2545

A consensus Protocol for task-free Anesthetized Rat functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Data Analysis

Roël Matthijs Vrooman1, Gabriel Desrosiers-Gregoire2,3, Gabriel Devenyi2,4, Yen-Yu Ian Shih5,6,7, Sung-Ho Lee5,6, Monica van den Berg8,9, Georgios Keliris8,9, and Joanes Grandjean1,10

1Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, RadboudUMC, Utrecht, Netherlands, 2Cerebral Imaging Centre, Douglas Mental Health University Institute, Verdun, QC, Canada, 3Integrated Program in Neuroscience, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 4Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5Center for Animal MRI, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States, 6Neurology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States, 7Biomedical Engineering, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States, 8Bio-imaging lab, University of Antwerp, Antwerpen, Belgium, 9µNEURO Research Centre of Excellence, University of Antwerp, Antwerpen, Belgium, 10Department for Medical Imaging, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands

1Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, RadboudUMC, Utrecht, Netherlands, 2Cerebral Imaging Centre, Douglas Mental Health University Institute, Verdun, QC, Canada, 3Integrated Program in Neuroscience, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 4Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 5Center for Animal MRI, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States, 6Neurology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States, 7Biomedical Engineering, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States, 8Bio-imaging lab, University of Antwerp, Antwerpen, Belgium, 9µNEURO Research Centre of Excellence, University of Antwerp, Antwerpen, Belgium, 10Department for Medical Imaging, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Acquisition, fMRI (resting state), Rat, Rodent

fMRI in rats is performed under diverse protocols that span different animal handling practices and preprocessing steps. The disparity in image acquisition and preprocessing hampers the interoperability and comparison of the results between studies. Importantly, it is unclear what factors lead to superior acquisition and detection of functional networks. We detail a consensus-based task-free fMRI acquisition protocol in the rat that has been validated in 21 datasets. Along with the animal handling protocol and MRI sequence, we provide a detailed path for data conversion, preprocessing, and analysis.Introduction

Animal experimentation is a cornerstone of neuroscience research (Homberg et al., 2021). Rodents, in particular rats, are commonly used for functional magnetic resonance imaging (Gozzi & Schwarz, 2016; Lee et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020) due to their nervous system structure bearing many similarities to the human brain (Mandino et al., 2019), ease of breeding, low maintenance, and availability of transgenic strains (Transgenic Model Creation Services | Charles River, n.d.). Importantly, invasive and terminal experiments in rodents allow for better causal inferences and relating brain-wide fMRI findings to cellular and molecular markers. Despite the utility of rodent models, the translation of the observation to humans remains a central issue. Unlike the wide availability of large human fMRI datasets and dedicated processing toolboxes, which have contributed to the harmonization of the acquisition and processing procedures (Esteban et al., 2019; Sudlow et al., 2015; Van Essen et al., 2012), fMRI in rodents is still performed under diverse protocols with different animal handling practices and preprocessing steps (Mandino et al., 2019). The disparity in the image acquisition and preprocessing hampers the interoperability and the comparison of the results between studies (Grandjean et al., 2022; Mandino et al., 2019). Importantly, it is unclear what factors lead to superior acquisition and detection of functional networks.Methods

To determine acquisition parameters leading to enhanced detection of functional networks, we have compared 65 task-free datasets acquired in rats representative of the local acquisitions from 46 participating laboratories (Grandjean et al., 2022). We determined the functional connectivity specificity within sensory networks for each scan (Grandjean et al., 2020). We then determined animal handling procedures associated with the connectivity outcomes. This information was then used to develop the StandardRat protocol applicable to both starting and experienced laboratories, equipped with both older and newer equipment. The StandardRat consensus protocol was developed in collaboration with the rat fMRI community and was independently tested in 21 datasets acquired in 20 research centers. Details of the protocol can be seen in Figure 1 and Table 1.Results/Discussion

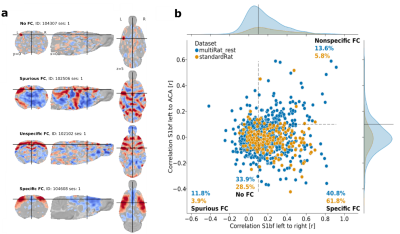

The newly developed protocol outperformed previous acquisitions by 50% according to the specificity metric used. This specificity metric is based on the assumption that within-network nodes should exhibit high functional connectivity, while nodes between functionally antagonizing networks (e.g., task positive and task negative networks) should present low or no functional connectivity. When data shows both these features, it can be said to have ‘specific functional connectivity’. This was analyzed by comparing the correlation between S1bf of the left and right hemisphere (within-network), to the correlation between S1bf to ACA (antagonizing networks) Examples of specific and unspecific correlation can be seen in Figure 2a. The prevalence of specific functional connectivity varies between studies as can be seen Figure 2b. However, when using the protocol described in the current paper it resulted in more specific connectivity compared to the original datasets (Figure 2b, 40.8 vs 61.8%). This protocol can thus add to the standardization of rodent fMRI imaging, thereby increasing its relevance and translational value.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

Esteban, O., Markiewicz, C. J., Blair, R. W., Moodie, C. A., Isik, A. I., Erramuzpe, A., Kent, J. D., Goncalves, M., DuPre, E., Snyder, M., Oya, H., Ghosh, S. S., Wright, J., Durnez, J., Poldrack, R. A., & Gorgolewski, K. J. (2019). fMRIPrep: A robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nature Methods, 16(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41592-018-0235-4Gozzi, A., & Schwarz, A. J. (2016). Large-scale functional connectivity networks in the rodent brain. NeuroImage, 127, 496–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.12.017Grandjean, J., Canella, C., Anckaerts, C., Ayrancı, G., Bougacha, S., Bienert, T., Buehlmann, D., Coletta, L., Gallino, D., Gass, N., Garin, C. M., Nadkarni, N. A., Hübner, N. S., Karatas, M., Komaki, Y., Kreitz, S., Mandino, F., Mechling, A. E., Sato, C., … Gozzi, A. (2020). Common functional networks in the mouse brain revealed by multi-centre resting-state fMRI analysis. NeuroImage, 205, 116278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116278Grandjean, J., Desrosiers-Gregoire, G., Anckaerts, C., Angeles-Valdez, D., Ayad, F., Barrière, D. A., Blockx, I., Bortel, A. B., Broadwater, M., Cardoso, B. M., Célestine, M., Chavez-Negrete, J. E., Choi, S., Christiaen, E., Clavijo, P., Colon-Perez, L., Cramer, S., Daniele, T., Dempsey, E., … Hess, A. (2022). StandardRat: A multi-center consensus protocol to enhance functional connectivity specificity in the rat brain (p. 2022.04.27.489658). bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.27.489658Homberg, J. R., Adan, R. A. H., Alenina, N., Asiminas, A., Bader, M., Beckers, T., Begg, D. P., Blokland, A., Burger, M. E., van Dijk, G., Eisel, U. L. M., Elgersma, Y., Englitz, B., Fernandez-Ruiz, A., Fitzsimons, C. P., van Dam, A.-M., Gass, P., Grandjean, J., Havekes, R., … Genzel, L. (2021). The continued need for animals to advance brain research. Neuron, 109(15), 2374–2379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2021.07.015Lee, S.-H., Broadwater, M. A., Ban, W., Wang, T.-W. W., Kim, H.-J., Dumas, J. S., Vetreno, R. P., Herman, M. A., Morrow, A. L., Besheer, J., Kash, T. L., Boettiger, C. A., Robinson, D. L., Crews, F. T., & Shih, Y.-Y. I. (2021). An isotropic EPI database and analytical pipelines for rat brain resting-state fMRI. NeuroImage, 243, 118541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.118541Liu, Y., Perez, P. D., Ma, Z., Ma, Z., Dopfel, D., Cramer, S., Tu, W., & Zhang, N. (2020). An open database of resting-state fMRI in awake rats. NeuroImage, 220, 117094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117094Mandino, F., Cerri, D. H., Garin, C. M., Straathof, M., van Tilborg, G. A. F., Chakravarty, M. M., Dhenain, M., Dijkhuizen, R. M., Gozzi, A., Hess, A., Keilholz, S. D., Lerch, J. P., Shih, Y.-Y. I., & Grandjean, J. (2019). Animal Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Trends and Path Toward Standardization. Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, 13, 78. https://doi.org/10.3389/fninf.2019.00078Sudlow, C., Gallacher, J., Allen, N., Beral, V., Burton, P., Danesh, J., Downey, P., Elliott, P., Green, J., Landray, M., Liu, B., Matthews, P., Ong, G., Pell, J., Silman, A., Young, A., Sprosen, T., Peakman, T., & Collins, R. (2015). UK Biobank: An Open Access Resource for Identifying the Causes of a Wide Range of Complex Diseases of Middle and Old Age. PLOS Medicine, 12(3), e1001779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779Transgenic Model Creation Services | Charles River. (n.d.). Retrieved November 9, 2022, from https://www.criver.com/products-services/research-models-services/genetically-engineered-model-services/transgenic-mouse-rat-model-creation?region=3696Van Essen, D. C., Ugurbil, K., Auerbach, E., Barch, D., Behrens, T. E. J., Bucholz, R., Chang, A., Chen, L., Corbetta, M., Curtiss, S. W., Della Penna, S., Feinberg, D., Glasser, M. F., Harel, N., Heath, A. C., Larson-Prior, L., Marcus, D., Michalareas, G., Moeller, S., … Yacoub, E. (2012). The Human Connectome Project: A data acquisition perspective. NeuroImage, 62(4), 2222–2231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.018Figures

Figure 1: Anesthesia and imaging protocol outline (a) and representative functional (left) and structural (right) scans from the standardRat dataset (b)

Figure 2: Examples of the functional connectivity categories (a) and the distribution of these categories over the database of 65 datasets (MultiRat_rest) compared to the standardRat protocol datasets (b)

Table 1: Structural and functional MRI protocol details (a) and field strength dependent variables (b)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/2545