGS-pulses were chosen to suppress GM, WM and CSF ≈90%. In addition, a proton density-weighted scan (M0) was acquired for quantification purposes and a MPRAGE was acquired as anatomical reference. 7 volunteers (4 female, age range 20-63y) were included in this study and all scans were acquired in pseudo-random order.Pre-Processing: Motion correction and co-registration of the ASL-images to the M0-scan were performed using SPM. T1-weighted anatomical images were segmented in GM- and WM-masks. The WM-mask was eroded multiple times to obtain masks to specifically target the deep WM with the longest BAT[1].

Post-Processing: ASL-images at each PLD, were quantified as proposed in the ASL consensus paper[6]. Additionally, the Buxton-curve was fitted to the complete multi-PLD dataset. The dynamic signal, per PLD, was tested voxel-wise with p=0.05 using a two-sided t-test against the null-hypothesis of perfusion being zero. tSNR was defined as the mean ASL-signal divided by the standard deviation over the averages (std). Similar as in [1], we calculated N, the required number of averages to observe significant perfusion: N=16xstd2/mean2.

tSNR , CBF, and percentage significantly perfused voxels, were compared for different PLDs, voxel-wise and on an ROI-level. After processing in native space, volumes were registered to MNI-space to visualize CBF, tSNR and the required number of averages on a group-level.

Results

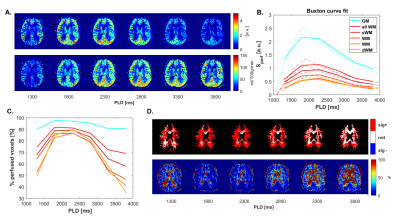

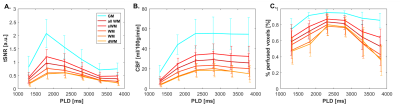

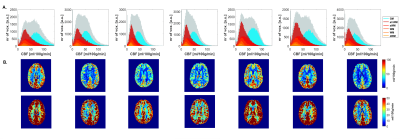

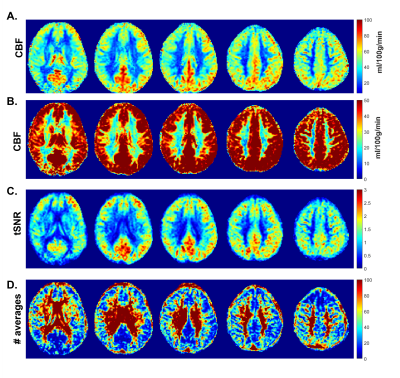

Fig.1. shows CBF-data for an example volunteer. Mean GM perfusion was 58.5±13.1, for all WM 31.8±6.6, and deep WM 21.0±5.8 ml/100g/min. tSNR and significantly perfused voxels across PLD are visualized in Fig.2. for a representative subject, and the group-average is plotted in Fig.3. CBF histograms and the other subjects are shown in Fig.4. GM tSNR was found to be highest for a PLD of 1800ms (p=0.009) and decreased linearly with PLD. In contrast, for all WM masks, the tSNR between PLDs 1800ms and 2300ms was plateauing. The percentage of significantly perfused voxels per PLD is shown in Fig.3.c. For WM, a parabolic trend is visible peaking around a PLD of 2300ms. Mean %perfused voxels, at the PLD of 2300ms was, for GM 95.3±3.4%, all WM 83.6±9%, and deep WM 79.9±13%. For GM, no difference in %perfused voxels was found in the range of 1800-2800ms. However, for deep WM, significant signal was found in a higher percent of voxels for a PLD of 2300 compared to 1800ms (p=0.0092), where no difference was found between 2300 and 2800ms (p=0.16). Lastly, in Fig.5. group-average CBF, tSNR, and required number of averages maps in MNI-space are shown.Discussion

3D FAIR 7T perfusion measurements were performed with a wide range in PLD to investigate WM perfusion. The observed mean GM perfusion value is in line with previous literature[1,4,6,7]. However, the mean WM perfusion found is slightly higher than in [1,4] but comparable to [7]. The highest %perfused voxels in the deep WM was found for a PLD of 2300 (79.9%) but this was not significantly different from 2800ms. This percentage is similar to that found in [4] for the total WM but within a shorter scan time. Since the tSNR of WM and especially GM (Fig.4.A) decreased with PLD, a PLD of 2300ms is recommended for WM perfusion measurements at 7T within clinically acceptable scan time.Limitations: A drawback of the 3D read-out approach is blurring in the slab-selection direction. This could be overcome by applying a flip-angle sweep. Quantification of the effect of blurring on this data set is required, but the eroding procedure is expected to provide a more conservative estimate of WM perfusion. The TR (6000ms) was limited by SAR, SAR-efficient inversion-pulses could reduce the TR considerably and result in even better perfusion estimates within this scan time.

Acknowledgements

TTW-ZonMW-SGF-LHS Human Measurement models grant # 18969-Virtual Cerebrovascular ResponsesReferences

[1] van Osch, M. J., Teeuwisse, W. M., van Walderveen, M. A., Hendrikse, J., Kies, D. A., & van Buchem, M. A. (2009). Can arterial spin labeling detect white matter perfusion signal?. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 62(1), 165-173.

[2] Teeuwisse, W. M., Webb, A. G., & van Osch, M. J. (2010). Arterial spin labeling at ultra‐high field: all that glitters is not gold. International Journal of Imaging Systems and Technology, 20(1), 62-70.

[3] Hirschler, L., Franklin, S. L., Schmid, S., Teeuwisse, W. M., van Osch, M. J. (2018). Background suppression is more important for ASL at higher magnetic field strength. ISMRM Annual Scientific Meeting 2018, Paris, France (Abstract No. 2160).

[4] Gardener, A. G., & Jezzard, P. (2015). Investigating white matter perfusion using optimal sampling strategy arterial spin labeling at 7 Tesla. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 73(6), 2243-2248.

[5] Hurley, A. C., Al‐Radaideh, A., Bai, L., Aickelin, U., Coxon, R., Glover, P., & Gowland, P. A. (2010). Tailored RF pulse for magnetization inversion at ultrahigh field. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine: An Official Journal of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 63(1), 51-58.

[6] Alsop, D. C., Detre, J. A., Golay, X., Günther, M., Hendrikse, J., Hernandez‐Garcia, L., ... & Zaharchuk, G. (2015). Recommended implementation of arterial spin‐labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: a consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 73(1), 102-116.

[7] Wu, W. C., Lin, S. C., Wang, D. J., Chen, K. L., & Li, Y. D. (2013). Measurement of cerebral white matter perfusion using pseudocontinuous arterial spin labeling 3T magnetic resonance imaging–an experimental and theoretical investigation of feasibility. PloS one, 8(12), e82679.

Figures

(5): Group-average maps in MNI space: (A,B) CBF, (C) tSNR and (D) number of required averages for a PLD of 2300ms.