2530

Tumor Tissue Segmentation for Seed-based Mapping of Peritumoral Resting-State Connectivity in Patients with Glioblastomas1Lovelace Medical System, Albuquerque, NM, United States, 2University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States, 3Neurinsight LLC, Albuquerque, NM, United States, 4Neurology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States, 5Physics and Astronomy, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, fMRI (resting state)

In this study, we developed a model-free seed selection approach using deep learning-based tumor tissue segmentation in combination with iterative subject-specific seed-optimization which improves the specificity of peri-tumoral seed selection. The methodology automates seed placement in the vicinity of the tumor in the zone that is at risk during surgical resection without relying on neurofunctional brain atlases. Evaluation of cortical eloquence in different tumor subregions, such as edematous and infiltrative regions was feasible using a single MRI contrast. This computationally efficient approach was integrated into a real-time resting-state fMRI analysis pipeline to characterize peri-tumoral connectivity in patients with glioblastomas.INTRODUCTION

Presurgical mapping is an emerging adjunct to task-based fMRI for mapping functional connectivity1-17. Seed-based connectivity (SBC) is the most widely used approach for clinical studies, since it provides high sensitivity and straightforward interpretation of connectivity in single patients18,19. However, functional neuroanatomy changes in the vicinity of tumors can make seed selection in the vicinity of the tumor unreliable, despite considerable progress with classifier-based brain parcellation and neural network-based training20-24.In this study, we developed a model-free seed selection approach using deep learning-based tumor tissue segmentation in combination with iterative subject-specific seed-optimization which improves the specificity of peri-tumoral seed selection. The methodology automates seed placement in the vicinity of the tumor in the zone that is at risk during surgical resection without relying on neurofunctional brain atlases. This approach was integrated into a real-time rsfMRI analysis pipeline to characterize peri-tumoral connectivity in patients with glioblastomas.

METHODS

RsfMRI (eyes open, 5-10min) and tfMRI (3min per task) data were acquired in 6 patients (4M,2F, 46-67y) with glioblastomas using a 3T scanner equipped with 32-channel head coil25,26. Informed written consent was obtained. Tasks were tailored to tumor location: motor (finger-tapping/fist-clenching), visual (eyes open/close), auditory (listening to syllables) and language (word/verb generation). Real-time fMRI was performed using single and multi-echo MB-EPI (TR/TE: 400/35ms or TR/TE1/TE2: 400/15/41ms, multiband-acceleration:8, flip-angle:30o, voxel-size:(3mm)3, 40slices). Real-time tfMRI and rsfMRI SBC analyses of major RSNs were performed using the TurboFIRE tool27-29. RSNs were mapped using unilateral Brodmann area (BA) based seed regions (sensorimotor network (SMN): BA01-03, language networks (LAN): BA44,45 (Broca’s) and BA22,39,40 (Wernicke’s).Peritumoral connectivity was measured offline by integrating deep learning-based tumor tissue segmentation into TurboFIRE. A 3-dimensional U-net convolutional neural network (CNN) based on the self-adaptive and benchmark-leading nnUNet30 method was used for glioma tumor subregion tissue prediction of the BraTS 2021 database31. The network is based on a 128x128x128 1-mm3 isotropic voxel patch with sliding window inference. Data augmentation during both training and testing was used with a 6-layer UNet containing 31 million trainable weights. Training and cross-validation were performed using k-fold cross validation (k=5). Training and predictions employed an NVIDIA 3090 GPU. A client-server Representational State Transfer (REST) HTTP interface for the trained CNN was integrated into the TurboFIRE real-time fMRI analysis tool to perform segmentation of enhancing tumor, non-enhancing tumor/necrotic core, and edema in FLAIR images. Skull stripping was not required, since peripheral regions have low intensity in fMRI. The tumor tissue mask (viable tumor and necrotic core) was dilated by a fixed distance, an eroded tumor tissue mask was subtracted and the union of peritumoral edema was added to generate a peritumor eloquent tissue area for initial seeding and sliding-window correlation analysis. Subject specific seed-optimization32 was performed using (a) thresholding of the cumulative meta-mean maps and (b) a cluster analysis to locate contiguous above-threshold voxels within the original seed regions to form the seed regions for the subsequent iteration.

RESULTS

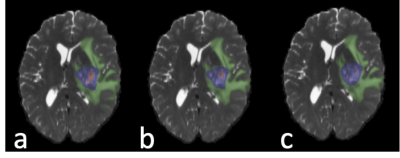

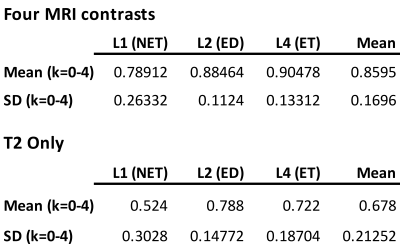

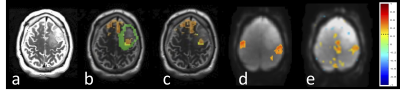

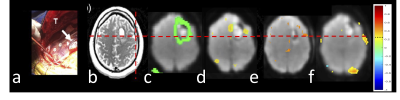

Mean cross-validation Dice similarity scores (Table 1) with 1251 subjects using k-fold training and validation with k=5 employing four MRI contrasts (T1, T1CE, T2, FLAIR) were 0.860±0.170 (Fig.1b) and using only T2 contrast were 0.678±0.213 (Fig.1c). The four contrast DICE scores were similar to the results in33. Subregion DICE scores of edema for T2 only (0.788±0.148) were the closest to those for four MRI contrasts (0.885±0.112). The time for predicting tumor segmentation with four MRI contrasts and using only the T2 MRI was 23 s.Fig.2 shows an example of tissue prediction based seeding in comparison with sensorimotor rsfMRI and motor tfMRI in a patient with a glioblastoma using the dilated tumor tissue mask revealed unanticipated connectivity between an area posterior to the tumor and frontal cortex (Fig.2a) that became spatially more constrained when using iterative seed optimization (Fig.2b). This connectivity was spatially segregated from resting-state motor connectivity (Fig.2c) and task-based motor activation (Fig.2d). Intra-operatively, resection was subtotal at the posterior and anterior margins due to concerns for functional deficits. Peri-tumoral connectivity in another patient with a glioblastoma (Fig.3) was detected lateral and medial to the tumor (Fig.3d), which was in close proximity to Exner’s area that was detected using language resting-state connectivity (Fig.3e) and task-activation (Fig.3f) as shown in our earlier work25.

DISCUSSION

This model-free seeding approach enables systematic assessment of peri-tumoral resting-state connectivity and cortical eloquence in different tumor subregions, such as edematous and infiltrative regions. It has the potential to overcome limitations of machine learning-based seed selection in the vicinity of slow-growing and infiltrative lesions with major changes in functional neuroanatomy. The feasibility of using single-contrast MRI for predicting edematous regions facilitates the integration of automated real-time resting-state fMRI into clinical settings, such as intra-operative fMRI, where time constraints may limit the number of MRI contrasts. Intra-operative ECS of peri-tumoral regions, more detailed task-based mapping and DTI-based tractography will be required to further characterize the neurofunctional correlates of peri-tumoral connectivity.CONCLUSIONS

Seed selection based on tissue prediction in combination with seed optimization provides a novel unbiased approach for probing peri-lesional resting-state fMRI connectivity in patients with brain tumors. The developed tissue prediction based seeding approach has the potential to enhance presurgical assessment of surgical risk in the vicinity of eloquent cortex.Acknowledgements

Supported by NIH grant 1R41NS090691-01A1, 1 R21EB022803-01 and a startup grant by the State of New Mexico Economic Development Department. We gratefully acknowledge our clinical collaborators Drs. Chohan, Jung and Cushnyr and research assistant Jeff Sharpe.References

1. Zhang, D., et al., Preoperative sensorimotor mapping in brain tumor patients using spontaneous fluctuations in neuronal activity imaged with functional magnetic resonance imaging: initial experience. Neurosurgery, 2009. 65(6 Suppl): p. 226-36.

2. Mannfolk, P., et al., Can resting-state functional MRI serve as a complement to task-based mapping of sensorimotor function? A test-retest reliability study in healthy volunteers. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 2011.

3. Lee, M.H., C.D. Smyser, and J.S. Shimony, Resting-State fMRI: A Review of Methods and Clinical Applications. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2012.

4. Liu, H., et al., Task-free presurgical mapping using functional magnetic resonance imaging intrinsic activity. Journal of Neurosurgery, 2009. 111(4): p. 746-54.

5. Castellano, A., et al., Functional MRI for Surgery of Gliomas. Curr Treat Options Neurol, 2017. 19(10): p. 34.

6. Lemee, J.M., et al., Resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging versus task-based activity for language mapping and correlation with perioperative cortical mapping. Brain Behav, 2019. 9(10): p. e01362.

7. Catalino, M.P., et al., Mapping cognitive and emotional networks in neurosurgical patients using resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurg Focus, 2020. 48(2): p. E9.

8. Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. and A. Nieto-Castanon, Conn: a functional connectivity toolbox for correlated and anticorrelated brain networks. Brain Connect, 2012. 2(3): p. 125-41.

9. Huang, H., et al., PreSurgMapp: a MATLAB Toolbox for Presurgical Mapping of Eloquent Functional Areas Based on Task-Related and Resting-State Functional MRI. Neuroinformatics, 2016. 14(4): p. 421-38.

10. Hsu, A.L., et al., IClinfMRI Software for Integrating Functional MRI Techniques in Presurgical Mapping and Clinical Studies. Front Neuroinform, 2018. 12: p. 11.

11. Li, R., et al., Large-scale directional connections among multi resting-state neural networks in human brain: a functional MRI and Bayesian network modeling study. Neuroimage, 2011. 56(3): p. 1035-42.

12. De Luca, M., et al., fMRI resting state networks define distinct modes of long-distance interactions in the human brain. Neuroimage, 2006. 29(4): p. 1359-67.

13. Fox, M.D., et al., The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005. 102(27): p. 9673-8.

14. Raichle, M.E. and A.Z. Snyder, A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage, 2007. 37(4): p. 1083-90; discussion 1097-9.

15. Schopf, V., et al., Group ICA of resting-state data: a comparison. MAGMA, 2010. 23(5-6): p. 317-25.

16. Abou-Elseoud, A., et al., The effect of model order selection in group PICA. Hum Brain Mapp, 2010. 31(8): p. 1207-16.

17. Allen, E.A., et al., A baseline for the multivariate comparison of resting-state networks. Front Syst Neurosci, 2011. 5: p. 2.

18. Van Dijk, K.R., et al., Intrinsic functional connectivity as a tool for human connectomics: theory, properties, and optimization. J Neurophysiol, 2010. 103(1): p. 297-321.

19. Erhardt, E.B., et al., On network derivation, classification, and visualization: a response to Habeck and Moeller. Brain Connect, 2011. 1(2): p. 1-19.

20. Hacker, C.D., et al., Resting state network estimation in individual subjects. Neuroimage, 2013. 82: p. 616-33.

21. Mitchell, T.J., et al., A novel data-driven approach to preoperative mapping of functional cortex using resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery, 2013. 73(6): p. 969-82; discussion 982-3.

22. Leuthardt, E.C., et al., Resting-State Blood Oxygen Level-Dependent Functional MRI: A Paradigm Shift in Preoperative Brain Mapping. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg, 2015. 93(6): p. 427-39.

23. Leuthardt, E.C., et al., Integration of resting state functional MRI into clinical practice - A large single institution experience. PLoS One, 2018. 13(6): p. e0198349.

24. Park, K.Y., et al., Mapping language function with task-based vs. resting-state functional MRI. PLoS One, 2020. 15(7): p. e0236423.

25. Vakamudi, K., et al., Real-time presurgical resting-state fMRI in patients with brain tumors: Quality control and comparison with task-fMRI and intraoperative mapping. Hum Brain Mapp, 2020. 41(3): p. 797-814.

26. Posse, S., Vakamudi, K., Sa De La Rocque Guimaraes, B., Jung, R., Chohan, M., Presurgical Mapping in Brain Tumors with High-Speed Resting-State fMRI: Comparison with Task-fMRI and Intra-Operative Mapping, in Proc. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM). 2020: Virtual Conference, .

27. Posse, S., et al., A new approach to measure single-event related brain activity using real-time fMRI: Feasibility of sensory, motor, and higher cognitive tasks. Human Brain Mapping, 2001. 12(1): p. 25-41.

28. Posse, S., et al., High-speed real-time resting-state FMRI using multi-slab echo-volumar imaging. Front Hum Neurosci, 2013. 7: p. 479.

29. Vakamudi, K., et al., Real-Time Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Using Averaged Sliding Windows with Partial Correlations and Regression of Confounding Signals. Brain Connect, 2020. 10(8): p. 448-463.

30. Isensee, F., et al., nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat Methods, 2021. 18(2): p. 203-211.

31. Menze, B.H., et al., The Multimodal Brain Tumor Image Segmentation Benchmark (BRATS). IEEE Trans Med Imaging, 2015. 34(10): p. 1993-2024.

32. Vakamudi K, A.E., Trapp C, Posse S. Automated Subject-Specific Seed Optimization Method improves Detection of rsfMRI Connectivity. in Proc. International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM). 2015. Toronto, Canada.

33. Zeineldin, R.A., et al., DeepSeg: deep neural network framework for automatic brain tumor segmentation using magnetic resonance FLAIR images. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg, 2020. 15(6): p. 909-920.

Figures