2535

High-Frequency Resting-State Connectivity using Spectrally Segmented Regression of Movement, Physiological Noise and Spectral Residuals1Nuclear Engineering, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States, 2Nucelar Engineering, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States, 3Neurology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States, 4Physics and Astronomy, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Processing, fMRI (resting state)

Regression of filtering residuals is introduced to spectrally segmented regression of nuisance parameters in high-speed fMRI to enable the application of finite impulse response filters for spectral segmentation of regressors. This extension of our previously introduced method of spectrally and temporally segmented regression improves the removal of noise and mitigates the introduction of artefactual correlations in high frequency resting-state fMRI. Simulations and in-vivo data demonstrate significant advantages of spectrally segmented regression compared to whole-band regression when frequency-dependent errors are present in the regression model. High-frequency resting-state connectivity is detected with high sensitivity during normo-, hypo- and hypercapnic state.INTRODUCTION

The low frequency range of resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI) necessitates long scan times to segregate networks and introduces sensitivity to signal drift and network non-stationarity1-3. The detection of resting-state connectivity at frequencies above 0.3 Hz may provide increase spectral specificity and improve temporal stability4,5. However, concerns have been raised regarding the use of conventional whole-band regression techniques in the preprocessing of rapidly sampled fMRI data that may introduce artifactual high frequency connectivity6,7. We recently introduced spectrally and temporally segmented regression of motion parameters and physiological noise, which minimizes artifactual injection of low frequency connectivity into high frequency bands8. This approach is particularly powerful when confounding signals and their harmonics occupy wide frequency bands that are not stationary during the scan.In the current study, we introduce an extension of spectrally and temporally segmented regression that implements iterative regression of spectral residuals at the interfaces between frequency bands to further reduce in artifactual high-frequency connectivity. The approach allows to measure high frequency connectivity during hypo- and hypercapnic states, which has been shown to alter BOLD contrast9.

METHODS

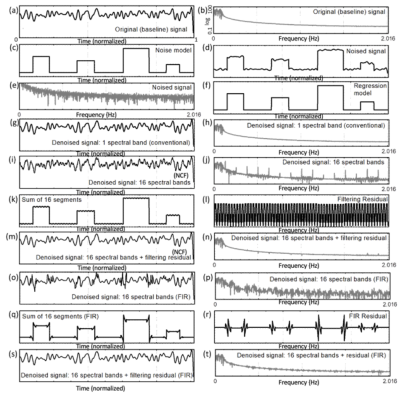

Resting-state fMRI data (eyes open) was acquired in 13 healthy subjects on a 3T scanner equipped with 32-channel array coil using multi-slab echo-volumar-imaging (MS-EVI) (TR/TE: 246/30 ms, slice partial Fourier: 6/8, no. slabs/slices: 4/29, voxel size: 4mm isotropic, scan time: 4min35s) and multi-band EPI (TR/TE:205/30ms, multi-band acceleration factor: 8, no. slices 24, voxel size: 4mm isotropic, scan time: 10min21s). Scans during normocapnic (mean: 40 mm Hg), hypocapnic (mean: 25 mm Hg) and hypercapnic (mean: 55 mm Hg) condition were acquired in randomized order.Spectrally segmented regression relies on employing either a non-causal filter or a FIR filter to split the regression vector in the spectral domain into k-bands. Following spectral segmentation, the data is segmented in time into n temporal segments and regression is performed in each temporal segments using the spectrally segmented regressors corresponding to the temporal segment. Discrepancies between the sum of the spectral segments and the original regressor arise at the interfaces of spectral segments, in particular for an FIR filter (Fig. 1). The residual from filtering can be obtained by regressing the original whole-band regressor from the sum of the spectral bands. This residual is then included as a regression vector in the regression process. Regression performance was characterized as function of the number of spectral segments (k) for different sampling rates and number of time points. Rigid-body motion correction was performed using the TurboFIRE software10. Spectrally and temporally segmented regression was performed using a custom MATLAB tool (TurboFilt). Regression vectors for motion regression were obtained by spectrally segmenting the 6 motion parameters into 12 spectral segments each. Spatially averaged physiological noise within CSF and white matter masks was manually labeled in the frequency domain in each of the time segments and spatial masks for each of the labeled frequency bands were created based on a power-spectral integral threshold relative to a labeled non-physiological noise frequency range (3:1) to spatially average physiological noise signals and create a set of physiological noise regressors for each frequency band and temporal segment. Sliding-window (9.4 s) correlation analysis with meta-statistics and 8 mm isotropic spatial smoothing was performed using TurboFIRE software11. Unilateral seed were selected in sensorimotor (SMN) cortex.

RESULTS

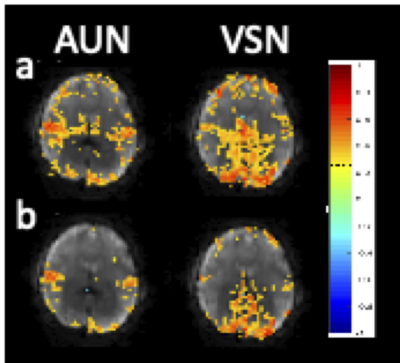

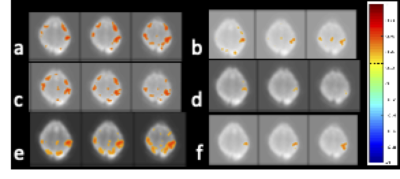

Computer simulations were performed to compare the regression of confounding signals with conventional regression under conditions of (a) no errors and (b) frequency-dependent errors in the regression model. In Fig. 1, box cars are introduced into a baseline signal as confounds. It is assumed that the regression model is identical to the injected noise. In this case, conventional regression is exact. Spectrally and temporally segmented regression with inclusion of residual regression shows comparable regression performance with negligible differences in residuals. Regression of residuals is shown to be particularly important for the case of FIR bandpass filters. Under conditions of frequency-dependent errors in the regression model, conventional regression fails and spectrally and temporally segmented regression recovers the original signal (Fig.2). Simulations showed that regression performance for a 2 Hz bandwidth, which corresponds to our experimental conditions was optimal for 10-12 bands. In vivo, spectrally and temporally segmented regression significantly reduced motion artifacts compared with conventional regression (Fig.3). High-frequency connectivity was detected with high sensitivity and co-localized with traditional low-frequency connectivity. Bilateral motor connectivity under conditions of hypocapnia was markedly reduced compared with normocapnic condition (Fig.4), consistent previous studies9.DISCUSSION

The effectiveness of regression in the low frequency bands substantially improves with increasing number of spectral segments as vectors from different spectral bands are given different weights during regression which mitigates uncertainties in regression vector at higher frequencies. However, the risk of overfitting increases with the number of regression vectors and decreasing sampling rate and number of time points. We are therefore exploring analytical models for determining the optimal number of spectral segments.CONCLUSIONS

A novel approach for the suppression of motion and physiological noise in high-frequency resting-state fMRI is proposed and extended to include regression of filtering residuals. The approach, consistent with the recommendations in7, results in improved suppression of noise and avoids the introduction of spurious components into higher frequencies when sufficient number of regression vectors is used.Acknowledgements

Supported by 1R21EB022803-01. We gratefully acknowledge Essa Yacoub, Sudhir Ramanna and Steen Moeller for their contributions to the development of multi-slab echo-volumar imaging.References

[1] C. Chang and G. H. Glover, "Time-frequency dynamics of resting-state brain connectivity measured with fMRI," Neuroimage, vol. 50, pp. 81-98, Mar 2010, 2827259.

[2] V. Kiviniemi, T. Vire, J. Remes, A. Abou elseoud, T. Starck, O. Tervonen, and J. Nikkinen, "A Sliding Time-Window ICA Reveals Spatial Variability of the Default Mode Network in Time," Brain Connectivity, vol. 1, pp. 339-347, 2011.

[3] U. Sakoglu, G. D. Pearlson, K. A. Kiehl, Y. Wang, A. Michael, and V. D. Calhoun, "A Method for Evaluating Dynamic Functional Network Connectivity and Task-Modulation: Application to Schizophrenia," MAGMA, vol. 23, pp. 351-366, 2010, PMC pending #180300.

[4] H. L. Lee, B. Zahneisen, T. Hugger, P. LeVan, and J. Hennig, "Tracking dynamic resting-state networks at higher frequencies using MR-encephalography," Neuroimage, vol. 65, pp. 216-222, Jan 15 2013.

[5] V. K. Trapp C, Posse S., , "Confound Suppression in Resting State fMRI using Sliding Windows and Running Mean," in Proc. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM), Honolulu, HI, 2017, p. 5344.

[6] J. E. Chen, H. Jahanian, and G. H. Glover, "Nuisance Regression of High-Frequency Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Data: Denoising Can Be Noisy," Brain Connect, vol. 7, pp. 13-24, Feb 2017, PMC5312601.

[7] J. E. Chen, J. R. Polimeni, S. Bollmann, and G. H. Glover, "On the analysis of rapidly sampled fMRI data," Neuroimage, vol. 188, pp. 807-820, Mar 2019.

[8] K. Talaat, Sa De La Rocque Guimaraes, B., Posse, S, "Spectrally segmented regression of physiological noise and motion in high-bandwidth resting-state fMRI," in International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM), Virtual Conference, 2021, p. 2690.

[9] L. J. Kemna and S. Posse, "Effect of respiratory CO(2) changes on the temporal dynamics of the hemodynamic response in functional MR imaging," Neuroimage, vol. 14, pp. 642-649, Sep 2001.

[10] S. Posse, F. Binkofski, F. Schneider, D. Gembris, W. Frings, U. Habel, J. B. Salloum, K. Mathiak, S. Wiese, V. Kiselev, T. Graf, B. Elghahwagi, M. L. Grosse-Ruyken, and T. Eickermann, "A new approach to measure single-event related brain activity using real-time fMRI: Feasibility of sensory, motor, and higher cognitive tasks," Human Brain Mapping, vol. 12, pp. 25-41, Jan 2001.

[11] S. Posse, E. Ackley, R. Mutihac, T. Zhang, R. Hummatov, M. Akhtari, M. Chohan, B. Fisch, and H. Yonas, "High-speed real-time resting-state FMRI using multi-slab echo-volumar imaging," Front Hum Neurosci, vol. 7, p. 479, 2013, 3752525.

Figures